In almost any action we take or place we go we are continuously making judgements of what is beautiful. We consider certain sounds smooth and melodic while others are brash and abrasive. Some visuals we find breathtaking while others are dull and lack character. We apply these judgements to people, architecture, music, and many other elements of our social settings that shape our culture. Often, such assessments of aesthetic quality appear to be made intuitively. But what guides this intuition? While complex biological factors may drive part of it, culture also seems responsible for at least some of our intuitive processes. Standards of beauty circulate within a culture, gaining acceptance. Those bred in the culture adopt these standards almost without thought or conscious choice. In identifying beauty, individuals appear to draw upon the ideas their culture has imparted upon them rather than reasoning their way toward their own definition.

Culture’s heavy influence on our perception of beauty raises the question of whether or not our distinction of certain aesthetics as beautiful is artificial. This question has provoked challenges to beauty as a valuable descriptor. An entire culture, namely Punk culture, has arisen around the rejection of the notion that certain aesthetics are superior to others. While the Punks have drawn attention to an interesting aspect of the way our culture manifests itself in our judgements, beauty remains a valuable concept. Specifically, if the underlying components of our notion of beauty have their basis outside of cultural standards, then the application of beauty to select aesthetics involves objective judgements. If not, then it is most logical to pursue the process the Punks have already begun in attempting to dismantle deep-seated cultural standards of beauty. It is difficult, however, to formulate a definition for beauty speaking in merely abstract terms. Formulating an objective definition of beauty is most easily accomplished in a particular context. To that end, we will examine manifestations of beauty in La Vie en Rose, a renowned song by French singer Edith Piaf.

La Vie en Rose is emblematic of many classic notions of beauty. As such, it serves as an excellent example in which to search for fundamental characteristics of beautiful aesthetics. Early in the song a range of soft, light, and harmonious sounds come together to create a setting for the music. In particular, there is a mixture of strings, notably a harp, followed by the entrance of a saxophone. This melodious opening, with its French rhythms, evokes notions of an old, esteemed French society. Piaf’s voice enters after 12 seconds; clean, clear, and consistent. Her pitch accentuates the classic French character of the song. Additionally, by singing in French, she adds a mystical, romantic nature to the piece. Naturally, these qualities of the song generate a seemingly beautiful aesthetic. Punk culture, however, takes issue with this intuitive assessment of a song such as La Vie en Rose as beautiful.

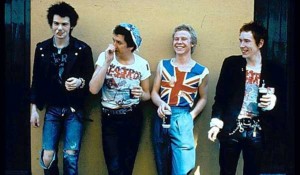

To believers in Punk ideals, a song such as La Vie en Rose is no more aesthetically pleasing than the vast body of more typical sounds. But how could this be? How could such an intuitively beautiful sound as Piaf’s singing not be logically superior to the sound of a pot hitting a pan? While not immediately obvious, the Punk argument provides a reasonable criticism. In Lipstick Traces, Greil Marcus describes the Punk Rock movement, particularly the development of the Sex Pistols, arguably the premier Punk band. In deconstructing the movement, Marcus sheds considerable light on Punk ideals. For example, one central goal of the Sex Pistols, and avant-garde individuals more broadly, was to generate cultural artifacts that were so repugnant that no one wished to appropriate them. In their only American tour, the band played almost exclusively locations in the south of the United States, a region where they expected their music to be rejected and misunderstood. From these actions, their purpose was clear. They wanted to cause believers in traditional beauty to recoil. Punks like the Sex Pistols were attempting to defy what they saw as society’s conventional ignorance of aesthetics. Part of where Punk identifiers, including members of the Sex Pistols, drew their views from was the evidence of differences in perceptions of beauty across different cultures and time periods.

This raises the question of what Punk defiance would look like in the context of La Vie en Rose. The smooth protracted hum that we associate with string instruments would be discounted as artificial. The crispness and clarity of the saxophone would be decried as undeservingly inflated in quality. Piaf’s voice would be met with skepticism. Why is her smooth, extended singing considered superior to the abrupt sound of Johnny Rotten’s voice? Rotten’s quivering manner of song which often walks a line between speech and shouting, and at times hardly qualifies as singing in any conventional sense, epitomizes Punk notions. It simplifies singing to a bare form of speech that almost any individual can create but that few wish to. It is difficult to distinguish quality in any usual manner between the shouting of one individual and another. In essence, Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols have distilled song down to a level where all can participate as equals, devoid of the divisive and stratifying qualities of traditionally “superior” sound. In doing so, Punks place the burden of proving the superiority of a singer like Piaf to performers like Rotten on those who serve as advocates of her talent, begging them to answer the question of what makes her superior. Punk identifiers would level similar criticisms of the glorious air of classic French culture that La Vie en Rose delivers as they would about Piaf’s voice. The elevation of classic French culture is, in their view, artificial. Punks argue that it is incumbent upon advocates of this elevation to demonstrate the qualities that mark it as superior. Dylan Clark makes clearer the overall Punk perspective by describing their view with respect to cuisine. Clark states “Punks, in turn, preferentially seek food that is more “raw”; i.e., closer to its wild, organic, uncultured state; and punks even enjoy food that has, from an American perspective, become rotten – disposed of or stolen. For punks, mainstream food is epitomized by corporate-capitalist “junk food”.” (Clark) Punks reject mainstream notions of beauty, and much else, implicitly arguing that they represent nothing more than arbitrary cultural overlays, introducing artificial constraints. To them, La Vie en Rose is on par in quality with the bitter, impassioned sounds of the Sex Pistols.

