That Ockeghem composed this Mass to celebrate the Annunciation is confirmed by the illumination Click to see larger version adorning the opening in one of its two sources, the Chigi Codex (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Chigi C VIII 234), a lavish manuscript prepared for Philippe Bouton, Seigneur of Corberon, probably soon after Ockeghem’s death in 1497. Bouton is likely to have had personal contact with Ockeghem on four separate occasions in the 1460s and 1470s, and the Chigi Codex, with its extraordinary concentration of music by Ockeghem, seems intended in part as a memorial to the composer. (Although it has been generally assumed that the scribe of the Chigi Codex was employed by a scriptorium intimately associated with the Burgundian-Hapsburg court, an institution with which Bouton had official ties, the flawed readings of music by the court singer and composer Alexander Agricola contained in this and other codices copied by this scribe have called this assumption into question).

Click to see larger version adorning the opening in one of its two sources, the Chigi Codex (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Chigi C VIII 234), a lavish manuscript prepared for Philippe Bouton, Seigneur of Corberon, probably soon after Ockeghem’s death in 1497. Bouton is likely to have had personal contact with Ockeghem on four separate occasions in the 1460s and 1470s, and the Chigi Codex, with its extraordinary concentration of music by Ockeghem, seems intended in part as a memorial to the composer. (Although it has been generally assumed that the scribe of the Chigi Codex was employed by a scriptorium intimately associated with the Burgundian-Hapsburg court, an institution with which Bouton had official ties, the flawed readings of music by the court singer and composer Alexander Agricola contained in this and other codices copied by this scribe have called this assumption into question).

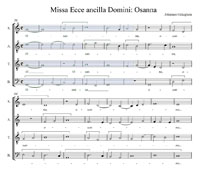

Obrecht’s inclusion of outright quotations from Ockeghem’s Missa Ecce ancilla Domini within his Missa de Sancto Donatiano apparently stem from two separate motivations. Most forthright was the younger composer’s wish to pay homage to one of the most famous composers of the day and to learn by emulating his uniquely suave musical style. More recondite are the ritual and theological implications achieved by referencing a Mass for the Annunciation within a non-Marian Mass setting. Obrecht places the most striking quotation from Ockeghem’s Annunciation Mass at the beginning of the Osanna, whose singing accompanied the Consecration and prepared the Elevation of the Host. It was at this ritual juncture that the substance of the host was transformed into the Body of Christ through the miracle of Transubstantiation, precipitated by the Words of Institution. Medieval theologians noted the potent correspondence between the miracles of Transubstantiation and Incarnation: just as the Incarnation was accomplished without loss of Mary’s virginity, thus making God physically present on earth, so did the Transubstantiation transform the bread without external change in Christ’s Body, making Him physically present at Mass. Thus Obrecht’s quotation of Ockeghem’s Missa Ecce ancilla Domini at the outset of the Osanna functioned as a sonic symbol of Mary and the Incarnation during this critical segment of the ceremony. Indeed, the Lamentation TriptychThe Lamentation triptych (ca. 1475), linked to the Master of the St. Lucy Legend by the pomegranate pattern worn by St. Donatian, bears a connection to Obrecht’s Mass for Saint Donatian in both its original location and its donors… before which the celebrantthe priest officiating at the Eucharist raised the Host would have visually confirmed Mary’s essential role as Christ’s mother for everyone present at Donaes de Moor’s commemorative Mass (as shown at the conclusion of the film clip of the first Osanna found on this site).

Select Bibliography:

For more on Ockeghem’s Mass and its influence on Obrecht, see:

Fitch, Fabrice. Johannes Ockeghem: Masses and Models, Collection Ricercar 2. Paris: Honoré Champion, 1997. See in particular pp. 78-90.

Wegman, Rob C. Born for the Muses: The Life and Masses of Jacob Obrecht. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. See in particular pp. 171-74.

Bloxam, M. Jennifer. “Text and Context: Obrecht’s Missa de Sancto Donatiano in Its Social and Ritual Landscape.” Journal of the Alamire Foundation 3 (2011): 11-36. See in particular pp. 29-30.

For more about the Chigi Codex, see:

Kellman, Herbert, ed. The Treasury of Petrus Alamire: Music and Art in Flemish Court. Manuscripts 1500-1535. Ghent and Amsterdam: Ludion, 1999. See in particular pp. 125-29.

Fitch, Fabrice. “Alamire versus Agricola: The Lie of the Sources.” In The Burgundian-Habsburg Court Complex of Music Manuscripts (1500-1535) and the Workshop of Petrus Alamire, 299-308. Edited by Bruno Bouckaert and Eugeen Schreurs. Yearbook of the Alamire Foundation 5 (2003).