Game of Thrones Fans: Pawns On The Chessboard?

What role do fans play in the culture they consume? This is the question I’ve been battling while exploring the relationship between the hit series Game of Thrones and its consumers. Do fans actively adopt the series and have a role as creators? Or are they simply part of the culture industry machine, one that churns out content and systematically commercializes certain parts of fan culture? Today more than ever, the convergence of culture into every corner of our lives has made the divisions between producers, content, and consumers more fluid than ever. Whether this gives fans new power or simply signals a re-ordering of the culture industry is a significant question; it implicates if fans are finding new ways to subvert the culture industry – or whether they are becoming more entangled in the web of powerless consumerism. By examining the relationship of Game of Thrones fans – and in particular a pair who have become important collaborators to the author George RR Martin’s writing – I hope to uncover what exactly the state of fans in our society is today.

Game of Thrones is the source of one of the largest and most active fan cultures today. The series, which is simultaneously a book series by George RR Martin (yet to be finished) and a television show, has a rabid fan-base that first grew mostly online when the first books were published and has recently exploded with the introduction of the show. Like other popular series the fan culture involves online forums, conventions, cosplay, fan fiction, and lots of active communication towards both the author and the show’s producers. The show, based on a fictional world known as Westeros that resembles a medieval time imbued with magic, is famous for its complex storytelling and repeated killing of popular characters. The many facets and plotlines, along with the extreme popularity of the show have given birth to thousands of consumer creations, from fiction to digital recreations of the fantasy world. The important question, however, is if these fans are simply consumers with little true agency or do they represent a wave of creativity that allows them to influence the show and simultaneously side-step the grip of the culture industry?

First I think it’s prudent to layout what some fans of the series are doing. When the series was just books, there was a large community of online forums discussing the show at great length. As the show has come into popularity this discourse has spilled over almost everywhere, blurring the line between casual fans and those engaging in true fan cultures. When I use the term fans I mean those that try to take some part of the chronicle and either re-interpret it or re-imagine it. This includes the plenty of online fan fiction pieces as well as alternative storylines that have been disseminated around the Internet. There are also thousands who create costumes, engage in role-playing, and meet other fans at both physical and electronic gatherings. Furthermore there are fascinating pieces of art dedicated to the series; everything from paintings to iron throne toilets now adorn various parts of the world. In one sense, this allows fans to interpret Game of Thrones anyway they want, and take it in new directions if they choose. Henry Jenkins describes fan creations by saying “Their works appropriate raw materials from the commercial culture but use them as the basis for the creation of a contemporary folk culture.” Unlike content created by the series itself, “fan artists create artworks to share with other fan friends. Fandom generates systems of distribution that reject profit and broaden access to its creative works.”[1] Jenkins argument is that fans are in fact independent and creative consumers, and they reject the money and control driven motives of the culture industry in one sense by creating independent art and writing.

The rampant fan involvement, however, can also be interpreted as a further arm of the culture industry. Sam Caslin argues in her essay on the culture industry in a multimedia age that these fans are simply occupying a space within the culture industry. She argues that while multimedia has given fans new methods with which the fans “have attempted to gain some power within the mechanisms of modern cultural production and Western consumer society as a whole”, the culture industry “is able to inculcate fans into assembling themselves into markets.” Drawing on the works of Adorno and Horkheimer, she says, “the culture industry is no longer about the passivity of the audience.” Rather, now “The fan in particular now has multiple roles to play, from consumer to advertiser and, if their own desires are fulfilled, producer.”[2] Essentially her argument is that all these creations and activity by fans now serve as marketing and advertising, and as long as they stay committed in their devotion to the series they will remain that way. It is an expansion on the “pseudo-activity” that marked the token resistance within the system as described by Adorno, replacing the former ‘passivity’ of the consumer.[3] Any influence the fans have over the storyline or artifact they create will remain a part of the industry machine, and only if they question the actual method of creation will they actually challenge the creators.

