How is slavery constructed in the curricular unit about African heritage? How do teachers teach the history of slavery to children? How do children interpret this historical information? To what extent do the lessons they learn about slavery contribute to ameliorate the problem of racism in school?

These questions served as the basis for the ethnographic study conducted in “The lessons of slavery: Discourses of slavery, mestizaje, and blanqueamiento in an elementary school in Puerto Rico.”

Due to time and monetary constraints, I couldn’t conduct an ethnographic study that would really speak to my questions of how African culture could become swept under the rug in Latin@ contexts. In order to compensate for my lack of scope in geographical region, to get to “where it all started,” and to understand the not-so-positive aspects of my Puerto Rican culture, I thought that analyzing this ethnographic study would be ideal.

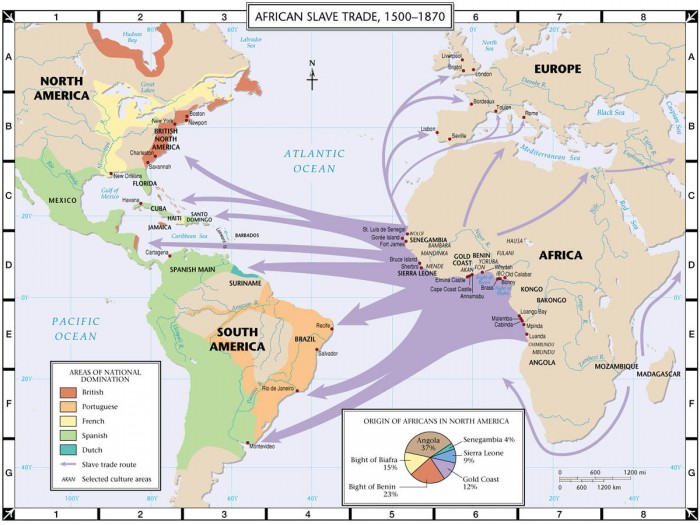

The silencing of slavery and distancing of individuals from blackness arguably begins to manifest in schools. The terms mestizaje, meaning mixed race, and blanqueamiento, whitening, go hand in hand. Since the majority of populations in places like Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic are mixed, it is often believed that race and racism doesn’t exist. Mestizaje in Puerto Rico often comes with the notion that a person is a blend of the Spaniard, the native Taino Indian, and the African. The ethnography argued that understanding social reproduction of national ideologies like mestizaje requires researching the “containment” of slavery. This includes silencing the disconnect between slavery and existing racial disparities.

By actively and thoroughly teaching about the horrors of slavery in Afro-Latin schools, the grounds for the widely celebrated mestizaje in these islands and countries would be shattered. Teaching slavery involves the acknowledgment that one race enslaved, whipped, and tore the families of another race apart for centuries. It means learning that one race killed and displaced millions of another to claim land. It means realizing that mestizaje, racial mixture, includes the rape of enslaved people. These things certainly aren’t worth celebrating. The ethnographic study also found that histories of large free communities of color that existed during slavery and that thrived in these Afro-Latin countries aren’t being acknowledged. The lack of acknowledgment of slavery also allows for prevailing arguments that these Afro-Latin countries and islands are colorblind. It allows people to justify that black people’s socioeconomic failures are individual failures, as opposed to acknowledging a greater racist system that has provided for and molded structural inequality throughout history.

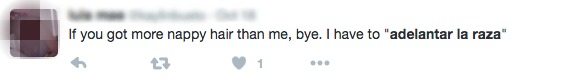

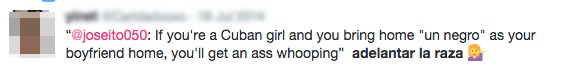

On the other hand, blanqueamiento exists in two major forms. Blanqueamiento, or whitening, supports the belief that Puerto Ricans have “evolved” and have eliminated their African connections. This became huge when Europeans began to migrate to the island around the 19th century for the sole purpose of whitening the population. This ideology also becomes extremely prevalent in everyday life today with the concept of “adelantar la raza,” or pushing the race forward. It is a strategy of marrying people with lighter skin in order to “dilute” African blood, and has been seen in many different Latin@ cultures. This may seem vile to some but previous research on race and racism in Puerto Rico has found that blackness is viewed as “inferior, ugly, dirty, unintelligent, backward, reduced to a primitive hypersexuality (especially in black women), [and] equated with disorder, superstition, servitude, and danger.” This is quite ironic for an island that doesn’t believe in race.

