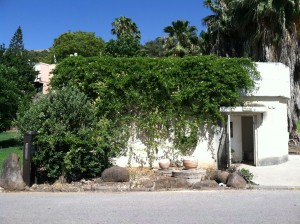

For this post, three images of what’s less often photographed during the excavation. First, the bomb shelter at Kfar Szold that serves as the team’s archival headquarters. Only when I snapped this picture did I recognize the understated loveliness of the building in late spring.

It’s a joy to return to a place that welcomes me like a friend even as it remains new and exciting. Though I admit with a language lover’s remorse that I still can barely mutter “good morning” in Hebrew, and though my role in this dig season is different from that in my last, I arrived at Kibbutz Kfar Szold two weeks ago to find a number of things affectionately familiar: the smell of unwashed pottery in the bomb shelter where the team catalogues its finds; the adrenaline rush, still a little bleary-eyed, of our brief ride to the excavation at Omrit every sunrise; and, of course, Omrit’s temple, which marks our time on site as it glows pale blue, then pink, and finally auburn in the changing daylight.

The details of my digging routine are themselves a mixture of the new and the not so new, and only in part because of my responsibilities this season. As assistant supervisor of a square north of the temple, I share in the charge of teaching first-timers how to go about their tasks. I’m also investigating a part of the site with which I had no experience last year, an area known to have seen significant Byzantine as well as Roman activity. Fortunately the process of excavating falls into basic steps that I remember, at least after clarification from my patient supervisor Edward, and fortunately I have absorbed Omrit’s general history to the point that it can inform my assessment of most parts of the site.

Second, the shelter’s main room, abuzz with activity at the end of the dig day. Archaeology’s least romantic side is on display here in full, posterity-defining force. The artifacts being sorted, measured, and catalogued at the table are destined for the storage boxes in the background.

After about ten days of work, my square-mates and I have unearthed what seems to be the continuation of a wall found last year in a square just south of ours. Our part of the wall curves west, as if to form an apse. We also discovered a straight wall in our square’s south end that extends west from the curved one. In bringing to light these features, I have been struck by an aspect of archaeology that has further to do with the meeting of new and old, of now and then: the desire to locate one piece of evidence rather than another in the struggle to make the physical record of history speak to us today. Entertaining the possibility that the curved wall is part of a surviving Byzantine structure—a church, for instance—the directors of the excavation have encouraged us to look for more indications of this building further west, where we plan to dig next in the hope of following one or both of our walls.

Encouragement of the kind our directors have offered is sound archaeological practice, since time and other limited resources require decisions to be made efficiently and efforts to be concentrated effectively during fieldwork. After all, the director of the excavation at Huqoq, a site the team visited last weekend, is there with the specific aim of finding support for a certain dating of a synagogue type that was characteristic of the ancient Galilee. At the same time that I accept the realities of archaeology, however, I wonder how desire must color the interpretation of what the ground yields. Is this almost inevitable feeling a trap, a hindrance to the understanding of the past? I like to think instead that desire is advantageous, even when an archaeological question can be investigated with extreme patience. Desire’s charge is necessary to the flashes of intuition that, if paired with due rigor, produce what I believe are our best attempts at historical insight. Who knows what flashes of intuition will illuminate this season at Omrit!

Third, team members bringing archival work home to the veranda outside our lodgings at the kibbutz. From left to right, my square supervisor Edward and my square-mates Andrew and Suzette as they label pottery sherds we recovered. Note the red onion bag in which we left the pottery to dry after its post-excavation washing. Prosaic, but effective.