Chloe Henderson

May 16, 2017

Engl 117 Cultural Theory Prof. Thorne

White Walls

He’s mostly known for “poppin’ tags” and going “downtown,” but there are other ways to read Macklemore’s music video “White Walls” than as mere signs of Cadillac admiration – it’s about race. No, not a race between two Cadillacs, I’m talking about the Black, White, Hispanic race that permeates American pop culture. It’s not unusual for Macklemore to talk about more than “the guns and the drugs / The bitches and the hoes and the gangs and the thugs” in his songs, but if the song title of this one wasn’t enough for you, then here it goes.

T he music video starts off in the countryside with Macklemore dressed up as a cross between a cowboy and a Mariachi band musician prancing around. As the Hispanic-country music blend finishes and an eagle squawks in the distance (reminiscing the end of traditional Western movies), the words “Starring Mackle Jackson” appear on the screen in cowboy font. Besides being an obvious pun, this name has other connotations.

he music video starts off in the countryside with Macklemore dressed up as a cross between a cowboy and a Mariachi band musician prancing around. As the Hispanic-country music blend finishes and an eagle squawks in the distance (reminiscing the end of traditional Western movies), the words “Starring Mackle Jackson” appear on the screen in cowboy font. Besides being an obvious pun, this name has other connotations.

First, Jackson is of Scottish origin and is a typically white name. It’s also a typical name of many cowboys, especially as “Jack,” such as the infamous cowboys like Jack Helm, Jack Dunlop, and Texas Jack, which could be reasoning as to why Macklemore chose to use this pun during his Western cowboy imitation. The use of cowboys in the beginning and end of “White Walls” could also be a reference to the song by Chris LeDoux, “Cadillac Cowboy,” which is about exactly what it sounds like y’all. But what’s more interesting is the pun’s most prominent association: Michael Jackson. There’s no way to mention Michael Jackson without talking about race – the man bleached his skin and had plastic surgery on every facial feature to completely change his own race while singing “it don’t matter if you’re black or white.” So what’s Macklemore got to do with calling himself “Mackle Jackson?”

The Washington-state grown liberal Macklemore is has been a champion of racial equality and an adamant supporter of Black Lives Matter for years. Just last January Macklemore released a song, “White Privilege II,” to raise awareness of racial injustice to get more white people to talk about race despite its growing sensitivity and discomfort as a topic of conversation. But Macklemore isn’t the first to talk about race in his songs. In fact, Michael Jackson’s Black or White was an open plea for racial harmony in 1991. So when Macklemore openly equates himself to Michael Jackson, he too is pleading for racial harmony, intermingling, and equality while offering himself as a racial justice advocate like Michael Jackson also did in his songs. Ok, so now back to “White Walls.”

Once the Hispanic-cowboy music fades out and the “White Walls” anthem begins, Macklemore is pictured singing with two identical Black women dressed in 70’s outfits clenching either of his arms. Macklemore is literally surrounded by Blackness belting “I wanna be free / I wanna just live” as if Blackness were a freedom to live away from the constraints of whiteness. This isn’t the only point in the video in which Black culture is offered as a freedom from (or alternative to) whiteness. As the video progresses into  the chorus, there is a party going on, but not the usual party you would imagine in a young rapper’s music video. It was a pool party with old women in swimsuits dancing, smoking, drinking, swimming, and even making out with young black men! This is Macklemore screaming for cultural intermingling between even the stereotypically most conservative people (old people) and Blackness. Not only should White people adopt Black culture though, but Black people should also adopt White culture. The video displays a young black man wearing a purple polo and white flat cap playing golf and croquet, typically White sports, as well as young Black men participating in a backyard picnic, a pillar of American White culture. By placing old women and young Black men unexpectedly in cross-racial stereotypical scenes, Macklemore is encouraging the blend of cultures and deletion of racial cultural boundaries while also claiming that participation in other cultures can be an escape for White people from the constraints of their Whiteness.

the chorus, there is a party going on, but not the usual party you would imagine in a young rapper’s music video. It was a pool party with old women in swimsuits dancing, smoking, drinking, swimming, and even making out with young black men! This is Macklemore screaming for cultural intermingling between even the stereotypically most conservative people (old people) and Blackness. Not only should White people adopt Black culture though, but Black people should also adopt White culture. The video displays a young black man wearing a purple polo and white flat cap playing golf and croquet, typically White sports, as well as young Black men participating in a backyard picnic, a pillar of American White culture. By placing old women and young Black men unexpectedly in cross-racial stereotypical scenes, Macklemore is encouraging the blend of cultures and deletion of racial cultural boundaries while also claiming that participation in other cultures can be an escape for White people from the constraints of their Whiteness.

