Why do we tell stories? To inform? To entertain? While there are many short, simple answers, most are too weak to fully explain the existence of such a longstanding and prominent cultural phenomenon. Looking for an answer to this question through a general analysis of stories misses the richness associated with any individual story. By analyzing an individual story, the features which distinguish stories as a component of our culture become apparent. American History X is an excellent example of such a story. In evaluating this movie, one can lose oneself in its emotional undulations and become immersed in the movie’s variations on the defining elements of a story. These elements arise at a deep level of the story, a level of political content. It is here that we find one answer to the question of why we tell stories. This answer is in the form of a pair of components that are universal among all stories. That is, all stories illustrate some conflict, and then provide solutions for that conflict. The effectiveness of this process is, in large part, why stories are so valuable to us as a method of communication.

As we established above, engaging in any generic analysis of stories is challenging. As a consequence, it’s difficult to determine what to begin looking for in American History X. Seeing as no clear strategy presents itself, a chronological approach is a natural method to default to. The movie begins with one of the two main characters, Danny Vineyard, taking a special, individualized course from his high school principle in an effort to both educate and discipline him. The course is called “American History X”, and Danny is assigned to write a paper about his brother Derek, a former Neo-Nazi. The story proceeds to follow Danny’s development through his youth and Derek’s development into a Neo-Nazi, as well as Derek’s prison time for manslaughter of two burglars, and the brothers’ eventual rejection of Neo-Nazi values and organizations. With this brief summary for the sake of continued reference, we can turn to analyzing the story’s opening.

The story wastes no time in establishing a problem. It doesn’t lull the reader into a long tale absent of adversity, confusion, and surprise. Immediately, it presents Danny’s ultraconservative and discriminatory views as challenges for him to live with. His negative attitude toward a wide swath of society, minority groups in particular, predisposes his peers to disdain him. And his actions do no service in endearing him to them either. The reason Danny is initially made to take “American History X” is his submission of an essay on Mein Kampf to his Jewish English teacher. For Derek, the trouble his views lead him to is even greater. His radical attitude causes him be scorned by his mother and sister. Additionally, his aggressive suppression of minorities in his community leads him to prison time.

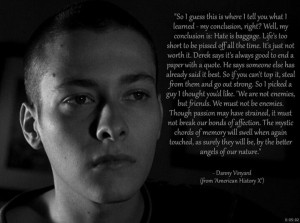

Beyond vividly establishing this problem, the story provides a clear solution. In Danny’s voiceover, following his murder by a fellow student, he denounces hate. This can easily be seen, in the context of Neo-Nazi elements of the story, as a rejection of ultraconservative views which center around antagonism toward minority groups. Hence, a solution is found in this final realization that people must not adopt such hateful viewpoints.

Thus, American History X makes a couple components of its storyline very clear. It presents a conflict. And it shows the audience a solution to that conflict. These literary features that American History X highlights point to a couple of candidates for key features of stories more broadly: the presentation of a conflict, and the illustration of corresponding solutions. But we need something more compelling than these overtly made points to suggest that this structure for stories is universal.

The question then is, what is present at a deeper level in all stories? Is there an underlying element of stories that binds them to some general structure? For an answer to this question we can turn to the theories of Louis Althusser. Althusser argued that ideology is present in all literary content. By Althusser’s definition, ideologies are the secret political contents that underlie literature, films, and other forms of communication. Almost no content can escape the presentation of some sort of ideology. Even the simplest articles, essays, or films have some underlying assumptions. The collection of these assumptions and more complex, hidden messages makes up the secret content, or ideology, of a work.

Ideologies in stories manifest themselves no differently. We can observe this through the lens of American History X. While the movie explicitly presents the conflicts and solutions illustrated in the paragraphs above, it conveys far more than that. Like other stories, American History X presents political ideas that are, at least partially, buried.

The best point at which to begin searching for the hidden political statement of the movie is Danny’s final voiceover. In the event that the audience has failed to that point at identifying the solutions to the problems with an ultraconservative political movement, Danny’s final words package up this message. However, what Danny specifically says is “Hate is baggage” and “Life’s too short to be pissed off all the time.” This quote occurs for a matter of seconds at the end of a multiple hour film which gave a disturbing portrayal of the Neo-Nazi movement. As a result, the natural effect of this statement is to reinforce the problems with this hateful movement to the audience. But, in actuality, the statement goes beyond this in scope. Danny’s rejection of hate extends beyond the Neo-Nazi movement to far less radical and more trivial forms of hate.

This is the secret political content of the film. When examining Danny’s remark in a vacuum, the content may not seem secret. But in the context of the entire film, the immediate impact of this quote on the audience is far more narrow than the explicit content of the statement itself. The hidden statement, that hate is baggage, is evidenced throughout the film. Derek’s father, shown during Derek’s youth in the movie, is portrayed as aggressively condemning affirmative black action in front of Derek. He argues against the increase of black literature in English classes and questions the appropriateness of hiring black individuals who scored relatively low on the fire-fighting test to serve alongside him at the department. Such vehement opposition to full, equal opportunity, and the employment of hate speech, which he uses to make the argument, is classifiably hateful. Although less severe and extreme than Neo-Nazism, the story sends a signal that hateful behavior is not rewarding, as the father is murdered by a drug dealer at the scene of a fire. Another example of this is apparent in Danny’s behavior and fate. While Danny holds ultraconservative views throughout most of the movie, he never wears his politics on his sleeve to nearly the extent that Derek does at the zenith of his Neo-Nazi career. In spite of this, Danny is still murdered at the end of the film. This evidence leads us toward a conclusion. Hate, however trivial, has a negative impact on our lives. Be it extreme, hateful political action, or guarded personal beliefs, when we harbor hate, we carry it with us everywhere and it harms our lives and those of others.

From this, it’s clear that American History X lends support to Althusser’s argument. The secret content to the story is that, in a political context or elsewhere, when people carry hate with them, it is to the detriment of them and those around them. In addition to supporting and exemplifying Althusser’s argument, American History X extends his claim. Not only does it present its claim about hate as a hidden ideology, but it does so in a very specific manner. The film shows hateful attitudes and behavior as a collective problem, and identifies living with openness and joy, free of hate, as a solution. In this way, the story of American History X presents hidden political content by showing a point of conflict and suggesting solutions.

We began by asking, why do we tell stories? Now, we have one of several important answers to this question. Stories allow us to disperse political content surreptitiously by weaving a message into a story, drawing the reader into it, and causing them to subconsciously absorb it. As American History X has highlighted, the hidden content of stories is not conveyed in any arbitrary fashion, but rather, occurs specifically through the identification of a problem and corresponding solutions. This style of presentation gives stories persuasive power that logical arguments for a claim often lack in spite of their superior clarity. In the case of American History X, the conflict facing the main characters was their hateful nature, and their solution was, quite simply, to be less hateful and more kind and open toward others. When searching for commonalities among stories, it is useful to look at a story through the lens of Althusser, who views the forwarding of ideology as a universal constant among stories. In doing so, we were able to observe the establishment, below the surface of the plotline, of a conflict and solution which allowed us to extend Althusser’s claim.

References:

[1] Althusser, Louis. “Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays.” La Pensée (1970): 52-116. Web. 18 Mar. 2016.

Image Sources:

[1] https://www.pinterest.com/explore/american-history-x/

[2] https://play.google.com/store/movies/details/American_History_X?id=Q6jCuiRjg4Q