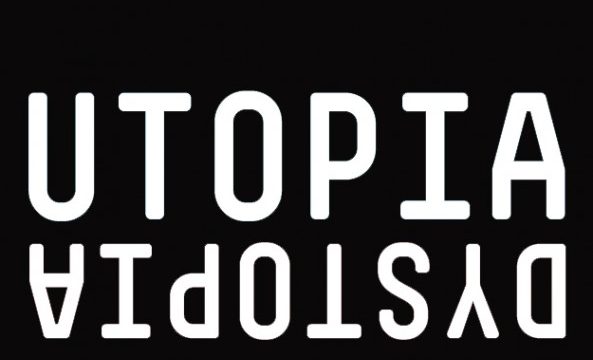

Utopia, the Misnomer for Dystopia in Popular Films

Utopia, the Misnomer for Dystopia in Popular Films

It goes by the name perfection, refinement, and flawlessness. Or utopic, picturesque, and white. It is not blemished, it is not marred, and it is most certainly not black. The entertainment industry, as we know it, is after the complete perception of perfection in every conceivable facet. Beauty-oriented advertisements showcase perfectly set hair, or enviously manicured fingernails. And the quintessential car commercial will feature the 2018 version of the latest Chevrolet concoction, neatly waxed and all four tires seemingly untouched by the ware and tare of daily commute. There is no inclination to purchase Sephora’s cosmetics if the model in their advertisements looks unfiltered. Similarly, Chevrolet is not looking to increase revenue by featuring a used mock-up that looks anything but pristine. In this mode, Hollywood and the entertainment industry has every right to showcase their brightest and best to keep the masses coming back for more. The only caveat being this notion of the brightest and best happen to be Caucasoid, blue-eyed, and blonde or brown haired. The entertainment industry puts its best foot forward in an effort to be utopic; but for those who inhabit the slums of Detroit, Chicago, Baltimore, Washington D.C., or colored skin, is there reprieve from daily melancholia to be submersion into white popular culture, a culture which undermines blackness? The dystopia Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros. and their ilk would misname a utopia virtually silences black voices in film and presents them, when they are represented, in a disparaging light; hence, entertainment is a utopia – for the select few, that is.

Forget the white picket fence, forget paying off the mortgage, and forget that six figure salary; the new and improved American dream is available at the nearest cinema. It is not just your favorite action flick, or your favorite drama, or even your favorite sports biopic, it is any movie that can attract your attention for ninety minutes. Any movie capable of enchanting you just long enough for you to forget that the gas tank is almost on E or the rice might be overcooked or you just missed another loan payment. But this is not just conjecture, adjusted for inflation to 2017 dollars, the highest grossing movie of all time is Gone with the Wind, released in 1939 amid the dispirited years that was the Great Depression (Hutchinson). Americans were residing in shantytowns, sleeping with Hoover blankets, i.e. newspapers, and wearing Hoover leather, i.e. cardboard soled shoes. And still, Gone with the Wind became the highest grossing film to date. This clear desire for escapism seems so dangerously embedded in human normative behavior that a love story set during the American Civil War eclipses the need for adequate food, shelter, and clothing. What money could be spared was used to plunge into the world of Scarlett O’Hara, not aid in escaping the clutches of poverty. There is something appealing about watching a fictional life unfold rather than return to your own, especially when yours is wrought with hardship. Thus, Hollywood is presenting the what if template on a platter. What if these actors were you? What if their lives were yours? And while we may smile and indulge these fantasies, production companies are still profiting, and that overdue loan payment still has not been paid.

Terrorism is no one’s favorite flavor of the month. While America grieved the nightmarish events of the September 11th, 2001 attacks and the U.S. economy plunged into recession, the first installment of the Harry Potter series, released a month and five days after the attacks, grossed $974.8 million. In a similar fashion, released in 1977, Star Wars: Episode IV became the second highest grossing film of all time adjusted for inflation, two years subsequent to the end of the Vietnam War (Hutchinson). The trend is painfully evident, American society, perhaps humans in general, require a reprieve from the ghastly affairs that is real life. In the wake of the aforementioned events, this desire for Fantasy and Sci-Fi flicks, a completely different world, emphasizes society’s escapist desires for something radically unfamiliar. A desire for something that is not steeped in complexities but, instead, is already prepackaged. The intricacies of daily life have filled the human experience with an excessive amount of stimuli that at the end of the day we are ready to consume rather than partake. Ready to consume all the media presented to us on screens as, in most cases, it is broken down in the simplest of forms without a multiplicity of complicated variables. Young Harry trekking through the halls of Hogwarts and overcoming Voldemort seems easier to get behind and stomach than viewing another revised death toll with all its implications.

