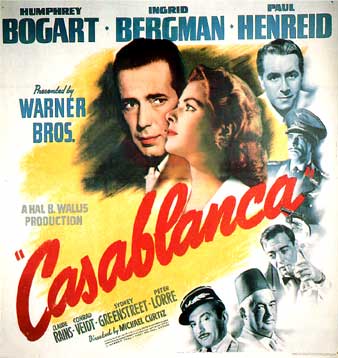

When Rick Blaine sees the love of his life, Ilsa Lund, at the door of Rick’s Café Américain in the 1942 classic film Casablanca, he is utterly dumbfounded. The beautiful woman he so loved, the woman who left him at a rail station in Paris years ago, has suddenly reappeared. The cinematic gaze of the camera follows Ilsa as she crosses the room on the arm of another man, just as Rick’s eyes do. It captures the onlookers gaping at her, marveling at just how dazzling she is. From the moment Ilsa enters the room, she is objectified: by the eye of the camera that with choice shots tracks her every movement, by every man in the saloon, and by every individual watching the movie.

The camera in effect turns every viewer into a restaurant customer seated at a table. And the eye behind that camera is a man. Not only is the cast of Casablanca almost exclusively male, but the creative minds behind the production are as well. In fact, the three screenwriters and director are all men, as are the cinematographer and film editor.[1] The plot and the historic timeline that it follows reflects stereotypically masculine concerns: war, duty to country, and freedom. Every decision-maker depicter, regardless of his political affiliation, is a man. All viewers, both male and female, are forced to see the world of Casablanca through the eyes of a man – the lens of a masculinized camera.

The gendered viewpoint that the film adopts is very much indicative of the time period in which it was produced. The manpower of Hollywood cinema, especially in the 1940s, cannot be overstated. The movie itself features three female characters in prominent roles (Ilsa, Yvonne, and Annina Brandel), and several other woman in ancillary roles.[2] The camera portrays these women literally in a different light than it does the men: they are more brightly lit, without shadows, and very often in soft focus. Both in her entrances into scenes and in her conversations with other characters, Ilsa maintains the attention of the camera; in several instances the lens remains fixated upon her even when she is not speaking.[3] When the female singer performs in the middle of the café, she is in the center of the camera’s shot.[4] She is illuminated, while the saloon audience is relegated to the shadowy periphery. The perspective of the film audience parallels that of the restaurant-goers: sitting in the dark, grouped around and staring at the singer. This double audience becomes a congregation of Peeping Toms who, from their seats hidden in the dark, watch a woman perform for their pleasure. The female character is implicitly objectified and sexualized; her function in the scene is to be looked at. Her thoughts and perspective are ignored.

This is the crux of Laura Mulvey’s argument as to why female characters are relegated to subordinate roles in film. She uses psychoanalysis to define three distinct “looks associated with cinema: that of the camera as it records the profilmic event, that of the audience as it watches the final product, and that of the characters at each other within the screen illusion.”[5] She contends that Hollywood’s editing style, known as continuity editing, harms us as viewers. It controls our viewing with its coercive close-ups, forcing us to focus on whatever the camera, and its operator, so choose. And since the chosen perspective is that of a male, Mulvey suggests that most films celebrate masculinity over the feminine, and portray women only as men perceive them rather than as they truly are. According to her, the only choice left to a woman watching such movies is “to identify with figures relegated to inferior status and silenced.”[6] If Hollywood productions such as Casablanca are so hopelessly misogynistic, is there an alternative?

