The death on June 11th this year of John Brooks Hoffman, M.D., Williams College Class of 1940, brought to a close a long and enjoyable relationship with one of the Chapin Library’s greatest friends. Brooks loved his country and its history, and collected American documents with a keen eye for quality and importance. Many of these items came to the Chapin Library and the College Archives. We shared his enthusiasm, and he appreciated that his gifts were put frequently into use as part of our educational mission.

With advancing age, and with his beloved wife Jane having passed away, Brooks planned his memorial service in fine detail. I was flattered when he asked me to speak at his service on behalf of Williams College, and accepted only on condition that it not be too soon. He suggested what I should cover, and insisted that I take no more than five minutes, as there would be speakers also on behalf of Blair Academy and the medical profession, and he didn’t want the audience to be bored. I prepared my text and set it aside; happily, I did not need it soon, and was able to speak with Brooks many times before the end.

His service, held in Greenwich, Connecticut on September 12th, included a piano medley of Williams songs (Yard by Yard, The Mountains, ’Neath the Shadow of the Hills, and Our Mother), a hymn written by Washington Gladden, Class of 1859, and a remembrance by Dr. Marc Newberg, Class of 1959, in addition to my remarks which follow.

* * *

In our files at the Chapin Library, the first recorded donation by Dr. and Mrs. J. Brooks Hoffman was a 1796 list of Williams students, presented through the Library to the College Archives. That was in July 1976. There is then a gap in correspondence until January 1980, but by then Brooks and Jane had decided to give to Williams their original manuscript of President Andrew Johnson’s National Thanksgiving Proclamation of 1866. At the same time, Brooks wrote that it was his “intent to leave [to the Chapin Library] on occasion further documents, manuscripts and perhaps autograph letters of prominent people”. He described his collection as only “very modest when one reviews some of the monumental collections” at other institutions. But neither the superb Johnson manuscript nor the hundreds of other items we received from Brooks and Jane over the years are “modest” by any means.

Take, for example, the broadside proclamation of June 12, 1775 signed by General Thomas Gage, received as a Hoffman gift in 1981. Though printed in small type on a small sheet, it has a terrific impact. Gage was appointed Governor of Massachusetts in the hope of quenching fires of rebellion while enforcing unpopular acts of Parliament. In this he was unsuccessful, and his attempt in April 1775 to seize a cache of weapons outside Boston led finally to the outbreak of war. Two months later, Gage’s broadside addressed “the infatuated multitude”, condemning the insurgency at Lexington and Concord and declaring martial law. Even so, he was willing to grant amnesty to all who would lay down their arms – all, that is, except rebel leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams, “whose offences are of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment”. Brooks found this a fascinating fragment of history, and we never tire of showing it to students.

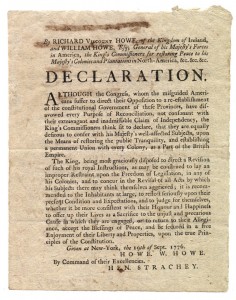

He was also proud of having acquired what we sometimes call the British reply to the Declaration of Independence. This other, almost unknown “declaration” was issued on September 19, 1776 by General Howe and Admiral Howe, the King’s Commissioners for Restoring Peace to His Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations in North America. Admiral Howe had met with a delegation from the Continental Congress, in one last attempt to reconcile the colonies to the crown. Having failed at this, the Howes encouraged the “misguided Americans” who had made an “extravagant and inadmissible” “Claim of Independency” to once again “accept the blessings of peace” under royal authority. This plea was set in type by Loyalist printers, but few copies survive – probably most were torn down as soon as they were put up. The one that Brooks found, and whose historic worth he recognized when others did not, is on permanent display at the Chapin Library along with founding documents of the United States, and its text is read at Williams following that of the American Declaration every July 4th.

