Who needs the law?

Apparently the residents of Chelsea, Massachusetts, do not. In 2006, When Chelsea Energy LLC proposed a diesel-fueled “peak” power plant for the majority-hispanic, largely-impoverished community, the people did not sit back and watch as their environment was further attacked. An area resident, Alejo Sanchez, summed up the situation nicely, remarking through an interpreter, “I have enough problems breathing; this is certainly not going to help” (Kelley). Chelsea resident Carolyn Boumilla-Vega expressed her concern, addressing the fact that “the plant would be across the street from my sons’ school and the only public Elementary School in the City,” adding, “it’s such a ludicrous proposal. I hope the state rejects it immediately” (Kelley). Countless others shared similar sentiments. Community leaders in Chelsea, as well as adjacent East Boston and Revere, started a powerful opposition campaign that would go on to kill the project during the environmental review stage of the process, before legal action was necessary. However, many steps were required to reach that point.

This case exemplifies the potential significant impacts community organizing can have. Two non-profit organizations, Chelsea Collaborative’s Chelsea Green Space and Recreation Committee and Alternatives for Community & Environment (ACE), who were “experienced with the MEPA review process…provided technical and legal assistance” (Estrella-Luna). The community was supported by “local officials, including Senator Jarrett Barrios, Representative Eugene O’Flaherty, the Chelsea City Council and the Revere City Council” (Kelley). They even obtained meetings with the Massachusetts Governor, Deval Patrick. As one resident put it, “they always want to put their dirty industries in communities like Chelsea…but Chelsea has already taken enough. I hope Deval Patrick will put his money where his mouth is about environmental justice” (Kelley). The movement was so effective, he never had to.

The community was swift with action, especially the Chelsea City Council. The Boston Globe reported that “in October 2006…the City Council voted 7 to 4 to adopt a resolution…opposing the power plant” (Conti). This was two months before the proponent filed a petition with the state for the project. Even prior to the October resolution, on September 25, 2006, the City Council stated “that it will not approve the tax relief sought by the developer” (Estrella-Luna). The Boston City Council passed a resolution on January 31, 2007 opposing the power plant. Clearly this movement actively implemented what anthropologist Stuart Kirsch calls the “politics of time” (Estrella-Luna).

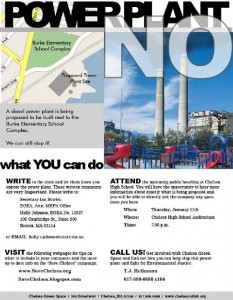

One of the most common forms of action taken against the project was presence at meetings to both become informed and challenge the proponent. In opposing the project, Chelsea residents cited the area’s poor air quality and the proposed plant’s proximity to the Mary C. Burke Elementary School Complex. 80- year old Henry Lea spoke at a Chelsea City Council meeting on January 22, 2007 (Casino). They visited the site and organized workshops to fight the plant. According to participant Neenah Estrella-Luna, “community members of Chelsea Green Space, had met and challenged the proponent in their own meetings as well as at meetings the proponent attended with other non-profit groups in the area” (Estrella-Luna). The citizens maintained an online blog that advertised meetings with the shareholding company, Energy Management, Inc. (EMI), state-sponsored public rallies, and meetings of the City Hall Conservation Committee (“STOP Energy Management Inc.”). These people showed up. They asked questions and made themselves heard.

year old Henry Lea spoke at a Chelsea City Council meeting on January 22, 2007 (Casino). They visited the site and organized workshops to fight the plant. According to participant Neenah Estrella-Luna, “community members of Chelsea Green Space, had met and challenged the proponent in their own meetings as well as at meetings the proponent attended with other non-profit groups in the area” (Estrella-Luna). The citizens maintained an online blog that advertised meetings with the shareholding company, Energy Management, Inc. (EMI), state-sponsored public rallies, and meetings of the City Hall Conservation Committee (“STOP Energy Management Inc.”). These people showed up. They asked questions and made themselves heard.

The community used numerous additional strategies to challenge the proponent. Street protests took place in July, 2006 (Estrella-Luna). Community members disrupted a speech by Jim Gordon, the president of EMI, at the World Oil Conference at Boston University in October, 2006 (Estrella-Luna). The activists partnered with the media to disseminate their message.

Estrella-Luna describes, “the Boston Globe wrote two articles about the project before the EENF was even submitted. An additional five articles were published during the 6 months of review. The Boston Globe editorial board also wrote an editorial arguing against the power plant” (Estrella-Luna). Those opposed to the project also did research and spoke with energy consultants to better educate themselves and the community about the issue. Two petitions, including one in Spanish, received a total of 94 signatures. And finally, over 1,800 postcards were sent to Chelsea City Council requesting action (Estrella-Luna).

Perhaps Chelsea residents’ most impressive and effective strategy was their letter-writing campaign during the state-mandated environmental review process.