One possible answer lies in the conception of the ‘woman’s film.”[7] Molly Haskell argues in her volume From Reverence to Rape (1973) that “female actresses of the 1930s and 1940s” had some roles that “offered images of intelligence, forcefulness, and personal power, far surpassing roles of actresses in later films.”[8] After its peak in the ‘30s and ‘40s, Haskell believes that “woman’s film” became less prevalent because men felt threatened by women holding positions of power, either within or without film.[9] Ilsa, the female lead in Casablanca, does not present the image of intellectual potency that characterize the women of Haskell’s “woman’s film,” nor does she wield any sort of power. She is even incapable of making her own decisions. When Ilsa professes her love to Rick and confides in him that she cannot decide what is best for her, she tells him: “You have to think for both of us.”[10] It is the man who then makes the choice of duty over love. Yvonne is a hapless one-night-stand who Rick simply casts aside without any concern. The newlywed Annina Brandel is just as powerless. She imagines that sexual favors are the only tools by which to change her destiny. When she pleads Rick to help her and her husband, the camera gravitates to her face. Film viewers are then able to see exactly what Rick sees: a beautiful young woman. Is this the reason he takes pity on her, helping her husband win money on a game of roulette? One cannot be certain, but the film certainly offers this possibility. All of the supposedly prominent female characters are essentially irrelevant and subservient to the male-driven plot.

What Haskell proposes as a replacement for Casablanca and the like is a variety of film that places women “at the center of the universe.”[11] Instead of their typical supporting role, actresses should be the leads in movies that have more inherently feminine concerns than the male intrigues apparent in Casablanca. Mulvey seems to agree with such an idea. She believes that a new type of feminist filmmaking “can… only exist as a counterpoint” to Hollywood convention.[12] In that sense, her work is a battle cry that is meant to inspire women to seize control of the culture that they consume. Casablanca is in almost every sense the polar opposite of every desire Haskell and Mulvey have for a feminist film alternative. The movie is made by men, about men, and for men. It is symbolic of what it means to be male: to be in power. Haskell and Mulvey see no need to analyze Casablanca and its equivalents, as they are simply indicative of a culture that is inherently male in character.

Some literary critics disagree with this notion of a separate “male culture.” In the mind of Lucy Fischer, discussion of women’s art should not be severed from everything that is male, but rather structured as an “intertextual debate” or “dialogue” between the two cultures.[13] As Myra Jehlen notes, “women cannot write monologues; there must be two in the world for one women to exist, and one of them has to be a man.”[14] Fischer thinks a film produced by a man can still on some level defy conventional norms, those norms being stereotypically male cinematic plotlines and power structures. So although a film like Casablanca may not deviate in the least from typical Hollywood masculinized film, it is still important to discuss it.

But the discussion of feminist cinematic concerns, even in the context of popular culture and the Hollywood filmmaking within it, still encounters issues of male domination that are apparent in Casablanca. Even as gender stereotypes have faded in modern movies, its manly cool continues to transfix, and that helps perpetuates a sexist perspective that men drive the plot and that women are merely interesting interludes along the road of a manly plot. Contemporary films still employ close-ups and choice POV shots that objectify the actresses they portray. Although women may play more active roles in cinema today than they did in 1942, they are still subservient to their male counterparts. The pattern of male domination is still apparent, and men still hold the majority of production positions. Women remain a distinct minority as executives, directors and cinematographers in the movie business. Only when they achieve that level of control will the scripts and the eye of the camera frame a different image of women. The powerful women who have risen to the top tier of the pop film industry demonstrate how the lens refocuses when a woman wields the camera.

[1] “Casablanca,” IMDb, May 18, 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0034583/.

[2] “Casablanca,” IMDb, May 18, 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0034583/.

[3] Casablanca, directed by Michael Curtiz (1942; Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Entertainment, 1942), DVD.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, ed. Douglas Kellner and Meenakshi Gigi Durham (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 403.

[6] Screening Genders, 18

[7] Molly Haskell, “The Woman’s Film,” in Feminist Film Theory: A Reader, ed. Sue Thornham (Washington Square, NY: New York University Press, 1999), 21.

[8] E. Ann Kaplan, “A History of Gender Theory in Cinema Studies,” in Screening Genders, ed. Krin Gabbard and William Luhr (New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press), 17.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Casablanca, directed by Michael Curtiz (1942; Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Entertainment, 1942), DVD.

[11] Molly Haskell, “The Woman’s Film,” in Feminist Film Theory: A Reader, 21.

[12] Lucy Fischer, Shot/Countershot: Film Tradition and Women’s Cinema (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 11.

[13] Ibid, 12.

[14] Lucy Fischer, Shot/Countershot: Film Tradition and Women’s Cinema, 12.