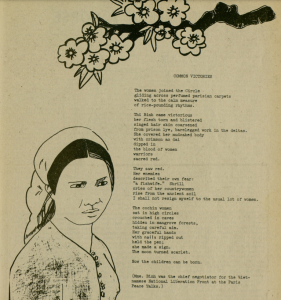

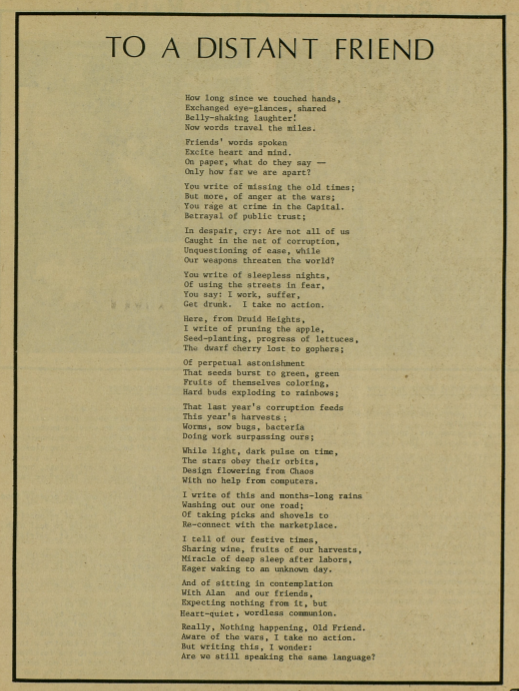

A poem, “To a Distant Friend,” by Elsa Gidlow, published in the 1976 issue of Country Women entitled “City~Country.” The poem discusses separations and divergences between city and country women, and the relationship between global politics and farm life.

Elsa Gidlow’s poem, “To a Distant Friend,” situated within Country Women’s 22nd edition on the divergence of the feminist movement between city and country landscapes, provides the perspective of a country feminist writing to a friend in the city. The poem discusses both the physical distance between these women, as well as their differences in values. The friend in the city is said to “write of missing the old times; / But more, of anger at the wars” (Gidlow 7). The urban friend has a clear political consciousness; their anger is so pronounced that they are corresponding with their friend in an attempt to make sense of this needless destruction. Even across the urban/rural divide, it is clear that an interest in global politics links these two women. However, the country woman seems more concerned with the natural workings of the world and partaking in a communal lifestyle: “here, from Druid Heights, / I write of pruning the apple, / Seed-planting, progress of lettuces” (Gidlow 7). Druid Heights was a poet’s commune owned by Gidlow and frequented by countercultural icons such as Allen Ginsberg and Neil Young (Silverstein). This retreat distanced Gidlow from the immediacy of anti-war efforts playing out in major cities at the time but allowed for her to remain grounded in the commune’s productive capacities. The alliteration present in these few lines suggests a methodical approach to this labor and a real connection to the land.

Gidlow writes about a fundamental linkage between the farm work that she is partaking in and the broader political landscape, asserting that “last year’s corruption feeds / This year’s harvests” (7). It is undeniable that the ramifications of U.S. global policy can be felt even in the most isolated of American communities. Climate change, megafarming, and the decimation of many rural communities in America can all be traced back to policy choices in the Capitol. The poem reaffirms the importance of the natural world to rural feminists. Gidlow ends the poem by stressing the role that communal living, working, and celebrating plays in the rural feminist’s political analysis, telling of “our festive times, / Sharing wine, fruits of our harvests” (7). It is through this communal labor that the rural feminist expresses her politics. Though a group of women farming in Northern California seems so disparate to global anti-war struggles, it is through living in cooperation and eking out a living wholly separated from state power that this rural feminist asserts her solidarity. This same idea is commented on in another article in the same issue of Country Women, with one woman proclaiming that “women’s communities can’t escape living their politics in their daily lives” (“City”). Gidlow’s poem exemplifies this idea that political meaning can come from land and labor itself. Through living and farming communally, rural feminists proclaim their independence from the capitalist, heteropatriarchal global order.

Works Cited:

“City Voices.” Country Women, no. 22, Country Women Editorial Collective, 01 Dec. 1976, pp. 13-16.

Gidlow, Elsa. “To a Distant Friend.” Country Women, no. 22, Country Women Editorial Collective, 01 Dec. 1976, p. 7.

Silverstein, Nikki. “Advocates Push to Preserve Historic Druid Heights Community.” Pacific Sun, Weeklys, 19 Jan. 2021, https://pacificsun.com/advocates-push-to- preserve-historic-d ruid-heights-community/.