Inception: The Battle of Utopia vs. Dystopia

It is relatively easy to understand why the movie Inception became a box office hit. A quick look at the trailer reveals intense action scenes, visual effects that break the laws of nature, a sci-fi world where you can break into another’s subconscious, and last but most certainly not least – everyone’s favorite – Leonardo DiCaprio. However, if we are to understand what turned Inception from a box office attraction to an instant classic, we are going to need to look past the explosions and visual effects and get to the bottom of what aspects of the movie really resonate with audiences.

To begin, some background on the movie: In the world of Inception, the technology that allows one person to enter the dream of another exists. Cobb, the main character played by Leonardo DiCaprio, specializes in using this technology to extract information from unknowing victims’ through their dreams/subconscious. For Cobb, extracting information is easy. However, inception – theprocess of planting an idea into the subconscious of a victim and letting it grow as if it were their own – is nearly impossible. The plot really gets going when Cobb and a team of his associates are hired to perform inception on the heir to a multi-billion dollar company with the idea that he should dissolve his father’s company. However, all throughout the movie, the job is complicated by Cobb’s history. He spent almost 50 years with his late wife, Mal, living in limbo – a dream world of infinite subconscious that feels more real than reality itself. When they finally returned to the real world, Mal’s blurred perception of reality drove her to commit suicide. She lives on in Cobb’s subconscious, however, so every time Cobb goes into a dream, she is never too far away from sabotaging his mission.

The first thing to notice about this movie: Cobb and his team are pretty normal in the real world. In fact, Cobb is quite vulnerable or even helpless in the real world. He is a fugitive of the law, he cannot gain custody his children, and he doesn’t have the same confidence or James Bond-like skill set that he has on his missions. Cobb’s vulnerability seems to reflect how most of us feel in our day-to-day lives: pretty normal. However, when Cobb enters into a dream, everything changes. He can manipulate matter, change his appearance, ride snowmobiles, use a sniper rifle, kill highly trained men, and even climb down snowy mountains. Therefore, this movie gives audiences the sense that living in a dream is better or, at the very least, more exciting than living in the real world. Offering a utopian version of the world is often a very effective method of engaging viewers in popular culture, and from this initial observation it seems that the mass fascination with Inception could be driven by its utopian features.

But then, the movie moves to complicate this initial observation by presenting the world of dreams as a slippery slope. As Cobb and his team tryto perform inception, the stakes of their mission are raised. Usually, if you die inside of a dream, you wake up. But on this particular mission, sedative drugs are needed to dive deeper into the target’s subconscious. And as a result, if anyone gets killed in a dream while sedated, he or she will fall into limbo and likely get stuck there for good. As a result of this shift, the audience’s utopian perception of dreams is complicated. Now, time spent inside of a dream is presented to the audience as dangerous, not exciting. All the dangers of Cobb’s mission can be traced back to limbo. Limbo challenges the utopian view of the dream world because it presents a deceptive version of a better reality that tricks people into accepting it as a true reality. Ben Aguinaga, in a critical analysis of the film, explains how the deceptive reality of limbo makes it impossible to foster true happiness by recalling that:

“Cobb states, ‘It’s not so bad at first, being gods [in limbo]. The problem is knowing it’s not real. But Mal accepted it; she’d decided to forget that our world wasn’t real.’… Mal succumbs to the attractive ‘reality’ of her dream… she fails to maintain the knowledge that, as the creator of her dream, she created something that was false: something that could not induce true happiness.“ (Aguinaga, 2012)

Therefore, the movie uses limbo to push back against the utopian view of living inside a dream, and instead, presents limbo as a sort of prison. A dystopia where unlimited power and a false sense of reality are the consolation prize for never achieving a state of true happiness that only true reality can provide.

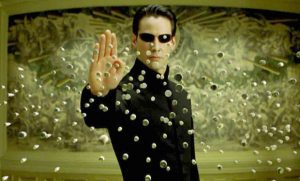

Still, there is a paradox we must address. Despite the fact limbo is the main danger of the movie, it is still the place where the dreamer’s power is at its peak. In limbo, the dreamer has ultimate control over the world around them. This power is put on display by Cobb and Mal’s time in limbo. In their 50-year stay, they used their God-like powers to build a whole city from pure imagination. And the most mind-boggling fact is that Mal chose to live in limbo as if it were her true reality. Somehow, for her, limbo was her utopia! To try to sort this out, let us look to the only other movie that offers a comparable scenario of a dystopian utopia: The Matrix. In The Matrix, the world that humanity lives in is just computer program that is false reality. But in this false reality, the main character, Neo, learns ‘hack’ the program and gain superhuman abilities. A critical analysis of utopia in The Matrix claims that:

“The real source of the fascination with The Matrix is that, despite all appearances, the movie is not a dystopia. Rather, it’s a utopia, a geek paradise… [Neo] gets to pack heat, learn kung fu, wear a black trench coat and sunglasses, and, to top it off, he gets a hot, ass-kicking girlfriend who sports fetish wear. What kind of dystopia is this? … everyone wants to be Neo (or Trinity, or Morpheus) in The Matrix.” (Suellentrop, 2003)

I think direct parallels can be drawn between this analysis of The Matrix and Inception. Sure, in the context of Cobb’s mission, limbo is portrayed as more of a dystopia. But for the audience, how can you call a world where you can build a city without lifting a finger a dystopia? The mere concept of Limbo fascinates viewers, and at the end of the day, I think that anybody would be intrigued to go there and live like a God as Mal chose to do. So despite the dystopian features scattered throughout the movie, there is definitely some form of utopia that persists and attracts the audience as it attracted Mal.

But, in the final seconds of the movie, Inception offers its own way to reconcile the utopian and dystopian aspects of the movie. In the final scene of the movie, Cobb rescues his team from limbo and wakes up. But it is unclear to the audience whether he has woken up to reality, or if he is just in another level of a dream. He gets up and receives his payment for the mission – a valid U.S. passport and immunity from the law – and finally goes to see his kids. In the final shot, he arrives home and spins his spinning top on the kitchen table. Cobb uses this spinning top to figure out whether he is in a dream or reality throughout the movie: If he is in a dream, the top never falls over. If he is in real life, it spins then falls. However, this time, Cobb spins the top, sees his kids, and is so overjoyed that he leaves the top behind to run after them. And then, the movie ends with the audience begging to know whether or not the top fell over. But whether or not the top fell over is not important. What is important about this scene is that Cobb, like his wife, chose to accept the world in front of him as his true reality. Therefore, with this last scene, the movie allows the audience to jump to the conclusion that they had been hoping for throughout the entire movie: That getting lost in the utopia of a dream is not a prison-like dystopia because if the world in front of you appears real to all of the senses, than who is to say that it can’t be your true reality.

So in Inception there are plenty of attractions that draw people to spend that $4.99 to rent it on ‘On Demand.’ But Inception gains its audience’s affection in a similar way that much of popular culture entertains us. By offering an image of a world that is massively better than our own – a utopia. However, Inception earns its own special niche in popular culture by allowing its audience to grapple with their urge to embrace this particular utopia despite its obvious drawbacks. Thus, keeping you on your seat, quite literally, from the opening scene to the closing credits.

Work Cited:

Aguinaga, Ben. “A Critical Analysis of Inception with Respect to the Culture Industry.” Baylor University, May 2012, baylor-ir.tdl.org/baylor-ir/bitstream/handle/2104/8360/Thesis+PDFA.pdf;sequence=1.

Suellentrop, Chris. “The Matrix: Finally, a Dystopia Worth Living in.” Slate Magazine, 1 May 2003, www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/assessment/2003/05/the_matrix.html