As a feminist, I’m often totally disgusted by pop culture’s treatment of women in so many regards. I remember being a little girl, watching Disney princess movies and wondering—why do I need a prince to save me? Why couldn’t I just save myself, or perhaps, save the prince? But these were just little kid thoughts, I did not spend hours questioning the patriarchal framework of Disney movies. These issues became more apparent as I grew up. Not too long ago, I read about how, even at the editing level of movies, the male perspective is favored and women are there to, essentially, be looked at by men. This claim totally had me. I was ready to watch hours of film and shit on each and every one about how misogynistic and awful it was. But then I saw a horror film. I had never really seen one before, so it totally blew me away. Everything was so weird and atypical of what I’d anticipated in film. I was utterly confused. I thought I’d understood gender in pop culture, but this film made me question my beliefs. But of course, I didn’t want to change my beliefs. I love being right about things far too much. At the same time, I couldn’t just ignorantly hold views that could be totally inaccurate, so I watched another horror film—Sinister.

Now, I’m not sure how Sinister stands in comparison to horror film as a genre—it was honestly just the first horror movie I saw on Netflix. I know how fun digging around Netflix can be, but as busy college student, just watching a movie was already a stretch. Nevertheless, I was able to give up one pleasant evening in Williamstown to indulge in academic horror film consumption. I live my life with no regrets, this decision included. So the movie began and within the first few moments I could tell that a man was indeed the main character—there would be no final girl here. The final girl is a horror film motif describing the last girl alive who usually defeats the evil male killer by adopting typically male characteristics and, along the way, getting an audience of all genders to sympathize with her and see from her perspective. The first horror film I watched, Silence of the Lambs, had this feature, and in turn, casted uncertainty onto my view of movies as inherently favoring men. So picture me, all smiley in the middle of horror movie, mind you, because alas, I am not wrong about the sexist framework of movies after all! But this thought was oh so premature. It did not take long for the film to do some interesting things, making me question myself all over again.

Before discussing this male lead in g

Before discussing this male lead in g reater detail, you should know the basic story in Sinister: the male lead moves to a house to investigate and eventually write a book about a family who was mysteriously murdered there, but the incident is eventually interpreted as a pattern and his family is next. As you probably have guessed, they die. So then, who is this male main character? How is he portrayed in the story? We can begin with listing who he is not. He is not: epic badass fighter masculine guy. This, right away, sets him apart from the typical men that come to my mind in pop culture. In fact, he writes books for a living, one of the least macho professions. He is also fairly scrawny and weak looking, definitely not strong enough to take care of himself. He is, however, a smart and fairly brave man, which are qualities of a typical man’s portrayal. So the male lead is an interesting mix of masculinity and femininity and is seen, at least at the very end, as a weak victim. He is drugged and murdered by his own young daughter and an androgynous weird looking boogie man. I mean come on, any macho man could have defeated this iconic duo—but not Sir Writesalot here. Okay so we’ve established that he isn’t the toughest of men, but this really means nothing on its own. It is much more interesting to think about how this characterization affects an audience. First of all, viewers of all genders likely identify with him to some degree because he is the main character. I still think that male main characters are the most universally identified with, even when the agenda is not misogynistic. To some, the reasoning for this is that there are a disproportionate number of POV shots from the male perspective which, in turn, makes the male perspective the norm and forces it on everyone. I personally understand this phenomenon as a consequence of male leads dominating film, though I was, at one point, totally convinced by the former. Now, however, I see the claim as true in some situations, but inaccurate in that it cannot be understood as all encompassing. This idea is particularly lacking in the horror realm. In interpreting identification with the male lead while watching Sinister, it has little to do with forcing the male perspective upon the audience and more to do with the fact that he possesses qualities of both genders. This is quite strange if you think about it. Here is man that is manly and feminine and is identified with differently by men and women because of this. But all identification is with him as a person. This is not forcing us to believe that men are the best and that as women, I am here only to be looked at by a man—not even a little bit. This is telling us that, perhaps, gender should not be thought of as binary. Men can be masculine and also feminine to some degree.

