Postcard 1: The Wormhole

My final paper explores Sakhalin Koreans and their community as a nowhere through the definition of liminal space. My argument is that Sakhalin Korea is a nowhere built on the liminal space between Korea and Russia, in many aspects: the liminal space in culture, the liminal space in legal citizenship, the liminal space in perception.

Liminal space refers to a space or time in which you shift from one phase to another, “the space between what is and what will happen next” (Neumann, 2022). The sole function of liminal spaces is to provide passage; their nature is transitional by construction. Therefore, my claim that ‘Sakhalin Korea’ is built on a liminal space should be interpreted as saying it is nowhere, since liminal spaces are not meant for staying.

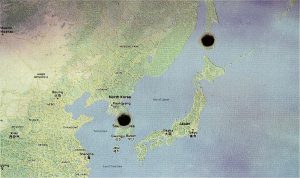

I was considering ways to depict liminal space and came up with the idea of different dimensions. Countries are considered valid ‘somewheres’ under the boundaries drawn in today’s world map, so consider them one dimension—let us say first dimension. Sakhalin Korea, existing as a liminal space between the two countries, cannot be on the same dimension—although it exists on the passage between the two countries, Sakhalin Koreans are not residing somewhere along a line that connects the two countries (which would be the East Sea or part of Japan). That means they are living in a second dimension.

The wormhole theory is perfect for depicting this difference in dimension. A wormhole in theory is a tunnel between two distant points that jumps from one point to the other. Although technically the wormhole theory employs the idea of space-time, if time can be viewed as another dimension, or if, as many scientists postulate, wormholes are projections of a fourth spatial dimension, this is a perfect visual metaphor for my argument (Choi, 2013).

Wormholes are usually explained by drawing two distant dots on paper, warping the paper, and poking the pen through the two dots at the same time. I tried to incorporate this idea into my postcard by using effects on my image of the map to make its texture like paper and creating the illusion of a poked hole through the map to exhibit the wormhole metaphor. One of my dots is on South Korea, not the whole Korea, as 95% of the mobilized Koreans were from provinces in the Southern half of Korea—currently South Korea (Paichadze, 2015).

Sources:

- Picture of map from Google Map

- Copyright free PNGs

Choi, Charles Q. “Spooky Physics Phenomenon May Link Universe’s Wormholes.” Space.com. Space, December 3, 2013. https://www.space.com/23809-quantum-entanglement-links-wormholes.html.

Neumann, Kimberly Dawn. “Liminal Space: What Is It and How Does It Affect Your Mental Health?” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, November 28, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/what-is-liminal-space/.

Paichadze, Svetlana, Philip A. Seaton, and Igor R. Saveliev. “Borders, Borderlands and Migration in Sakhalin and the Priamur Region: A Comparative Study.” In Voices from the Shifting Russo-Japanese Border Karafuto, Sakhalin, 56. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2015.

Postcard 2: Apt. World Mailroom

For this postcard I wanted to use more of the ‘liminal space aesthetic’ as created and used today. As a visual concept, liminal space aesthetic refers to images or visual objects that depict physical liminal spaces, like hallways, waiting rooms, parking lots, rest stops. The rationale for the enthusiasm of the public for the liminal space aesthetic is the eeriness, apprehension or nostalgia that can be felt from seeing such places outside of their designed context. Examples would be images picturing only empty hospital corridors; they are usually not the focus of attention and are filled with people (because of their function as passageways).

In this postcard I imagined the world being one apartment called Apt. World. Each country is a room, and employing the liminal space aesthetic, Sakhalin Koreans living in their liminal space can be pictured to be living in the hallway that connects Russia and South Korea.

I used the idea of red stamps depicting valid / invalid address to show that nowheres usually do not get international recognition as valid somewheres, because they don’t fit into the current world map (which would be room layouts, in this mailroom setting).

Sources

- Copyright free PNGs

Postcard 3: The Matrix for Sakhalin Koreans

Out of the various liminalities discussed in my paper, this postcard focuses on the liminal space in perception. The generation of Sakhalin Koreans who long for South Korea tend to be second or third generations, raised by parents who terribly missed their home country and went to great lengths to preserve Korean cultures and practices. To them, Korea is almost a personification of their parents. It is where their parents told them ‘homeland’ is; Korean culture was the basis for the distinct Sakhalin Korean culture they developed. They have inevitably idolized and personified South Korea because the whole culture of Sakhalin Korea was based on the sentiment of longing.

However, Korea now is not the Korea that was when their parents were forced to leave the country. Korea has evolved so much in such a short period of time and not many traces of Korea in the 1900s can be seen. This is why most Sakhalin Koreans who have actually returned do not adjust well in Korea and stick to the community of returned Sakhalin Koreans, where familiar culture is practiced and communicated (Cho, 2014)

Thus these people are stuck between a perceptional liminal space, between ideal imagination and reality. Recently Korean laws have changed and allow select eligible Sakhalin Koreans to return, and they are caught in a Matrix-like, blue-pill-red-pill situation. They have spent their life dreaming of returning, expecting that their homeland will embrace them, and that they will fit right in. However, they also know going to Korea will likely shatter their idealized vision of their ‘homeland’, the emotional basis of the Sakhalin Korean sentiment and culture. The former (returning) is analogous to the red pill in that they will wake up to face the reality that homeland doesn’t exist anymore. The latter (staying) is analogous to the blue pill in that they’ll stay in Sakhalin until they die, longing for Korea, but not having to face the reality.

On the left-hand side, which is the blue pill side, I’ve created a collage with pictures of first-generation Sakhalin Koreans as representative of the parent generation, traditional Korean buildings, and carrot kimchi (symbol of distinct Sakhalin Korean culture—they couldn’t get napa cabbage in Sakhalin, which is what traditional kimchi is made of). On the right-hand side, which is the red pill side, I’ve included pictures of things I think best describe current South Korea: its tech-savviness through the Samsung logo and Galaxy phone, its cultural influence through BTS and Squid Game, its economic development through the picture of the completely transformed, skyscraper-filled landscape.

Sources

- Copyright free PNGs

Cho, Woo Jeong. “The Homeland on the Move: Diasporic Practices of Belonging in Sakhalin Korean Repatriation.” PhD Dissertation, Indiana University Bloomington, 2014.

Druzhinina, D. “Sakhalin Koreans: The Story of a People without a Country Trying to Make a Home.” Haps Magazine, November 3, 2013. https://www.hapskorea.com/sakhalin-koreans-story-people-without-country-trying-make-home/.

Underwood, William. “Hundreds of Ethnic Koreans from Sakhalin to Return Home: A Colonial Legacy.” The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus 5, no. 9 (September 3, 2007).