Other cultures have often been seen as an escape for White people from the expected etiquette and civility that White culture carries. In his book Playing Indian, Philip Deloria  argues that throughout history White people have briefly adopted Indian culture to free

argues that throughout history White people have briefly adopted Indian culture to free

themselves from expected White civility, such as when the White colonists dressed as Indians to throw tea in the Atlantic during the Boston Tea Party or when “modern children of angst-ridden upper- and middle-class parents wore feathers and slept in tipis and wigwams at camps with multisyllabic Indian names” or when “World War II descendants made Indian dress and powwow-going into a hobby” (Deloria, 7). In each of these cases, the “uncivilized savagery” and “irrational violence” associated with Native Americans was  used as a disguise for White people to dress up and “play Indian” in order to express and free themselves from the constraints of Whiteness. This is analogous to White people today dressing up as Native Americans at music festivals and listening to rock and roll or rap (which both originated from Black culture) that talks about the drugs, sex, and rule breaking that most White conservatives are brought up to keep quiet. In the “White Walls” music video, one older White woman literally deserts her White trash life, White husband, and white trailer park home to go to the pool party to flirt, drink, and deep-throatedly make out with a young tattooed black man. Macklemore capitalizes on the freedom that “playing Indian” or “playing Black” or “playing Hispanic” provides by integrating various races around a common commodity: Cadillacs.

used as a disguise for White people to dress up and “play Indian” in order to express and free themselves from the constraints of Whiteness. This is analogous to White people today dressing up as Native Americans at music festivals and listening to rock and roll or rap (which both originated from Black culture) that talks about the drugs, sex, and rule breaking that most White conservatives are brought up to keep quiet. In the “White Walls” music video, one older White woman literally deserts her White trash life, White husband, and white trailer park home to go to the pool party to flirt, drink, and deep-throatedly make out with a young tattooed black man. Macklemore capitalizes on the freedom that “playing Indian” or “playing Black” or “playing Hispanic” provides by integrating various races around a common commodity: Cadillacs.

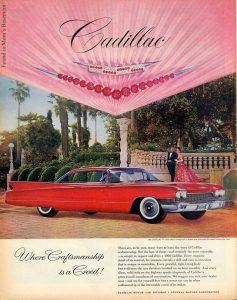

Cadillacs are unique in that they transcend racial boundaries. One historical stereotype

behind Cadillacs were that Cadillac Sedans were driven by old, rich conservative “Amuricans.” This was often seen in the company’s advertisements directed towards  wealthy White people who were pictured in extravagant dresses enjoying a better, quieter, more luxurious life with a new Cadillac. The company even used Christianity references to appeal to Whites claiming that Cadillacs are “Where Craftsmanship is aCreed!” (Advertisement, 1960). The rich White community Cadillacs appealed to also included many presidents and elites, such as President Hoover up through President Trump whose security posses solely drive black Cadillac SUV’s. In fact, the Cadillac One has been named the official Presidential State Car of the United States reflecting the car’s popularity among even the most elite and (besides the Obama administration) whitest of the country.

wealthy White people who were pictured in extravagant dresses enjoying a better, quieter, more luxurious life with a new Cadillac. The company even used Christianity references to appeal to Whites claiming that Cadillacs are “Where Craftsmanship is aCreed!” (Advertisement, 1960). The rich White community Cadillacs appealed to also included many presidents and elites, such as President Hoover up through President Trump whose security posses solely drive black Cadillac SUV’s. In fact, the Cadillac One has been named the official Presidential State Car of the United States reflecting the car’s popularity among even the most elite and (besides the Obama administration) whitest of the country.

