Postcard 1: Tipos del País

(Click on entries for more detail)

| The Native Woman of Manila | The Woman of Mixed Native and Spanish Heritage | The Spanish Woman |

| The Provincial Native Woman | The Moro (Muslim) Woman | The Old Native Woman |

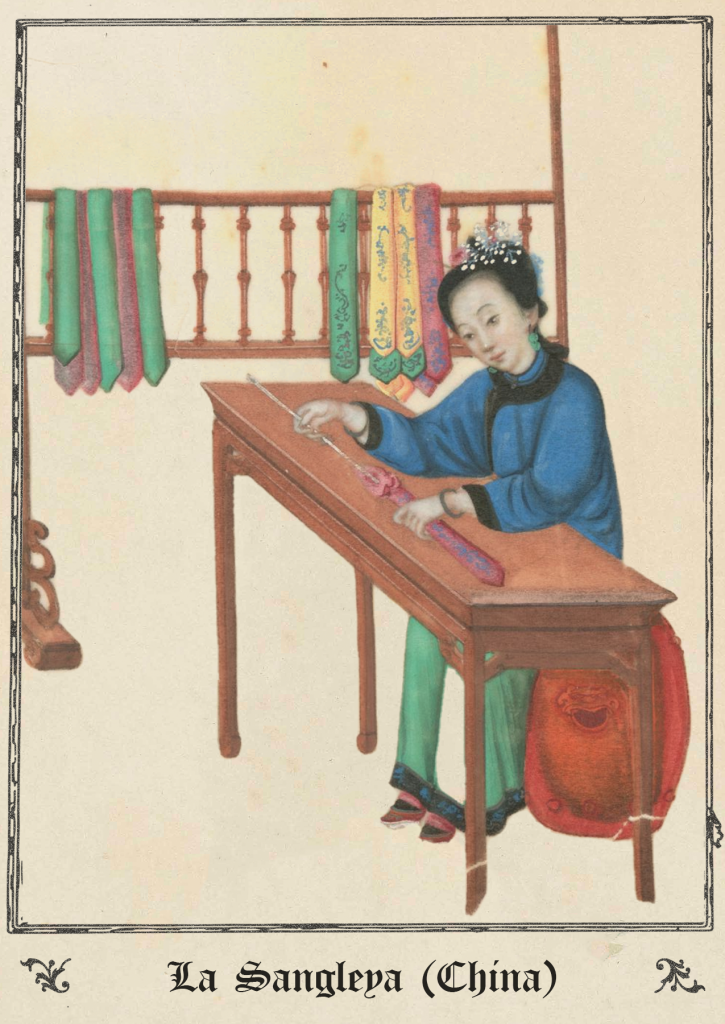

| The Native Saleswoman of the Field | The Woman of Mixed Native and Sangley (Hokkien Chinese) Heritage | The Sangley (Hokkien Chinese) Woman |