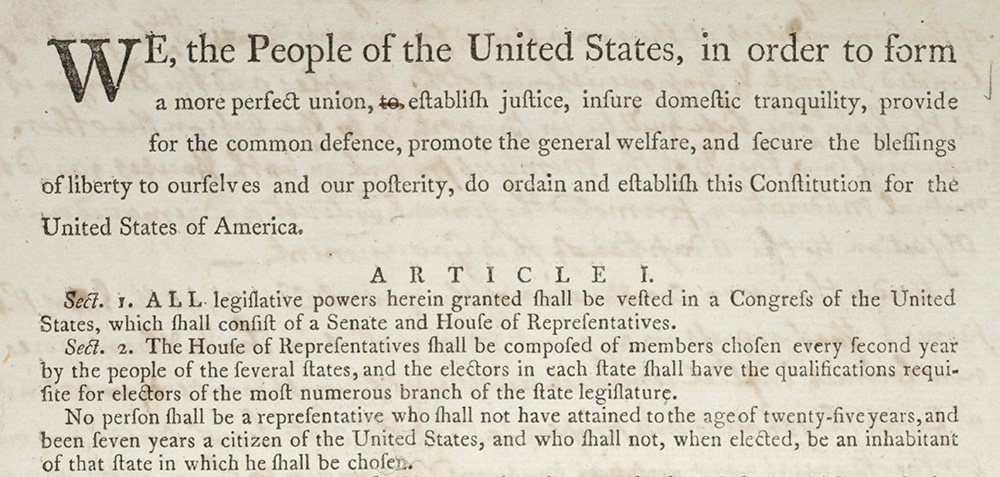

Our copy of the Declaration of Independence, in fact – one of the rare originals printed on July 4, 1776 – is itself partly a Hoffman gift. Brooks was instrumental in helping to raise funds to buy the document in 1983, and himself contributed, along with other loyal Williams alumni, including fellow members of the Class of 1940. A few years later, that gift led to the class presenting to the Chapin Library, on the occasion of their 50th reunion, a substantial fund in support of the Library’s Americana collection. Brooks later established a Chapin fund of his own, which we use to obtain works in his special areas of interest: the American Revolution, the Civil War, the slave trade in America, and the civil rights movement.

When Brooks asked me to speak at his memorial service, he suggested a few things that I might say about him. One was that as an obstetrician and gynecologist, he made a pretty good historian. (That’s verbatim.) By all reports, he was a pretty good obstetrician and gynecologist too. But history was important to him, in particular the history of his country and the use of contemporary manuscripts, books, and documents in its teaching. All of Brooks’s gifts to Williams College illuminate moments in history. They are snapshots of civilization and stones in the foundation of learning. On behalf of everyone at Williams, I am here to say how grateful we all are – how grateful countless students of the future will be – to the generosity of Brooks and Jane Hoffman; and personally, how honored I am to have known Brooks, as a donor and friend, for more than thirty years.

Wayne Hammond, Interim Custodian of the Chapin Library

* * *

An obituary of J. Brooks Hoffman may be read here.

When the Chapin Library’s draft printing of the U.S. Constitution was lent to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in 2014, to be displayed next to the Lincoln Cathedral copy of the Magna Charta, conservators expressed concern over a “fog” within our document’s protective frame of glass and Lexan polycarbonate. Their initial fear was that mold had formed, which might affect the four leaves of the document. Later, it was thought that the Lexan portion of the “sandwich” in which the document was contained had deteriorated due to age. We returned the Constitution to the “shrine” of the Founding Documents of the United States in the Chapin Gallery and spent some months considering the problem.

When the Chapin Library’s draft printing of the U.S. Constitution was lent to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in 2014, to be displayed next to the Lincoln Cathedral copy of the Magna Charta, conservators expressed concern over a “fog” within our document’s protective frame of glass and Lexan polycarbonate. Their initial fear was that mold had formed, which might affect the four leaves of the document. Later, it was thought that the Lexan portion of the “sandwich” in which the document was contained had deteriorated due to age. We returned the Constitution to the “shrine” of the Founding Documents of the United States in the Chapin Gallery and spent some months considering the problem.