The other historical stereotype behind the “most celebrated and sophisticated cars on the streets of the world” (Advertisement, 1929) was that Cadillac SUV’s were typically driven by Black rappers or gangsters. Interestingly enough, Black people actually saved Cadillac from bankruptcy when sales had plummeted during the Great Depression. Nicholas Dreystadt, the Cadillac manager, had “discovered that the car was very popular with the small black bourgeoisie of successful entertainers, doctors, and ghetto businessmen” (Cray, 279) and that Black men were actually paying White people to buy Cadillacs for them. According to American Professor, David Bell, “a Cadillac was a tool to further Blacks (at least in terms of image) along the road to equality…a solid and substantial symbol for many a Negro that he is as good as any White man…a demonstration that equality can be found” (Bell, 65). When this was discovered in 1932, a new series of advertising directed towards the Black community was initiated, causing Cadillac to be the first motor vehicle to have “diversity marketing” not necessarily by picturing Blacks in advertisements, but by openly selling to Blacks. This continued to spread the Cadillac’s popularity throughout the Black community, eventually leading to the creation of the Pimpmobile in the 1970s which originated in blaxploitation films. These films targeting Black viewers by featuring Black actors, playing funk and soul music soundtracks, and taking place in the ghetto with stereotypical depiction of Blacks dealing with pimps and drug dealers, adding to the rising popularity of Cadillacs in the Black community.

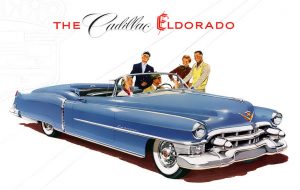

Not only were Cadillacs targeted towards both Blacks and Whites, but Cadillacs were also targeted towards the Hispanic community, especially once they were made into lowriders by Mexican-American Barrio youth in the 1950’s. In fact, in 1953 Cadillac released the Cadillac Eldorado which, as obvious as it sounds, used a name of Spanish origin to appeal to Hispanic buyers.

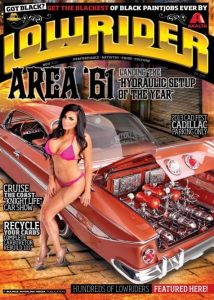

Not only were Cadillacs targeted towards both Blacks and Whites, but Cadillacs were also targeted towards the Hispanic community, especially once they were made into lowriders by Mexican-American Barrio youth in the 1950’s. In fact, in 1953 Cadillac released the Cadillac Eldorado which, as obvious as it sounds, used a name of Spanish origin to appeal to Hispanic buyers.  Cadillacs were also frequently featured in the LowRider Magazine as another means of appealing to Hispanics. Unlike many other car companies, Cadillacs both attracted and invited Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics, creating an aura of equality and connectedness among all races and cultures, much like Macklemore does in his songs.

Cadillacs were also frequently featured in the LowRider Magazine as another means of appealing to Hispanics. Unlike many other car companies, Cadillacs both attracted and invited Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics, creating an aura of equality and connectedness among all races and cultures, much like Macklemore does in his songs.

Macklemore surely incorporates each of these Cadillac stereotypes into his “White Walls” music video picturing a young Hispanic boy bouncing in his dad’s lowrider, an old White American man eating a burger in his Cadillac convertible, and a Black rapper “ridin’ real slow in [his] paint wet drippin’ shining like [his] 24’s.” Macklemore uses the different associations with Cadillacs to encourage the intermingling of cultures, races, and ages through this common commodity. But anyone who listens to Macklemore undoubtedly knows that he has a multicultural desire for sharing and equality. But what’s more is that in “White Walls” Macklemore sings, “I’m rollin’ in that same whip that my granddad had” claiming that the ability to share cultures and equally validate other races has been around for generations, just as Cadillacs have been. Yet on the contrary, so also has the ability to discriminate. We get many of our beliefs, values, and physical commodities from generations before us, yet we also get our prejudices from them. According to Professor David Bell, “The Cadillac has no prejudice” (Bell, 65). So by passing down Cadillacs through generations, we are also passing down “a weapon in the war for racial equality” (Bell, 65). However, in “White Walls” Macklemore sings about having “that off-black Cadillac” which makes it sound like although Cadillacs are popular among the Black community, they aren’t entirely Black, they’re “off-black.” So even though Cadillacs are a commonality throughout various cultures, they also have a different meaning in each culture that make them “off-Black,” “off-White,” or “off-hispanic.” The same four wheeled vehicle to a Black, White, or Hispanic person, has different associations for each culture (rich wealth for Whites, fame or status for Blacks, anti-Anglo cultural statements for Hispanics). So when Macklemore sings about Cadillacs, he isn’t just singing about a car. He’s singing about a commodity that has been consumed by Black people, White people, Hispanic people, old people, young people, men, women, and children to express themselves differently, but with a shared basic purpose of driving.