Having examined the Punk argument on beauty and having seen as an example how it would manifest itself in a Punk perception of La Vie en Rose, we can begin our search for a definition of beauty that illustrates the value in distinguishing beautiful aesthetics. To start with, the song title La Vie en Rose means “life in pink.” Pink is associated with that which is delicate and vulnerable, such as roses. The seemingly fragile hue fascinates us in the same way that, far back in history early humans were fascinated, with no cultural precedent, with other natural phenomena such as diamonds and eclipses. Human associations with pink and roses run deep. Historically, roses mean spring, meaning warmer weather, more food, the coming of a season of easier living. While it may seem simple to erase such associations from our minds, our appreciation for what Spring implies remains tightly tied to other biologically based appreciations. In essence, our association of warming seasons with the flowers that the weather heralds, while seemingly limited, is actually quite strong. Both signal the approach of easier seasons, an objective reality. The point to be made with regard to why we enjoy the sounds of the strings and the saxophone is even simpler. In La Vie en Rose, these instruments all produce sounds that are smooth and melodious rather than cluttered. Our enjoyment of the harmonies they produce demonstrate our general preference for order and its associated stability rather than chaos and uncertainty. This is in sharp contrast to Johnny Rotten’s biting, unpredictable voice and clashing chords. The comparisons do not end there. Much like the melodies that surround it, the French language that Piaf sings in is smooth and evokes the same indescribable, joyous feelings that accompany romance. The same reasoning applies to the sense of classic, esteemed Parisian culture that the song exudes. Paris is filled with endless avenues and alleys of ornately crafted buildings. Be it carefully created and colored four-story apartments, majestic museums built with triumphant pillars and stunning arches and filled with history’s finest art, the Eiffel tower itself, or the Champs Elysee and the convergence of the city’s streets. The city is the epitome of order, continuity, and meticulous craftsmanship.

Looking at the associations that La Vie en Rose generates in listeners in this way, it becomes clear that the qualities we appreciate in such songs are functions of more than random, culturally reinforced standards of beauty. Such “beautiful” songs draw upon ideas fundamental to most humans about what is appealing and what characterizes beauty. These characteristics arise from objective life-affirming artifacts. We prefer ordered entities to stochastic ones, melodies to clutter, and continuity to erratic occurrence. This leads us, at last, to a more concrete definition of what it means to be beautiful. To be beautiful is to have order, structure, harmony, or a similar such quality that provokes positive associations in observers which in turn evoke an appreciation for the entity at hand. This definition can be applied to the vast majority of aesthetics, but some will still escape the definition and can be explained by strange cultural standards that have arisen at some point and been cemented over time. The concept that beauty varies across cultures due to variations in cultural standards is, however, often exaggerated. For instance, in a study by a group of Professors from the University of Louisville and Chung-Yuan University, their research led them to conclude that “The consistency of physical attractiveness ratings across cultural groups was examined. In Study 1, recently arrived native Asian and Hispanic students and White Americans rated the attractiveness of Asian, Hispanic, Black, and White photographed women. The mean correlation between groups in attractiveness ratings was r = .93.” (Cunningham et al.) A variety of other measures of attractiveness across cultures taken in the same study led them to similarly high correlation values. This provides further support of the idea that concepts of beauty are frequently based on deeply biological associations and preferences.

With a definition of beauty that is based on the objective concepts of order and continuity, it becomes easy to realize how La Vie en Rose is a musical masterpiece. Most often, the features upon which our judgements of beauty are based are positive biological associations, fundamental preferences that are common to most humans. While the Punks make a compelling argument in acknowledging how perceptions of beauty seem to be intuitive assessments based on cultural standards, the existence of a definition that can capture what is beautiful in terms separate from cultural standards nullifies their argument. In identifying that there is something fundamentally human about the way we evaluate beauty, we have also made the case that beautiful aesthetics are worth pursuing. People appreciate them by sheer virtue of the way human perception is structured. And pursuing that which is basic to humanity is simply rational.

Bibliography

Clark, Dylan. “The Raw and the Rotten: Punk Cuisine.” Ethnology 43.1 (2004): 19-31. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. 16 May 2016.

Cunningham, Michael R., Alan R. Roberts, Anita P. Barbee, Perri B. Druen, and Cheng-Huan Wu. “”Their Ideas of Beauty Are, on the Whole, the Same as Ours”: Consistency and Variability in the Cross-cultural Perception of Female Physical Attractiveness.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68.2 (1995): 261-79. PsycARTICLES [EBSCO]. Web. 16 May 2016.

Marcus, Greil. Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.

Image Sources:

[1] http://joidartblog.com/en/2015/06/la-vie-en-rose-2/

[2] http://peel.wikia.com/wiki/Sex_Pistols

[3] http://mentalfloss.com/article/70991/15-monumental-facts-about-eiffel-tower