reater detail, you should know the basic story in Sinister: the male lead moves to a house to investigate and eventually write a book about a family who was mysteriously murdered there, but the incident is eventually interpreted as a pattern and his family is next. As you probably have guessed, they die. So then, who is this male main character? How is he portrayed in the story? We can begin with listing who he is not. He is not: epic badass fighter masculine guy. This, right away, sets him apart from the typical men that come to my mind in pop culture. In fact, he writes books for a living, one of the least macho professions. He is also fairly scrawny and weak looking, definitely not strong enough to take care of himself. He is, however, a smart and fairly brave man, which are qualities of a typical man’s portrayal. So the male lead is an interesting mix of masculinity and femininity and is seen, at least at the very end, as a weak victim. He is drugged and murdered by his own young daughter and an androgynous weird looking boogie man. I mean come on, any macho man could have defeated this iconic duo—but not Sir Writesalot here. Okay so we’ve established that he isn’t the toughest of men, but this really means nothing on its own. It is much more interesting to think about how this characterization affects an audience. First of all, viewers of all genders likely identify with him to some degree because he is the main character. I still think that male main characters are the most universally identified with, even when the agenda is not misogynistic. To some, the reasoning for this is that there are a disproportionate number of POV shots from the male perspective which, in turn, makes the male perspective the norm and forces it on everyone. I personally understand this phenomenon as a consequence of male leads dominating film, though I was, at one point, totally convinced by the former. Now, however, I see the claim as true in some situations, but inaccurate in that it cannot be understood as all encompassing. This idea is particularly lacking in the horror realm. In interpreting identification with the male lead while watching Sinister, it has little to do with forcing the male perspective upon the audience and more to do with the fact that he possesses qualities of both genders. This is quite strange if you think about it. Here is man that is manly and feminine and is identified with differently by men and women because of this. But all identification is with him as a person. This is not forcing us to believe that men are the best and that as women, I am here only to be looked at by a man—not even a little bit. This is telling us that, perhaps, gender should not be thought of as binary. Men can be masculine and also feminine to some degree.

Now, you are probably curious about the male lead’s killers—the boogie man and the murderous child—too, as you should be, considering that they are both essential in explaining the film itself as well as its further implications. So let me start with the boogie man. I don’t know what preconceived ideas you have of what a boogie man looks like, but I’ll explained Sinister’s very own for you. The boogie man is lean and pale, with dark makeup and long black hair. I believe the common assumption is that the boogie man is, in fact, a man, but this is not so certain from looking at him. Makeup and long hair are typical features of women, while the long lean frame is more along the ones of a scrawny male. These characteristics, combined, make the boogie man appear to be quite androgynous. However, even with all of the uncertainty in the descriptors, for most of the movie, you never get a good glimpse of him anyways. He is always faded and appears briefly, at least until the end. As viewers, we spend a lot of time trying to figure out what this boogie man is. But even when we understand it as a man, it is difficult to see him as such. We have preconceived notions of “man,” so we are quite confused by this monster’s lack of clear gender. But the monster’s twisting of gender is even more complicated. The female horror film audience has been studied and understood to actually identify with this monster much more than men do. I can vouch for this to, as I found myself strangely drawn to the boogie man while watching Sinister. I was oddly satisfied whenever Mr. Boogie made a scare, particularly during a scene where his figure makes direct eye contact with the male lead from the bottom of a pool as a family is drowning. This may seem like something only a psychopath would feel, but trust me, I am not alone, though this may not at all rid you of judgement in my direction. But that’s what I’m getting at here—this, outwardly, makes no sense. Why the hell would weak and scared girls identify with this monster? This same study also showed that female audiences don’t look away much at all from the films, as many believe to be true. These two findings each help to explain the other. Let us first try to understand the identification bit. Monsters live in a world that is dominated by men who are trying to hunt and kill them. Now, at least in my life, I do not have men trying to murder me, but I do live in a society hounded by the male gender. On the grounds of this shared experience, does it not makes sense to relate? I think it does. And why would a girl want to look away when she sees a monster sharing her experience and coming out on top? The monster’s androgyny is interesting as it is, but adding female identification with this monster gives way to a whole new and perplexing idea. Women identifying as a monster may, at least for a brief moment, feel power to rise above the man, who is portrayed in this film as a weak victim. And male viewers, who rarely identify with the monster, are being defeated. This seems to me strategically feminist. Women are given power that is not a, so called, norm—all from identifying with a creepy, androgynous monster.

