It is all too easy in a project on second-wave feminism to fall into the trap of focusing on too narrow a perspective, so with this segment I hope to justify the treatment of the liminal body as an object of global interest. To do this, we look to several androgynous figures in mythology around the globe.

Starting in Greece, we look to the mythological figures of Tiresias and Iphis. Tiresias, according to myth, came across a pair of snakes in coitus, upon which he beat them with a stick. As punishment, he was transformed into a woman. Living as a woman, he became a priestess and had children. After seven years, he came across another pair of snakes, and this time stepped upon them, and was transformed back into a man. According to the most popular version of the legend, he was later called by Zeus and Hera as first-hand source in a debate over whether men or women had more pleasure in sex: when he responded that women did, Hera blinded him, but Zeus gave him as apology the gift of clairvoyance. Iphis, a figure in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, was born to two peasants who could not afford a dowry and so resolved to kill their child if he were not male. Iphis was born “female,” but his mother raised him as male so he would not be killed by his father. Eventually, when it came time for Iphis to marry, Isis miraculously transformed Iphis into a biological male. Both of these figures are remarkable in how they are clearly liminal figures without ever being in an androgynous state: their genders are always determined at any given moment, but are not temporally consistent.

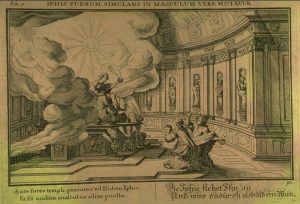

Tiresias moves to strike the snakes with his wand, for which he is punished by transforming into a woman.

“The male-looking Iphis transforms into a real male”—Isis transforms Iphis.

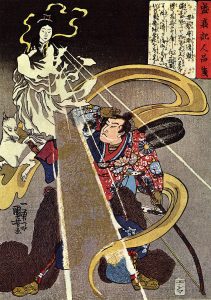

Next, we look to the figure of Inari (稲荷), one of the most important Shinto kami, probably best translated into English as “spirits.” Inari is the kami of foxes (among many other things), often portrayed as tricksters in Japanese mythology. Inari is variously depicted as male, female, or androgynous. Their messenger animals, foxes, are in mythology considered able to transform into human women in order to seduce men and have children.

This image shows Inari appearing as a woman to a soldier, with a white fox on their left.

There are many other examples of gender-ambiguous gods or mythological figures—for three interesting examples not covered here: the first people in the Dogon religion, the Aztec god Xochipilli, and the Sumerian Gala. However, rather than provide more examples of myths of liminality, it seems more of interest to provide examples of people actually considered to be non-male and non-female in non-binary gender systems, such as:

- Chilean (Mapuche) Machi: these religious leaders are considered to transcend the male-female binary, channeling different identities depending on the actions they are taking;

- Tahitian (Maohi) Māhū: this term, meaning “in the middle,” refers to assigned-male-at-birth people who act in an ambiguously feminine role;

- The great many identities coming under the compass of “two-spirit”—a term introduced in 1990 to refer to the variety of third-gender roles in North American native cultures, such as:

- Navajo nádleeh

- Mohave alyha

- Zuni lhamana

- Lakota wínkte

Although I cannot possibly cover all of these mythological entities as well as non-binary and gender variant identities, hopefully the idea that the liminal form is not restricted to “Western culture” has been justified.