Macklemore recognizes that there’s a stigma against cultural appropriation, and as a White rapper in the hip-hop world, he is fully conscious of his own appropriation of Black culture. In his newest release, White Privilege, he admits his guilt for appropriating Black culture saying, “I give everything I have when I write a rhyme / But that doesn’t change the fact that this culture’s not mine.” Nonetheless, Macklemore’s entire career is attributed to Black culture. But what Macklemore suggests through his songs and particularly through “White Walls” is that cultural appropriation can be used to spread awareness and appreciation of other cultures and to become a more unified community of many races. Some, like James Young, author of Cultural Appropriation in the Arts argue that cultural appropriation “can harm insiders by misrepresenting them in certain ways…by employing bigoted stereotypes [so that] members of these cultures [are] subjected to terrible discrimination” (Young 107-108). And yes, it’s true that cultural appropriation can lead to discrimination, just like any image of another culture can lead to discrimination; but what Macklemore’s “White Walls” suggests is that instead of using cultural appropriation to build stereotypes, cultural appropriation can also be used to break stereotypes by sharing values and traditions of various races through cultural artifacts, like Cadillacs.

Cadillacs are a commodity that have been a “Favorite of All Nations” (Cadillac

Cadillacs are a commodity that have been a “Favorite of All Nations” (Cadillac

advertisement, 1955), and also a favorite of all races since 1955. And like their most recent commercial claims, Cadillacs have “carried a century of humanity – lovers, fighters, leaders” and have shared the message that “although we’re not the same, we can be one” (Carry Cadillac Commercial, 2017). This, too, is Macklemore’s message, and he uses Cadillacs as a vehicle to share this idea. Just as Cadillac has promoted and embraced shared commodities and culture across races, we too can try to tear down the white walls of white constraint, privilege, and “superiority” to create a more just, equitable society for everybody. A society where we can all “be free” and “just live inside [our] Cadillacs.”

References

Bell, D., & Hollows, J. (2006). Historicizing lifestyle: mediating taste, consumption and identity from the 1900s to 1970s. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Cadillac: Favorite of All Nations [Advertisement]. (1955).

Cadillac La Salle Wherever the Admired and Notable Congregate [Advertisement]. (1929, March).

Cadillac Where Craftsmanship is a Creed [Advertisement]. (1960).

Cray, E. (1980). Chrome Colossus: General Motors and Its Times. Mcgraw-Hill; First Edition edition .

Deloria, P. J. (2007). Playing Indian. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press.

James O. Young, Cultural Appropriation in the Arts (Blackwell Publishing, 2008).

LowRider Area 61 [Advertisement]. (2013). LowRider.

[Recorded by Macklemore, R. Lewis, & Hollis]. (n.d.). White Walls [CD]. Macklemore and Ryan Lewis.

This essay was read by Drew Cohen.

I have written this essay in the style of Greg Tate.

Prompt #6

of their culture – is simple and spent at home because of their limited income. Their culture is their money – or lack thereof. For

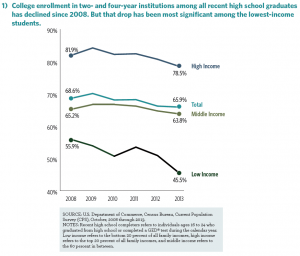

of their culture – is simple and spent at home because of their limited income. Their culture is their money – or lack thereof. For family because of their low economic status. This is equally true today. According to Census Bureau data from 2013, 78.5% of students from high income

family because of their low economic status. This is equally true today. According to Census Bureau data from 2013, 78.5% of students from high income professional writer. The professor claims that “only half a dozen [people] could support themselves as writers alone… so if you want to be an author and eat two or three times every day, there’s only one way to do it: marry money.” In this scene, the Walton’s economic status and their eldest son’s reality is exposed – his access to pursuing his dream career and culture is crippled by his poor background and lack of access to high culture. Because he doesn’t have the money to sustain himself as a writer alone (according to this professor) and since he hasn’t been exposed to high culture to have the connections to get published, the odds are stacked against JohnBoy to successfully become a writer, once again proving that culture, in the sense of career options, is not ordinary. Religion, on the other hand is a different story.

professional writer. The professor claims that “only half a dozen [people] could support themselves as writers alone… so if you want to be an author and eat two or three times every day, there’s only one way to do it: marry money.” In this scene, the Walton’s economic status and their eldest son’s reality is exposed – his access to pursuing his dream career and culture is crippled by his poor background and lack of access to high culture. Because he doesn’t have the money to sustain himself as a writer alone (according to this professor) and since he hasn’t been exposed to high culture to have the connections to get published, the odds are stacked against JohnBoy to successfully become a writer, once again proving that culture, in the sense of career options, is not ordinary. Religion, on the other hand is a different story.