I do think the veracity of Ché’s claim is fairly high. No one who is sane just seeks out violence. However, in order to get the thing that they want—in this case, a revolutionary moment—violence may be the only means in which to achieve that goal; nonetheless, if it proves to be possible to reach the same end without putting people in danger then that will always be the route most preferred. Whether a movement is a violent one or not hinges mainly on the reactionary forces—those who are attempting to remain in power. Once they deem it necessary to use violence in order to suppress activism, a whole new can of worms has been opened.

Like an animal backed into a corner, the revolutionary coalition will be free to fire back—usually harder and with much more reckless abandon. As Goodwin would point out, this reversion to violence by the hegemonic group could also prove to be detrimental by the simple fact that the perceived injustice done upon the revolutionary forces will bolster more support from the masses. In this way, violence would serve not to repress the troublesome rebels, but actually to empower them and give them even more numbers.

Interestingly enough, the revolutionary leaders need the masses just as much—if not more— than the masses need them. Without the prospect of mobilization, or simply the means to stage any sort of effective demonstration, an entire movement can go up in flames. Having said that, it is imperative that once the masses are acquired, they be led stage by stage in order to ensure that the correct steps are being taken to give the group the best chance at a favorable result. This can be a slippery slope, as the responsibility (and power) that comes with leading such a large group can lead to bigheadedness and even an eventual tyrannical pursuit of authority. This is what Ché, Allende, and even Baader—any movement leader really—must contend with and learn to balance.

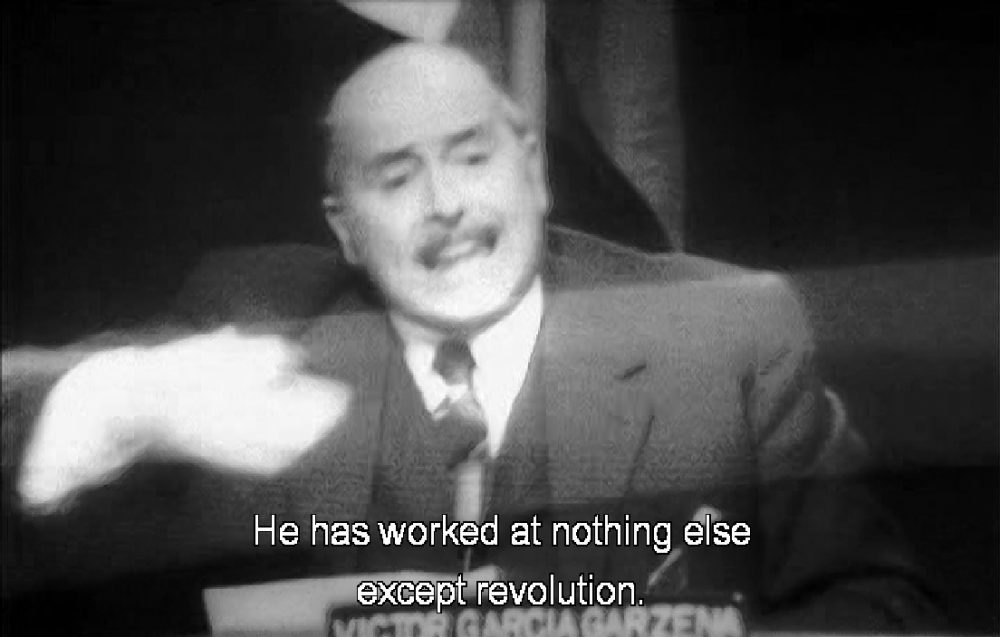

The way you and others speak of revolutionary forces as separate from, but needing the masses’ support brings up an interesting point. Many of the revolutionary movements we have been studying have been left-wing, proletariat-oriented movements that seek to empower the proletariat to rise up against the current hegemonic order and to embark on radical socioeconomic redistribution paths (i.e. wage hikes, increase in human and cultural capital among the lower classes, nationalization efforts, etc.). Yet, these movements largely do not draw (at least initially) their leaders from among the lowest classes, but rather have an air of elitism to them. Take, for example, the Baader-Meinhof Gang–the leaders were largely drawn from the middle-class and several (including Meinhof herself) were college-educated, not exactly proletariats. In Chile, Allende was a career politican and a doctor, who was very much embedded in Chile’s elite networks, yet then sought to promote the interests of the lower classes. Lenin of the Bolsheviks was born to a wealthy middle-class family and attended university (though was kicked out for his protests against the tsarist government before finishing). The list goes on. The essential point, then, is that all of these pro-proletariat/worker/lower class movements were led, and in many cases started by, members from each society’s elite circles, all of whom had access to the existing status quo’s elite institutions of capital–human, cultural, financial, etc. Why then did they seek to incite revolution, or at the least, radical transformative change when they themselves had access to much of the elite resources? Did these revolutionary movements truly seek to bring about change for the benefit of the proletariat, or were there motivations much more nefariously self-interested, in that such “elitist” leaders saw the political opportunity to generate support from the masses through their pro-proletariat stance as a way to gain total political power, capture the state’s resources, and thereby benefit themselves and their inner circle? That is, did mass-oriented ideology serve as a pretext to change the rules of the game (i.e. initiate regime change in the political science meaning of the term) for their own benefits? In any case, there seems to be a contradiction between a movement that is purportedly for and led by the masses, but in reality is fomented, initiated, and led by members of the status quo hegemonic elite.