2013 was a rough year for Washington D.C. Two movies, Olympus Has Fallen and White House Down, hit the screens within four months of each other. Both featured hostile takeovers of the White House. Olympus Has Fallen had a budget of $70 million, and White House Down $150 million. Today, movies’ production costs are barriers to entry for the film industry. Even independent films like It Follows, Juno, and Donnie Darko have budgets in the millions. What are the consequences when the cost of producing the art medium restricts access to all but an elite group? If elites control cinema, the art produced can manipulate viewers to sustain the status quo, and the associated distribution of power and wealth. In this analysis of the film industry, and Olympus Has Fallen in particular, I examine whether common culture or the culture industry more accurately explains film.

Cultural theorist Raymond Williams believed that common people, not the bourgeoisie, produce common culture (Williams 8). Williams’ beliefs stem from his rural upbringing and his observations of culture in 20th century Britain. He was born in Wales in 1921. His father was an uneducated railway signalman. He attended Cambridge University on scholarship where he studied under fellow cultural theorist Matthew Arnold (Brochu 1). Arnold thought that society could free itself from the oppressive elite if the majority of society read literary criticism; a solution to his perception of cultural woes. Williams disagreed with Arnold’s theory. In his childhood, he experienced rural folk culture where community members told each other stories and fables, played folk music, organized community events, and helped each other in times of need. These experiences lead Williams to the conclusion that culture means two things: a whole way of life and “the arts and learning ‒ the special processes of discovery and creative work” (Williams 4). Culture is both the art that is produced and the way that society carries on in day-to-day life. All together, Williams rejected the notion that a special class holds a monopoly over the creations of “common meanings” and art. For Williams, culture is common and classless in the creation of meanings, values, arts, and learning. Common culture is art that is produced by average people, it is not oppressing society. Common culture is the music you hear at open mic night. It is the graffiti you see on walls and trains.

Today six corporations produce 90% of all of that we read, watch, and hear (Lutz 1); to say that all art is common culture is naive. We live in an era that reflects cultural Marxism. Williams drew his ideas regarding ideal cultural equality from Marxists but disagreed with the central existence of an elite, oppressing class that controls culture. He shouldn’t have, at least with regards to film. According to Marx, “ideology” describes how “dominant ideas of a given class promote the interests of that class and help cover over oppression, injustices, and negative aspects of a given society” (Kellner 1). During the capitalist era (present day America), these values are competition and dominant markets. Both are expressed throughout this movie.

Olympus Has Fallen takes place in a modern but fictional Washington D.C. The story begins with a meeting between the President and the South Korean Prime Minister. During the meeting, North Korean terrorists capture the White House and hold everyone hostage. Their goals are to kill the Prime Minister, force the US to remove troops from the Korean region, and destroy America’s nuclear stockpile in their silos. In the midst of this assault, a Secret Service agent, Banning, joins the fight against the North Koreans. He begins a campaign to rescue the President and save the world with brutal, ruthless efficiency. He appears to take pleasure in breaking necks and torturing people. After Banning takes out most of the terrorists, he fights their leader and violently stabs him in the head. With seconds to spare, he stops the entire American nuclear stockpile from detonating and turning the country into a dystopian wasteland.

This movie typifies the mainstream film industry as a whole. It negates the common culture belief Williams proposed. With a budget of $70 million, only Hollywood studios are able to create this type of movie. A common artist, disconnected from the industry’s elite, is unable to produce a film projected on 3,000 screens in the opening weekend. Movies require thousands of man hours to create, expensive equipment, connections, and professional skills that often require higher education. The director of Olympus Has Fallen, Antoine Fuqua, has a net worth of $18 million and is one of the 54 richest black male celebrities (Riley 1). This work of culture is not classless. Millennium Films, the company that produced it, releases 5-8 movies a year with budgets between $20-80 million. It employs some of the richest artists in the world. When more than 90% of the culture we consume is controlled by an elite class, the commoner’s best interest will typically be overlooked. This monopoly lets the elite become richer and advances their political interests through the control of media images, stories, symbols and morals.