Now, you are probably curious about the male lead’s killers—the boogie man and the murderous child—too, as you should be, considering that they are both essential in explaining the film itself as well as its further implications. So let me start with the boogie man. I don’t know what preconceived ideas you have of what a boogie man looks like, but I’ll explained Sinister’s very own for you. The boogie man is lean and pale, with dark makeup and long black hair. I believe the common assumption is that the boogie man is, in fact, a man, but this is not so certain from looking at him. Makeup and long hair are typical features of women, while the long lean frame is more along the ones of a scrawny male. These characteristics, combined, make the boogie man appear to be quite androgynous. However, even with all of the uncertainty in the descriptors, for most of the movie, you never get a good glimpse of him anyways. He is always faded and appears briefly, at least until the end. As viewers, we spend a lot of time trying to figure out what this boogie man is. But even when we understand it as a man, it is difficult to see him as such. We have preconceived notions of “man,” so we are quite confused by this monster’s lack of clear gender. But the monster’s twisting of gender is even more complicated. The female horror film audience has been studied and understood to actually identify with this monster much more than men do. I can vouch for this to, as I found myself strangely drawn to the boogie man while watching Sinister. I was oddly satisfied whenever Mr. Boogie made a scare, particularly during a scene where his figure makes direct eye contact with the male lead from the bottom of a pool as a family is drowning. This may seem like something only a psychopath would feel, but trust me, I am not alone, though this may not at all rid you of judgement in my direction. But that’s what I’m getting at here—this, outwardly, makes no sense. Why the hell would weak and scared girls identify with this monster? This same study also showed that female audiences don’t look away much at all from the films, as many believe to be true. These two findings each help to explain the other. Let us first try to understand the identification bit. Monsters live in a world that is dominated by men who are trying to hunt and kill them. Now, at least in my life, I do not have men trying to murder me, but I do live in a society hounded by the male gender. On the grounds of this shared experience, does it not makes sense to relate? I think it does. And why would a girl want to look away when she sees a monster sharing her experience and coming out on top? The monster’s androgyny is interesting as it is, but adding female identification with this monster gives way to a whole new and perplexing idea. Women identifying as a monster may, at least for a brief moment, feel power to rise above the man, who is portrayed in this film as a weak victim. And male viewers, who rarely identify with the monster, are being defeated. This seems to me strategically feminist. Women are given power that is not a, so called, norm—all from identifying with a creepy, androgynous monster.

So far, we’ve got a feminine, yet manly male lead, and an androgynous monster, both very strange compared to gender as many understand it…so what’s with the child killer? The boogie man is followed around by an ever growing group of devil children, each of whom he’s made murder their family. This film, for reasons I will soon bring to light, chose to make this devil child a girl. So let us discuss this devil girl as a concept. Girls are young women and are, therefore, children of innocence, purity, and civility by association. This makes them most susceptible to corruption. But when these young girls are corrupted, they gain a lot of power—their weakness became their strength. This particular girl fits all of these ideas. She is a seemingly sweet and innocent as a talented little artist, but her innocent and sweet art becomes devilish when she begins to paint murderous children and the boogie man’s sign. Furthermore, she uses her family’s freshly murdered blood to paint innocent girly animals, one being unicorns, all over the walls. I’m picturing unicorns painted in blood right now actually, and let me tell you, it is quite unsettling, and rather disgusting. This child’s ultimate display of evil innocence, however, is when she leaves a note with her father’s drugged coffee reading—“Good Night Daddy”—meant to indicate that he is about to die by her hand. But in any other context, this is just a cute note any little girl who loves her father would write. This girl, as a young female, is given enough power to kill her father, the male lead, and the rest of her family, through evil innocence. This is weird when looking at the bigger gender picture. A little girl, seen as the weakest of all people, has an unfathomable amount power—enough to murder her entire family. Compared to her brother, who often gets night terrors because of the haunted nature of their home, she seems even more powerful, as she is feeding off of the murderous and evil energy. So even on the level of children, gender is super messy. This little girl should be the weakest character in the entire film if we don’t veer from what we think of as normal gender roles, but she is nearly the most powerful, second only to the rough and tough Mr. Boogie. I’m not sure how people identify with this child in general, but I, personally, found myself in awe of her. I mean, who doesn’t fantasize about a little girl working with a monster to rise above the man. What I’m saying is, this is the dynamic duo of my dreams. I identify with the male monster and feel a connection to the child at the same time.