Under the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA), the proponent had to submit forms detailing expected environmental impacts for review by the Secretary of Environmental Affairs, Ian Bowles (“Expanded Environmental Notification Form”). This stage occurs even before the permitting process, and Bowles describes at least eleven permits that the company would need to obtain for the project to continue. He explains that “MEPA subject matter jurisdiction exists over virtually all of the potential environmental impacts of the project” because “those aspects of the project…are likely to directly or indirectly cause Damage to the Environment and that are within the subject matter of required or potentially required state permits or agency actions” (“Expanded Environmental Notification Form”). His exact legal power is quite limited, however, as he notes, “MEPA is not a permitting process, and does not allow me to approve or deny a project. Rather, it is a process designed to ensure public participation in the state environmental permitting process, to ensure that state permitting agencies have adequate information on which to base their permit decisions…and to ensure that potential environmental impacts are fully described and avoided, minimized and mitigated to the maximum extent feasible” (“Expanded Environmental Notification Form”). The opponents to the project utilized his limited power to its full effect.

The goal of the letters was to both express opposition to the injustices of the problem and address areas of the filing that were problematic, in hope that Bowles would be thorough in critiquing the proponent. In total, Bowles received 761 comment letters critiquing EMI’s Expanded Environmental Notification Form and the Draft Environmental Impact Report (Estrella-Luna). The contents of the letters varied. The majority expressed concerns with health, the environment, and the proximity to the elementary school complex (Estrella-Luna). Other common themes were the “existing disproportionate environmental burden and existing high levels of poor health” and that “the power plant would be a setback to efforts to revitalize the city of Chelsea” (Estrella-Luna). Citizens as young as 15 wrote letters. Some comments merely read “No power plant in Chelsea.” One person wrote, “Personally, I think it’s bullshit” (Estrella-Luna). Some letters included detailed analyses of the documents themselves, noting issues in the filing process. The aiding environmental organizations helped these people sift through the documents, making the community members themselves the experts.

On May 18, 2007, Ian Bowles wrote that “at its proposed location, the project appears unlikely to be able to be permitted. If the proponent chooses to continue through the MEPA process, it does so at its own risk” (“Draft Environmental Impact Report”). He added that “many commenters have written with thoughtful and detailed recommendations regarding additional information and analysis needed, and I appreciate all the comments received” (“Draft Environmental Impact Report”) Merely six months later, EMI pulled out from the project. Perhaps they had not anticipated such intense resistance (Conti).

But this was not the first time Chelsea defeated the big corporation. In 1997, “residents denounced plans by a company to convert waterfront oil tanks into asphalt batching centers…later signed into law by then-acting governor Paul Cellucci, banning asphalt batching and storage plants from being placed near residential neighborhoods in three communities, including Chelsea” (Conti). The people of Chelsea have a fire within them, understandably from the years of environmental abuse they have received. Their persistence and strength in numbers shows that sometimes a judge is not required to save the community. As T.J Hellman, coordinator of Chelsea Collaborative’s Chelsea Green Space and Recreation Committee, put it, “it was beautiful to see so many in the community so united around this issue. You had people from second-graders at the complex writing letters to the governor, to people in their walkers protesting outside City Hall, and jam-packed meetings going to 11 o’clock. It was nice to see so many people mobilized around protecting Chelsea and Chelsea’s environment” (Conti). It was not lawyers protecting Chelsea– it was the people.

Works Cited

Bowles, Ian. “Certificate of the Secretary of Environmental Affairs on the Draft Environmental Impact Report.” Env.state.ma.us. May 18, 2007. Accessed April 16, 2016.http://web1.env.state.ma.us/EEA/emepa/pdffiles/certificates/051807/13927deir.pdf.

Bowles, Ian. “Certificate of the Secretary of Environmental Affairs on the Expanded Environmental Notification Form.” Env.state.ma.us. January 29, 2007. Accessed April 16, 2016. http://web1.env.state.ma.us/EEA/emepa/pdffiles/certificates/012907/13927eenf.pdf.

Casino, Paul G. “Meeting Notes.” Chelsea City Council, January 22, 2007, 0-30.

Conti, Katheleen. “No Power Plant, and Chelsea Cheers.” The Boston Globe, November 18, 2007. Accessed May 3, 2016. http://archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2007/11/18/no_power_plant_and_chelsea_cheers/.

Estrella-Luna, Neenah. Environmental Review in Massachusetts the Relationships, the Decisions, the Law: A Dissertation. PhD diss., Reproduction De: Dissertation (Ph. D.): Law, Policy and Society: Northeastern University, 2011.

Kelley, Scott. “Boston Area Residents Rally Against Proposal to Build Diesel Power Plant in Chelsea.” Boston Indymedia. January 9, 2007. Accessed May 3, 2016. http://boston.indymedia.org/feature/display/196128.

“STOP Energy Management Inc. From Building a Diesel Power Plant in Chelsea, MA.” Blogspot (blog), January 4, 2007. Accessed May 3, 2016. http://www.savechelsea.blogspot.com/.