These films offered hope, inspiration, and utopic ideals. Hollywood, “offers the image of ‘something better’ to escape into, or something we want deeply that our day-to-day lives don’t provide.” However, as moviegoers know, Hogwarts is not particularly utopic, neither is the Millennium Falcon, rather, “utopianism is contained in the feelings it embodies,” (Dyer 273). The very thought of entering into an alternate life seemingly does the trick. The wizarding world is no more utopic than earth, plagued with the same problems of bigotry and the like. But it is different, it is not what we are used to, it propels us into a whole other universe filled with possibilities not found in our own. But even more so, it feeds into traditional ideals of society as consumers; there is a general preference to assume the role of voyeur and watch someone else’s life collapse and reassemble than pick the pieces up of our own. By doing this, the burdens of responsibility and real-world consequences are momentarily wrested from our shoulders. Aiding and abetting in the departure from this malaise are movie moguls who feature generally less than five minutes of dialogue by colored voices.

Why does everything have to be about race? It does not have to be. However, when visual stimuli is the preferred tool of manipulation and utopia inducing desires by the culture industry, “Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation,” (Gerbner and Gross 182). Therefore, when one of the highest grossing films of 2014, The Fault in our Stars, features only 41 seconds of dialogue by a person of color, their existence is virtually nonexistent. When the 2013 film Her, a 126 minute Oscar winning film, features only 46 seconds of dialogue by people of color – who happen to be a letter writer, pizza vendor, and waitress– their importance is being indicated as less than. The entirety of the Harry Potter series is approximately 1,179 minutes, and only 6 of those feature words spoken by a person of color (Madrid). The old adage holds, out of sight out of mind. This idea of ‘symbolic annihilation’ pushed by George Gerbner implies that if these people of color are not constantly popping up in these utopic worlds so often used as an escape, they are somehow unimportant and do not belong there. When these utopic worlds of retreat are expressly white, everything else is assumed to be expressly bad. Eventually, when consumers return to reality they seek out real world representations of their previous cinematic consumption in an attempt to forge a lasting connection. This in turn makes them unconsciously biased against people of color as they are not used to seeing them in a utopic setting. Hence, it may seem somewhat unnatural to associate people of color with positivity, euphoria, and all that is right with the world.

Yet, black films exist. Catalogs of black films featuring black actors are out there. To go even further, there are black-centric genres of films being made for popular consumption. How can this be exclusion and racial bias if these films do exist? Quite simply, if the film industry is charged with presenting utopias to the masses, black films are made in the mode of Chi-Raq. Films wrought with anger, gang violence, and hatred – words not synonymous with utopia. Films which add an extra dimension to ‘symbolic annihilation.’ If removing colored faces from representation is a method of the aforementioned concept, popularizing films featuring blacks in a negative light is even more so. Rather than not even being allowed to think of minorities, you are now being forced to think of them under labels an upstanding law-abiding citizen has no desire to think of. When Chi-Raq hit the theaters in 2015, audiences were bombarded with blaring expletive-laden music, a stream of gang violence, the hypersexualizing of black women, and black-on-black crime. That is certainly no utopia. And one might say the film is just a representation of real life for certain people. While true, it is not the case for all black folk. Chi-Raq is not a standalone either. Training Day features a crooked black cop who is eventually gunned down by Russians, i.e. a historically Aryan race doing their role in eradicating the sinister black plague. Denzel Washington went on to receive an Oscar for Best Male Actor in a Leading Role for his portrayal of Alonzo Harris, the crooked cop gunned down in the end. This was the first time since 1963 this award was handed to a black actor. The fact that it was won by reinforcing a disparaging stereotype of black men as deceitful criminals adds a racial element obvious in itself that points to representation as a method of annihilation. As Harry Potter and Han Solo are the objects of praise and respect, Denzel Washington is picking up Oscars for portraying a criminal, yet movies are to be an escape into utopia. To elaborate, New Jack City, Juice, Paid in Full, Menace II Society, and Boyz n the Hood are all similar to Chi-Raq, marked with black-on-black violence, drug dealing, and glorification of the gun. If these movies, intent upon incorporating blacks into the mainstream culture, constantly showcase black individuals as criminals, is there any surprise black communities are rife with the same struggles they constantly consume? After all, life imitates art.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Chi-Raq is not all the stereotypes it reinforces about blackness, but the events that unfold in the final scenes of the movie. Demetrius Dupree, alias Chi-Raq, is being carried away by the police – cue in all your preconceived notions of incarceration and its relationship with black people. Following his departure is his lover, Lysistrata, walking arm-in-arm with a white priest – cue in all your preconceived notions about whiteness steeped in moral purity. Again, film and mainstream entertainment typically functions as an escape route and a utopia to forget about, if not alleviate, daily woes. Black audiences are then being told to take joy in a film that features black-on-black violence, hyper sexuality, the incarceration of black men, and a white priest as the all-encompassing bringer of truth. I presume the disconnect is evident and the search for a utopia accommodating to black people goes on.