At this point, I can clearly see a gender story. It seems to be feminist in nature, as there are no totally masculine characters at all. The male lead, who is the most masculine of all characters, is hardly manly. He is weak and pitted against the powerful evil beings—a monster whom women identify with, and a badass, devilish girl, whose innocence is her power. This story alone is pretty weird in terms of understanding gender. It has subverted everything I think of as typical gender roles, and everything I thought was typical about gender in film. It is not forcing the male perspective on viewers, but rather giving females more power in terms of the female character, and promoting female identification with the most powerful characters. So I should feel totally in support of the evil side, but there is still a part of me identifying with the feminine aspects of the male lead as well. On top of this, the idea of siding with evil seems morally unsettling to me. And what does it mean that even though the male lead is weak, he is still on the side of good in a good versus evil scenario? With all of this in mind, I am, honestly, still trying to piece together how I feel about each character. Regardless, my one definite take away is just how goddamned confusing gender is in this movie. Silence of the Lambs was not an anomaly, as Sinister threw some mystifying gender stuff my way just the same. I cannot mindlessly continue to think that all movies inherently favor the male when I’ve shown myself just how untrue this can be. In a way, the lack of clarity in Sinister’s gender bending emphasises this point even more—gender is just too confusing to make broad claims about. You can look for patterns and try to understand each film’s individual gender story, but there is not one all encompassing truth. But I’m fine with this—I can’t wait to spend hours of summer freetime analyzing various movies and finding out what each one has to say about gender. Will there be any correlation? Or will the crazy confusion prevail in its purest form? There’s only one way to find out, and I intend to do so.

This essay was written in the style of Chuck Klosterman

This essay was read by Chloe Henderson

Works Cited

Cherry, Brigid. “Refusing to Refuse to Look: Female Viewers of the Horror Film.” Identifying Hollywood’s Audiences. Ed. Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby. London: BFI Publishing, 1999.

Clover, Carol J. Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. S.l: British Film Institute, 1993.

Creed, Barbara. “Baby Bitches From Hell: Monstrous Little Women in Film.” Scary Women. N.p., Jan. 1994.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Media and Cultural Studies : Keyworks. Eds. Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

he music video starts off in the countryside with Macklemore dressed up as a cross between a cowboy and a Mariachi band musician prancing around. As the Hispanic-country music blend finishes and an eagle squawks in the distance (reminiscing the end of traditional Western movies), the words “Starring Mackle Jackson” appear on the screen in cowboy font. Besides being an obvious pun, this name has other connotations.

he music video starts off in the countryside with Macklemore dressed up as a cross between a cowboy and a Mariachi band musician prancing around. As the Hispanic-country music blend finishes and an eagle squawks in the distance (reminiscing the end of traditional Western movies), the words “Starring Mackle Jackson” appear on the screen in cowboy font. Besides being an obvious pun, this name has other connotations.  the chorus, there is a party going on, but not the usual party you would imagine in a young rapper’s music video. It was a pool party with old women in swimsuits dancing, smoking, drinking, swimming, and even making out with young black men! This is Macklemore screaming for cultural intermingling between even the stereotypically most conservative people (old people) and Blackness. Not only should White people adopt Black culture though, but Black people should also adopt White culture. The video displays a young black man wearing a purple polo and white flat cap playing golf and croquet, typically White sports, as well as young Black men participating in a backyard picnic, a pillar of American White culture. By placing old women and young Black men unexpectedly in cross-racial stereotypical scenes, Macklemore is encouraging the blend of cultures and deletion of racial cultural boundaries while also claiming that participation in other cultures can be an escape for White people from the constraints of their Whiteness.

the chorus, there is a party going on, but not the usual party you would imagine in a young rapper’s music video. It was a pool party with old women in swimsuits dancing, smoking, drinking, swimming, and even making out with young black men! This is Macklemore screaming for cultural intermingling between even the stereotypically most conservative people (old people) and Blackness. Not only should White people adopt Black culture though, but Black people should also adopt White culture. The video displays a young black man wearing a purple polo and white flat cap playing golf and croquet, typically White sports, as well as young Black men participating in a backyard picnic, a pillar of American White culture. By placing old women and young Black men unexpectedly in cross-racial stereotypical scenes, Macklemore is encouraging the blend of cultures and deletion of racial cultural boundaries while also claiming that participation in other cultures can be an escape for White people from the constraints of their Whiteness.  argues that throughout history White people have briefly adopted Indian culture to free

argues that throughout history White people have briefly adopted Indian culture to free used as a disguise for White people to dress up and “play Indian” in order to express and free themselves from the constraints of Whiteness. This is analogous to White people today dressing up as Native Americans at music festivals and listening to rock and roll or rap (which both originated from Black culture) that talks about the drugs, sex, and rule breaking that most White conservatives are brought up to keep quiet. In the “White Walls” music video, one older White woman literally deserts her White trash life, White husband, and white trailer park home to go to the pool party to flirt, drink, and deep-throatedly make out with a young tattooed black man. Macklemore capitalizes on the freedom that “playing Indian” or “playing Black” or “playing Hispanic” provides by integrating various races around a common commodity: Cadillacs.