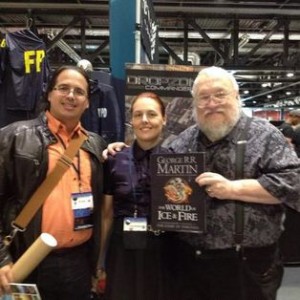

It is useful to compare these opposing views when we examine Game of Thrones, and in particular, two super fans Elio M. Garcia Jr. and Linda Antonsson. The couple first started reading the books shortly after the series began, and after being part of one of the very first forums, wanted to start a Game of Thrones game. To aid the game they started a fact-based website about the Game of Thrones world, Westeros.org. Soon the series exploded and the site became the number one destination for information on the Game of Thrones world. George RR Martin then started coming to them to fact check things for his writing, and now they have co-authored a book on the history of Westeros, the Game of Thrones world, with Martin.[4] On the surface, this justifies Jenkins, as their personal creation and additional take on the Game of Thrones world has ended up directly influencing the actual series. It shows they were able to “create works that speak to the special interests of the fan community.”[5] It was the ascension of fans to creator status that allowed them to directly influence the series as writers of the new book.

The journey of Garcia and Antonsson, however, doesn’t necessarily stand as evidence of fans subverting the culture industry. They didn’t create something new that was then adopted. Rather, they were picked by the creators of the series and simply made into producers. Before the book, Martin only came to them for fact checking – they weren’t influencing his plots.[6] Therefore Garcia and Antonsson are fulfilling the role described by Caslin where fans are elevated to ‘producer’ status. They haven’t changed the interests of the series with their ideas. Rather, it was decided their ideas would be the show’s next step. While Jenkins would see this as evidence for fan influence it is hard not to see it as the industry adopting the two fans as creators. They still have to operate in the pre-existing Game of Thrones world and among the same rules, only they are now responsible for the content. This can be seen in the criticism leveled at their work. Before, the criticism from other fans began a back and forth over a story that was open to be edited.[7] Now they publish a new piece of the Game of Thrones content and it is then criticized and debated, but since it isn’t a living piece but a mass-produced artifact, it won’t be changed. They’ve gone from fan to produce, and as Caslin would say, they’ve only changed their role in the culture industry.

So what is the verdict thus far? On the one hand, Jenkins is rather convincing when suggesting that fans express their independence by influencing the artifact itself. Certainly Garcia and Antonsson have a large influence on Martin and even write a part of the series with Martin. Additionally, Martin is known to have taken suggestions from fans before to make changes in the series when presenting pre-published work.[8] There, however, is the extent that the argument holds me. Caslin’s suggestion that the couple are simply being promoted from consumers to producers within the culture industry, and that no real change has occurred, is much more convincing as its hard to see how any of the fans’ actions change the interests or focus of the series. The idea that these fans were simply incorporated into the industry machine is furthered by the declaration by both the author and the show producers that fans will not influence their plot decisions.[9][10] Much of the alternative content created around Game of Thrones involves bringing back favorite characters who were previously killed, but as even as fans plead for their favorite characters back or for the killing to end the producers appear unmoved. This is actually significant because Game of Thrones represents the evolution of the culture industry in our multimedia age.

Game of Thrones reveals a new way in which the culture industry works in our day and age that illustrates why its fans are still very beholden to the industry. One of the phenomena that Game of Thrones has revealed is the way it’s reported by mass media. In the Internet age, we now are subject to constant dialogue where everyone has a platform to express themselves. This manifests itself in the way media outlets now report on Game of Thrones. The day after a show is inevitably full of recaps, but more and more the first headlines are not about the narration but about the reaction of the consumers. After various season five episodes a quick Google search returns dozens of articles similar to Mashable’s The Internet’s gut-wrenching reactions to the ‘Game of Thrones’ finale or Time’s The Problem with the Backlash to the Game of Thrones Rape Scene. [11][12] The media now focuses on the consumers’ reactions themselves, in particular their outrage and emotional outpouring that follows. Yes it manifests itself in videos and angry letters to the producers but every episode viewers come back once again, entranced by the show. The show has so perfected the emotional bond that half the entertainment seems to be the reaction of the consumer, yet they always lure them back for more.

