Chrystos, a Menominee and two-spirit writer and activist, exemplifies several commonalities among Native feminist poets in the three brief stanzas of their poem, “I Walk in the History of My People” (“Chrystos,” 2021), which is included in the renowned feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women of Color. Among these themes is the recognition of the Native American’s body as exploited and corrupted. Chrystos establishes their own body as a manifestation of oppression of generations past, describing in the first line how they carry the “women locked in my joints / for refusing to speak to the police” (53). In the first stanza they list out the suffering that lives “In my marrow,” along with “women who walk 5 miles every day for water / In my marrow are hungry faces who live on the land the whites don’t want / In my marrow the swollen faces of my people who are not allowed / to hunt / to move / to be” (53). In three lines, Chrystos points to the dangers that Native Americans face in their communities, including hunger and scarcity of clean water, both of which result from the forced separation of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands and relocation to underserved and isolated areas.

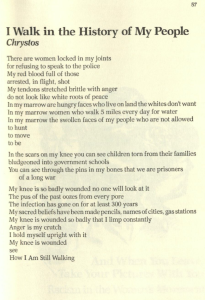

A scan of Chrystos’s poem “I Walk in the History of My People” from the second edition of This Bridge Called My Back published in 1983.

This injustice manifests in the physical and emotional psyches of Native Americans today. Indigenous activism is seldom featured in mainstream media and contemporary social justice movements. Chrystos speaks to the danger of this ignorance in the third stanza: “My knee is so badly wounded no one will look at it / The puss of the past oozes from every pore / The infection has gone on for at least 300 years” (53). In the first line they reference the massacre at Wounded Knee, in which over 300 Lakota people were killed by the US army (“Wounded Knee Massacre,” 2021), one of multiple massacres that are accepted as American histories and were celebrated as victories in their time. Now, the lack of these events from the education of American history contributes to the “infection” of the American colonial initiative to erase Native culture and life and robbing them of their right “to be” (53). Oppression also manifests in the appropriation of Native culture, the way it has been commodified and made into “pencils, names of cities, gas stations” (53). Chrystos highlights the burden of these oppressions carried by Native Americans and that every day they face dismissals of their very existence.

Along with intergenerational trauma, Native Americans inherit resilience from their ancestors. The continued existence of Native Americans is an act of resistance itself, a reminder that Indigenous life has survived despite centuries of attempted genocide: “My knee is wounded / see / How I Am Still Walking” (53). Chrystos empowers indigeneity by recognizing atrocities committed against their ancestors and thereby affirming their ancestors’ existence and success against all odds in protecting the future, in immortalizing Indigenous resistance through surviving and creating new life. Chrystos demands that we see how they continue to resist by existing proudly, fully, and unapologetically.

Sources:

Anzaldúa, Gloria and Moraga, Cherríe. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 2nd ed., New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color, 1983.

Anzaldúa, Gloria and Moraga, Cherríe. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., SUNY Press, 2015.

Chrystos. “I Walk in the History of My People,” This Bridge Called My Back. 4th ed., SUNY Press 2015, p. 53.

“Chrystos.” Wikipedia, 19 November 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chrystos.

“Wounded Knee Massacre.” Wikipedia, 4 December 2021.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wounded_Knee_Massacre.