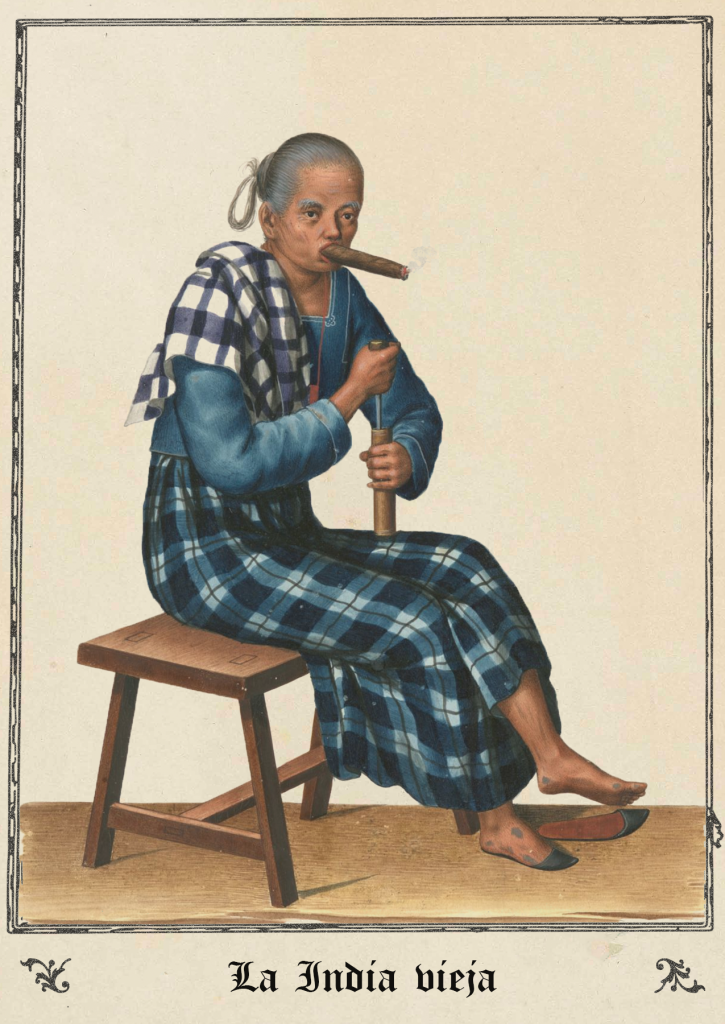

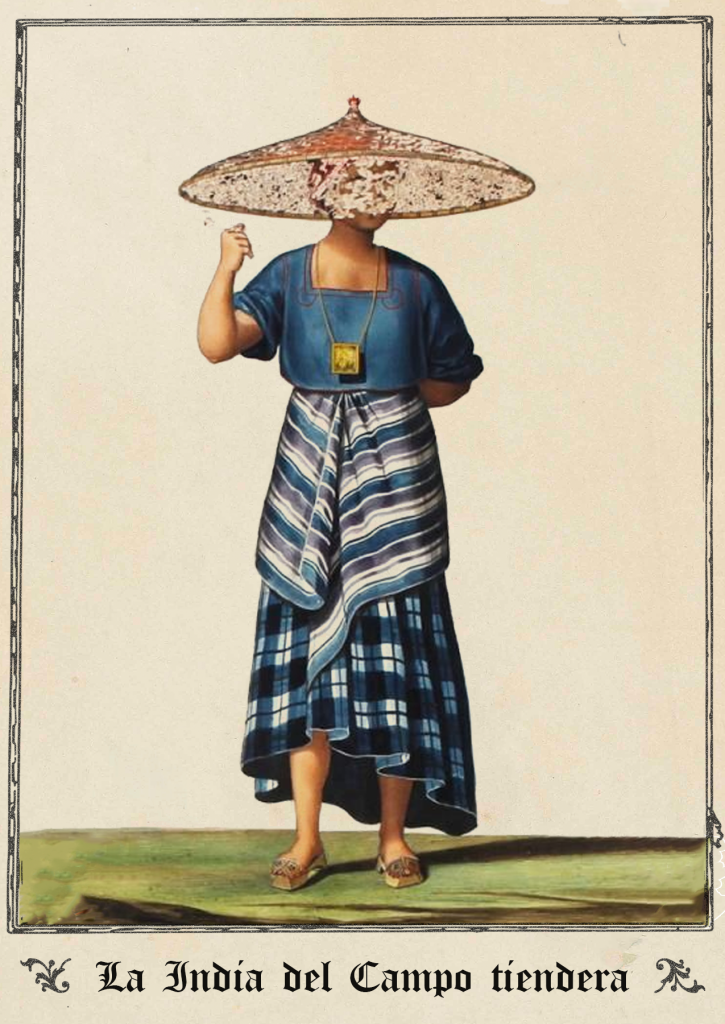

The natively developed Philippine artform of tipos del país (lit. types of the land) relentlessly cataloged as many “types” of Philippine costume and phenotype as possible (Clark 2014, 74). Example illustrations from the artform’s peak in the 1840s came printed with obsessively specific designations of “Chino” (Chinese), “Indio” (lit. Indian, referring to “native”), “Mestizo de Español” (lit. Mixed with Spanish), and “Mestizo de Sangley” (lit. Mixed with Sangley [Hokkien Chinese]) and the occasional indigenous “Igorot” (an exonym for Ifugao peoples).

Tipos most often came in the form of literal postcards—available as souvenirs of the “exotic” colony—or as illustrations within travel books, where they represented the “types” of people able to be encountered in the Philippines by (presumably Hispanic) travelers.

The illustrations featured are from native 19th century artists José Honorato Lozano (La Mestiza Sangley y China) and Justiniano Asunción (all other illustrations), who are considered to have been two of the most prominent artists within the genre. Their work within the genre, together with that of contemporary Damián Domingo, demonstrated an attempt at defining what exact “types” of people “belonged” within the borders of a slowly emerging “Filipino” nationality. These artists, notably, all originated from Tagalophone and predominantly ethnically Tagalog areas.

Despite Moro peoples existing within the prescribed boundaries of the Spanish colony, and (caricatured) Moros featuring in contemporary popular culture (as in the Moro-moro dance), only one explicitly labeled set of Moro tipos has ever been publicly archived. The “Moro[s] de Joló” tipos were produced by Filipino illustrator Félix Martínez in 1887, decades after the artform’s peak, apparently only for the use of contemporary Spanish anthropologists (Roces 2021).

Other non-Christian (but also non-Muslim) groups would contrastingly still appear in travel books such as Lozano’s Spanish-language Vistas de las yslas Filipinas y trages de sus abitantes [sic], even if Christian Filipino illustrators would depict them incredibly disparagingly.

Tipos del pais have seen a massive resurgence in popularity since the 2010s— for many contemporary consumers, they have become a “delicious affirmation of a single version of a nation’s narrative of becoming.” (Roces 2021). Yet Moros—“Muslim Filipinos”—are left out.

This postcard—or rather, set of postcards—asks the question of what it means to be excluded from an artform meant to depict every type of person belonging to the prototypical “nation.” If Moros were deemed outside of the (Tagalog-centric) “Filipino” nation for centuries, what does it mean for the postwar Philippine state to claim them as definitively anti-colonial “Filipinos”?