This study turned to an elementary school in Cayey, Puerto Rico (known to have a “whitened view”) to observe and explore state-sponsored representations of slavery and how they could possibly construct and support the ideologies that mestizaje promotes, including the distancing from blackness. It not only involved participant-observation, but also analyzed their textbooks. The third grade is the first year in Puerto Rico where children learn about colonization, slavery, and Puerto Rico’s African heritage. The children were introduced to the three “ethnic roots” of Puerto Ricans: Spaniard, Taino, African. However, these roots were presented in a hierarchy. The Spanish were responsible for language and Catholicism, the Tainos were seen as “noble warriors,” and the Africans were responsible for music, rhythm, and eroticism. With these type of teachings, it becomes clear why some Puerto Ricans may not want to identify with blackness, something displayed as mystical and erotic and is difficult to relate to based on what is being taught in the curriculum. The census of 2000 showed that 8% of the Puerto Rican population identified as black, while 80% identified as white. In places like Cayey however, 3.9% of people identified themselves as black, while 88.2%, almost 9 out of every 10 people, identified themselves as white.

With this portrayal in mind, it is natural to wonder how the school portrays slavery. Based on the ideologies that prevail in Puerto Rico, slavery, solely based on racial inequality, has to coincide with beliefs of racial democracy. There was concrete evidence of what the study calls “maneuvers of silence.” Textbooks depict slavery as an institution that was inconsequential. In the most recent textbook that the students were using, it was only mentioned in one paragraph that highlighted key abolitionists. The lessons of these teachings is to encourage students to “not reject anyone because their skin color is different from ours.” Since Africans were the ones who were “rejected” in the system of slavery, it is assumed that the “different” skin color is black and “ours” is not.

Lessons also involved asking students:

What are your opinions about the black race? How would you treat a black student that came to the classroom?

These questions imply that no one in the classroom is or is expected to identify as being black. One student replied:

I know that I can’t say that I don’t like the Indian, Spaniard, or black person becauseI know I have something from those three races.

Students were acknowledging the mixture, and totally denying any reason for racism. However, there is a difference between acknowledging African heritage and embracing it.

Another one of these exercises brought to light that there were children who identified as black in the class. They shared stories of rejection from not only their classmates, but from their families.

One child said ‘my grandfather is always calling me prieto (synonymous with black) and I don’t like it! They talked about getting called names like ‘black coffee,’ ‘black faggot,’ ‘Coca-cola,’ or ‘black African.’ One boy added ‘they are always calling me burnt pork chop.’

Slavery is rarely depicted in textbooks, but when it is, it was explained as a valid system that was not practiced correctly. The textbook doesn’t find fault in the system, but in individual outliers that strayed from humanistic values. The devastating effect that slavery has had on the lives of black people for centuries then seems minuscule and illegitimate. While shaming the outliers, the book also makes sure to highlight white abolitionists who performed heroic deeds by buying slaves in order to grant them their freedom. Any time a black person is mentioned they are nameless and never referred to as puertorriqueños, which would assert their belonging on the island.

The lessons of slavery that were observed in this study show that black people are reduced to being slave and foreign. How could an island embrace Afro-Latin@ when it can’t even teach about the truths of the “Afro”?

GODREAU_et_al-2008-American_Ethnologist

Very inspired ! Bravo My friend! this is the best post I’ve ever read, may I know you better?

really a great job his friend ,, and a nice article …