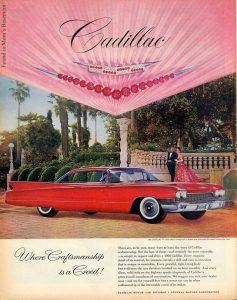

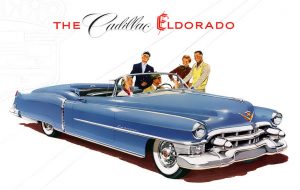

used as a disguise for White people to dress up and “play Indian” in order to express and free themselves from the constraints of Whiteness. This is analogous to White people today dressing up as Native Americans at music festivals and listening to rock and roll or rap (which both originated from Black culture) that talks about the drugs, sex, and rule breaking that most White conservatives are brought up to keep quiet. In the “White Walls” music video, one older White woman literally deserts her White trash life, White husband, and white trailer park home to go to the pool party to flirt, drink, and deep-throatedly make out with a young tattooed black man. Macklemore capitalizes on the freedom that “playing Indian” or “playing Black” or “playing Hispanic” provides by integrating various races around a common commodity: Cadillacs.  wealthy White people who were pictured in extravagant dresses enjoying a better, quieter, more luxurious life with a new Cadillac. The company even used Christianity references to appeal to Whites claiming that Cadillacs are “Where Craftsmanship is aCreed!” (Advertisement, 1960). The rich White community Cadillacs appealed to also included many presidents and elites, such as President Hoover up through President Trump whose security posses solely drive black Cadillac SUV’s. In fact, the Cadillac One has been named the official Presidential State Car of the United States reflecting the car’s popularity among even the most elite and (besides the Obama administration) whitest of the country.

wealthy White people who were pictured in extravagant dresses enjoying a better, quieter, more luxurious life with a new Cadillac. The company even used Christianity references to appeal to Whites claiming that Cadillacs are “Where Craftsmanship is aCreed!” (Advertisement, 1960). The rich White community Cadillacs appealed to also included many presidents and elites, such as President Hoover up through President Trump whose security posses solely drive black Cadillac SUV’s. In fact, the Cadillac One has been named the official Presidential State Car of the United States reflecting the car’s popularity among even the most elite and (besides the Obama administration) whitest of the country.  Not only were Cadillacs targeted towards both Blacks and Whites, but Cadillacs were also targeted towards the Hispanic community, especially once they were made into lowriders by Mexican-American Barrio youth in the 1950’s. In fact, in 1953 Cadillac released the Cadillac Eldorado which, as obvious as it sounds, used a name of Spanish origin to appeal to Hispanic buyers.

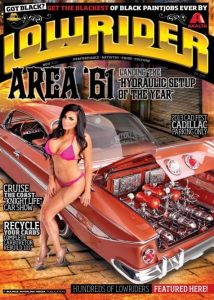

Not only were Cadillacs targeted towards both Blacks and Whites, but Cadillacs were also targeted towards the Hispanic community, especially once they were made into lowriders by Mexican-American Barrio youth in the 1950’s. In fact, in 1953 Cadillac released the Cadillac Eldorado which, as obvious as it sounds, used a name of Spanish origin to appeal to Hispanic buyers.  Cadillacs were also frequently featured in the LowRider Magazine as another means of appealing to Hispanics. Unlike many other car companies, Cadillacs both attracted and invited Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics, creating an aura of equality and connectedness among all races and cultures, much like Macklemore does in his songs.

Cadillacs were also frequently featured in the LowRider Magazine as another means of appealing to Hispanics. Unlike many other car companies, Cadillacs both attracted and invited Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics, creating an aura of equality and connectedness among all races and cultures, much like Macklemore does in his songs.  Cadillacs are a commodity that have been a “Favorite of All Nations” (Cadillac

Cadillacs are a commodity that have been a “Favorite of All Nations” (Cadillac