Fingers then point to The Help, or Twelve Years a Slave, or The Butler. All of which showcase wholesome black folk, yet, they feature them in positions of servitude. Which, again, reinforces another stereotype of the black race. This then shifts the black race from miniscule representation, to representations as criminals, to representations in subservient roles. The common thread reappearing is how un-utopic these representations are, if represented at all. There is a tendency for black actors to assume roles involving broken families, positions of servitude, and criminality (Garnett 29). This may imply limitations present in the repertoire of black actors, or these are the roles society wants to see black people in. But more than that, it develops the idea that black people are and can never be born out of something normal. Normal in the sense of being painfully and obviously middle class with no attachments. It proliferates the idea that something is always wrong within black communities. A utopia for the black community is still missing. But ever so often a bone is thrown to people of color. Movies such as Black Panther feature a black superhero that is not bogged down by poverty or other stereotypes. And while black superheroes have existed before in the realms of the Marvel Cinematic Universe or Justice League, these roles are predominantly reserved as sidekicks or team members, rarely the focal point. I will not hypothesize that Black Panther is the first movie that actually represents a utopia conducive to the black community, much more nuanced movie aficionados could probably name a few. However, those few are not the ones being heavily advertised and thrust into the faces of the black community. Instead, it is Chi-Raq and all the violence it implies.

Chi-Raq is not the only representation of black individuals in pop culture, but it is the most common. And violent stereotypical movies like Chi-Raq do have a role to play in representing the reality of numerous impoverished black communities, but it is rather pretentious to proclaim entertainment and its facets are a matter of utopia. If Hollywood is to be in the business of providing happy endings and these films are what are on offer, there are no exaggerations in implying that the current idea of utopia in films is the closest society may get to industry sanctioned genocide of the black race in the post-Civil Rights era. ‘Symbolic annihilation’ is not a myth but a reality. With black figures out of sight, they are essentially out of mind. When they are featured however, it is in episodic rituals of endless violence, drug dealing, servitude, or lending a helping hand. Mainstream pop culture, particularly the film industry, is a vehicle of utopia for society, only, do not include Blacks, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, or any racial group not exhibiting traditional European features in that definition of society.

Works Consulted

“All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation.” Box Office Mojo, IMDB, www.boxofficemojo.com/alltime/adjusted.htm. Accessed 12 Nov. 2017.

Chi-Raq. Dir. Spike Lee. Roadside Attractions, 2015. Film.

Garrett, Melissa Ann. “Contemporary Portrayals of Blacks and Mixed-Blacks in Lead Roles: Confronting Historical Stereotypes of African Americans on the Big Screen.” Order No. 10269723 Iowa State University, 2017. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 14 Nov. 2017.

Gerbner, George, and Larry Gross. “Living with Television: The Violence Profile.” Journal of Communication, vol. 26.2, 1976, pp. 173-194.

Hutchinson, Sean. “Blockbuster Escapism Is Good, Forgetting Its Message Is Bad.” Inverse, Inverse Entertainment, 23 Nov. 2016, www.inverse.com/article/24000-star-wars-rogue-one-trump-escapism. Accessed 13 Nov. 2017.

Madrid, Isis. “Why Is Whiteness the Default in Hollywood?” Arts, Culture & Media, Public Radio International, 10 July 2015, www.pri.org/stories/2015-07-10/why-whiteness-default-hollywood.