Sources:

Clark, John, Michelle Antoinette, and Caroline Turner. “The Worlding of the Asian Modern.” In Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions: Connectivities and World-Making, 67–88. ANU Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13wwv81.7.

Lozano, Jose Honorato. Vistas de las yslas Filipinas y trages de sus abitantes, 1847. Manila, Philippines.

Roces, Marian. “Costumes, colleciónes del trajes, costumbres, costumbrista.” In Mapping Philippine Material Culture, 2021. https://philippinestudies.uk/mapping/tours/show/21

Postcard 2: Morolands

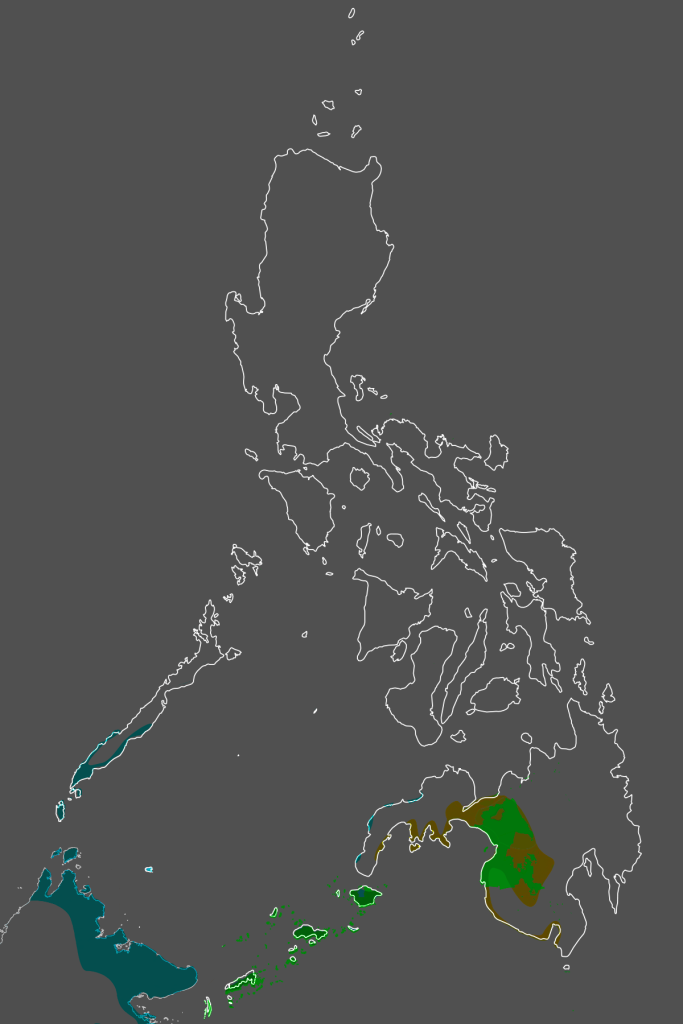

The separatist concept of Bangsamoro has emerged as the Philippine autonomous region of Bangsamoro. The area’s current map—indicated in green—collectivizes several Muslim-majority provinces, vaguely mapping onto the historical spread of Philippine sultanates.

The historical area of sultanates not included under the new divisions of Bangsamoro— the historical reach of the Sultanate of Sulu indicated in blue, the Sultanate of Maguindanao indicated in yellow—sometimes breached what are now modern international boundaries, extending into the contemporary territory of the neighboring country of Malaysia.

I’ve grayed out the remainder of the Philippine Islands to match the same tone of external “foreign” Malaysia—while the physical boundaries of territories still remain, the distinct colored delineation of the nation-state has given way to a perceptibly ambiguous grouping of islands.

Postcard 3: Together and Apart

The immediate predecessor administrative region to Bangsamoro—the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (abbreviated as ARMM)—was recognized by the federal Philippine state more as a distinctive grouping of provinces than a separate national identity. The Manila-directed Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Act No. 12 (1992), which had been applied to ARMM, contained several passages expounding on this interpretation of regional autonomy.

Among other stipulations, the act specified that the ARMM flag was to be always “raised lower than the Philippine flag,” as if to serve as a physical reminder of the federal domination of the Manila government over the borders and constituents of the ARMM.

The Bangsamoro Autonomy Act No.1 (2019), having replaced the MMAA No.12 after its Supreme Court declaration of unconstitutionality, instead dictates that the Bangsamoro flag is to always be “raised alongside the Philippine flag,” implying a greater equality in national identity.

Bangsamoro—while still constitutionally prevented from secession—is allowed to be a nation within the nation-state of the greater Philippines, and to portray itself as having legitimacy.

Sources:

Tawi-Tawi Provincial Government. “AN ACT ADOPTING THE OFFICIAL FLAG OF THE BANGSAMORO AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO.” Facebook post. August 28, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/tawitawigovernment/posts/08282019-office-of-the-chief-minister-barmm-compound-cotabato-city-maguindanao-b/2551989654852316/