It is from here that I come to the position that, in fact, the fan culture around Game of Thrones reveals consumers deeply entrapped in the culture industry. I still struggle to agree with Adorno completely; for example his claim that “Pleasure hardens into boredom because, if it is to remain pleasure, it must not demand effort… No independent thinking must be expected from the audience” suggests that he hapless consumer consumes with no effort and no intellectual creativity.[13] This, as Caslin mentioned, is no longer the truth. Consumers are now active participants and part of the spectacle themselves. Furthermore, they also contribute to the marketing of the series with their dedicated creations, though they never succeed in actually influencing the show to a degree that it actually subverts the aims of the culture industry. Rather the culture industry itself simply shifts consumers into other positions of significance if they deem it necessary or worthwhile. While I truly want to believe that these wonderfully diverse fan cultures are a method of breaking away from the pull of pop culture and the culture industry, I do not see any proof for it in Game of Thrones fandom. That would require something that not only influences the show but rejects its current form of creation at the same time. The fans detailed in this piece embrace the current form of creation. Instead I see a culture industry that is using our modern technological tools to further attract consumers and tighten its grip on our collective consciousness.

Works Cited

- D’Addario, Daniel. “Meet the “Game of Thrones” Superfan Who Knows Westeros Better than George R.R. Martin.”com. Salon, 28 Apr. 2014. Web. 18 Apr. 2016.

- Lutes, Alicia. “So, George R.R. Martin All-But-Confirmed a Big Ol’ Spoiler-y Fan Theory | Nerdist.”Nerdist. Nerdist, 14 Aug. 2014. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

- McCluskey, Megan. “Game of Thrones Showrunners Say Fan Criticism in No Way Influenced Season 6.”Time. Time, 1 Apr. 2016. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

- Colbert, Annie. “The Internet’s Gut-wrenching Reactions to the ‘Game of Thrones’ Finale.”Mashable. Mashable, 14 June 2015. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

- Young, Cathy. “The Problem With the Backlash to the Game of Thrones Rape Scene.”Time. Time, 21 May 2015. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

- Adorno, Theodor W. and Max Horkheimer. [1944] 1997.Dialectic of

London: Verso. - Caslin, Sam. 2007. “Compliance Fiction: Adorno and Horkheimer’s ‘Culture Industry’ Thesis in a Multimedia Age”. Fast Capitalism. Issue 2.2, 2007. Web. 18 Apr. 2016

- Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers: Television fans & participatory culture. New York: Routledge.

- Bialik, Carl. “These Authors Know The ‘Game Of Thrones’ Backstory Better Than George R.R. Martin Does.”FiveThirtyEight. ESPN, 18 Dec. 2014. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

[1] Jenkins, H. Textual poachers: Television fans & participatory culture. pg. 287

[2] Caslin, Sam. “Compliance Fiction: Adorno and Horkheimer’s ‘Culture Industry’ Thesis in a Multimedia Age”.

[3] Caslin, Sam. “Compliance Fiction: Adorno and Horkheimer’s ‘Culture Industry’ Thesis in a Multimedia Age”.

[4] Bialik, Carl. “These Authors Know The ‘Game Of Thrones’ Backstory Better Than George R.R. Martin Does.”

[5] Jenkins, H. Textual poachers: Television fans & participatory culture. pg. 287

[6] Bialik, Carl. “These Authors Know The ‘Game Of Thrones’ Backstory Better Than George R.R. Martin Does.”

[7] Bialik, Carl. “These Authors Know The ‘Game Of Thrones’ Backstory Better Than George R.R. Martin Does.”

[8] D’Addario, Daniel “Meet the “Game of Thrones” Superfan Who Knows Westeros Better than George R.R. Martin”

[9] Lutes, Alicia “So, George R.R. Martin All-But-Confirmed a Big Ol’ Spoiler-y Fan Theory”

[10] McCluskey, Megan “Game of Thrones Showrunners Say Fan Criticism in No Way Influenced Season 6”

[11] Colbert, Annie “The Internet’s Gut-wrenching Reactions to the ‘Game of Thrones’ Finale”

[12] Young, Cathy “The Problem With the Backlash to the Game of Thrones Rape Scene”

[13] Adorno, Theodor, Horkheimer, Max Dialectic of Enlightenment, pg. 137