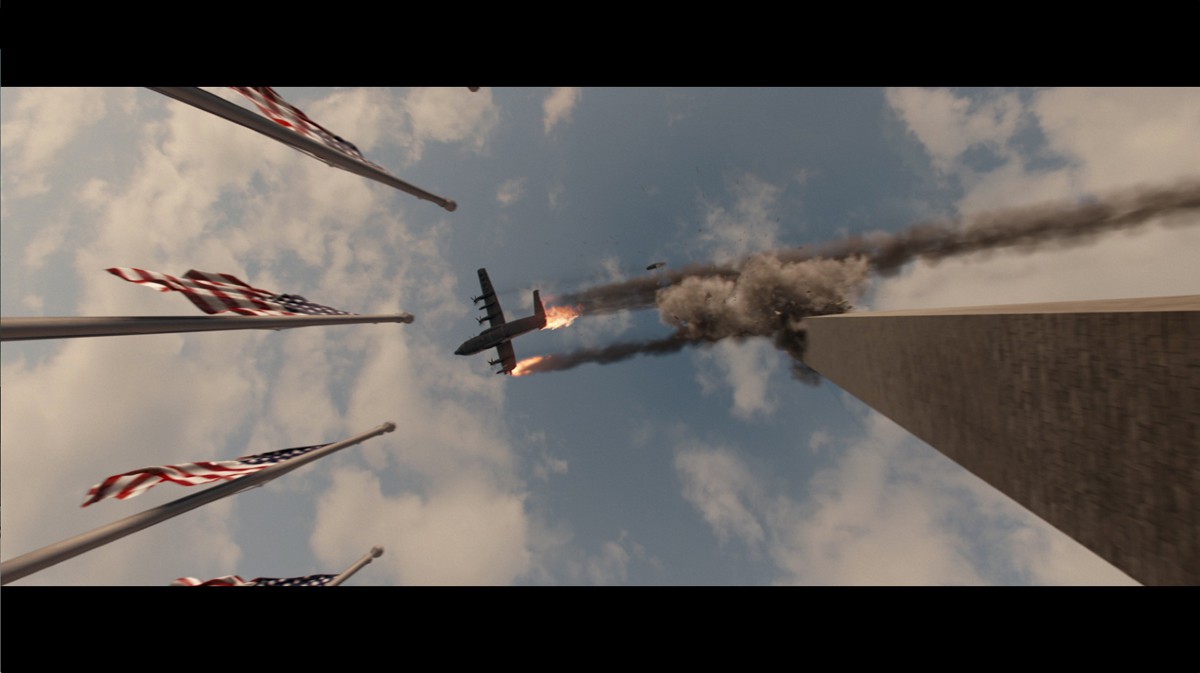

A closer look into the film’s storyline and values reveals its elitist values. Noah Berlatsky argues that the film does not reflect American principles in his article “The Vile, False Patriotism of ‘Olympus Has Fallen’” published in The Atlantic. He states the film is “a shameless exploration of the worst aspects of the American psyche” (1). When the North Koreans attack D.C., the film shows a plane crash into the Washington Monument for no reason other than to evoke images of 9/11 (2).

The movie attempts to normalize ‒ even glorify ‒ violence. It depicts 130 violent deaths in all fashions: knives, guns, explosions, dog attacks, and hand-to-hand combat. We are entertained by the violence in action movies. In fact, some people even clap for it. It’s plausible that the culture industry has supersaturated movies with violence to numb audiences to the atrocities of war. We distance ourselves from the bloodshed, and, in doing so, allow for its repetition throughout society.

These mores, do not reflect the common values of American society: they manipulate them. The movie strokes backward-thinking nationalism imposed on society by the elite for millennia. Culture suggests that in order to be a global power, we have to fear foreigners. The writers hilariously overstate North Korea’s military power. The country where 84% of the population has “borderline” to “poor” levels of food consumption (Stanton, Lee 1) and a history of military failures. The United States spends more on its military than the next seven countries combined; North Korea isn’t in the top 20 (PGFP 1). North Korea could never conduct a coordinated operation like the one depicted in Olympus Has Fallen. The writers appear to make North Korea the villain because the country has an unstable government, potential for nuclear weapon production, and borders an ally in the region. The movie stokes the fires of nationalism and insecurity at all costs. It encourages the audience to support military spending to prevent our homeland from an imaginary enemy. The values this film advances are created by conservative cultural elements in certain sectors of the film industry.

The culture industry is not unified in its messages, values, and ideologies. While Hollywood is largely liberal, Millennium Films almost exclusively makes patriarchal shoot-em-up movies reflecting more conservative values. Millennium films was co-founded by Avi Lerner: an Israeli-American who fought in the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War and is worth $150 million. He made his money producing movies such as The Expendables franchise and Homefront. With a military background and roots in Israel, Avi has reasons to support military spending and nationalism in his movies.

I will not, however, mislead my reader into believing action movies exclusively have political motives. Action movies are supplied because they are demanded by society and profits are a powerful motivator. Maybe there is an element of common culture that begs for brutal entertainment. This sentiment is reflected throughout history: gladiators, wrestling, boxing, etc. The power of “bread and circuses” was understood as far back as Emperor Augustus as a means to satiate the masses.

The state of the economy in 2013 could explain the production of two action movies about an assault of the White House. Matt McCaffery writes that “popular art often mirrors common ideas about current economic affairs and reflects the conventional wisdom guiding public opinion” (1). It appears that Olympus Has Fallen uses the Great Recession and North Korean instability to appeal to the fears of the masses. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, published an article in 2013 stating that US military preparedness has been undermined by the Budget Control Act (2011). The article states, “Regrettably, world events and potential threats to U.S. strategic national interests are not driven by the same forces that drive the political and budgetary gridlock in Washington. North Korea’s increasingly bellicose rhetoric and actions endanger regional stability in the economically vital Western Pacific” (Dunn 12). Conservatives see recessionary budget cuts as threats to our national security. What better method is there to nurture and ignite support for the military then to exaggerate a Korean threat in a major motion picture?

Maybe common culture is not expressed in film and television because individuals can change as they gain access to power and wealth and lose touch with common values. Williams himself started off as a commoner but once he received a scholarship to study at one of the most prestigious universities in the world he became elite. He can reflect on his common experiences from his childhood, but can he really make a “common” claim now that he is educated? This area of ambiguity presents problems for the proponents of common culture. Antoine Fuqua appears to follow a similar change from common culture to elite culture. He grew up a black man in Philadelphia, a minority in the city. He lost his common identity once he created music videos for big artists and action movies for Hollywood. With a networth of $18 million and a degree in electrical engineering, does he really think about the common culture of his youth, or is he largely influenced by his new community of high-net worth producers, directors and megastars? I believe that money and elite education generally distance individuals from common culture.

Pierre Bourdieu states that to be able to analyze culture, culture has to be restricted to its normative, anthropological sense. The elaborate taste for the most refined objects is as natural as tasting food (1). When an audience looks at Olympus Has Fallen in this light, the film’s elements suggest that the elites behind the film capitalized on the financial and psychological insecurity of its audience during 2013, and promoted their values of military strength and economic dominance to keep conservatives in power.