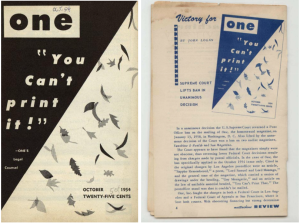

There is a long history of lesbian censorship and demonization in America, which is apparent through the reception and representation of queer stories in media. For example, ONE Magazine, which was known as the “first national, legally sanctioned organization dedicated to the promulgation of information on homosexuality,” had one of its earliest issues banned due to obscenity laws (4). The October 1954 publication of ONE magazine was withheld by the post office for including a short story called “Sappho Remembered”– an emotional portrayal of a woman reflecting on her identity. The most “sexual” act is a kiss, and yet the story rendered the issue as unfit for distribution. Although this ban was eventually reversed, it demonstrates publishers’ hesitation to acknowledge queer –and especially lesbian– relationships in mainstream media.

The October 1954 issue of ONE magazine (left), which was banned due to obscenity laws, is pictured next to an article titled “Victory for ONE” (right). The article announces the reversal of the post office ban and concludes that ONE had falsely been categorized as obscene and confiscated by the federal post office.

Mainstream media saw lesbians as a threat because they digressed from traditional heterosexual relationships and power systems. Tensions between lesbian feminists and their straight counterparts came to a boiling point at the Second Congress to Unite Women on May 1, 1970, which was held by the National Organization for Women (NOW). Although the term feminism became increasingly intersectional throughout the Second Wave Feminist Movement, the strong majority of speakers at the congress were middle class, straight, white women. Additionally, the First Congress to Unite Women, which was a year earlier, excluded prominent lesbian organizations, such as the Daughters of Bilitis. The co-founder of NOW, Betty Friedan, prompted a radical lesbian protest when she categorized lesbian feminists as a “lavender menace” in a speech (3). This term suggested that including lesbians in the feminist movement would subvert the authority of men since lesbians were often stereotyped as “man-hating” by their prejudiced straight counterparts. Lesbians played an essential role in the Second Wave Feminist Movement, so discounting their voices diminished their existence as well as their aid to the feminist movement.

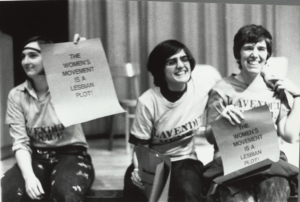

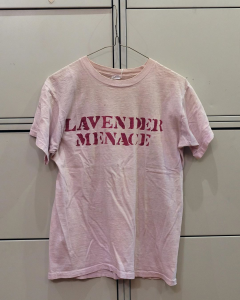

Lavender as a color was often associated with queer people, and has a deeper history than even the rainbow pride flag, which was designed in 1978. Some of the earliest references to purple correlating with queerness date back to Sappho’s poem fragments (1). However, it wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that lavender became seen as a symbol of gay empowerment. Purple fabric and clothing was used in the 1969 “gay power” march as well as the “Lavender Menace Rebellion.” After Friedan’s speech, radical lesbian feminists (or the radicalesbians) reclaimed the term “Lavender Menace.” The “Lavender Menaces” protested the Second Congress to Unite Women by wearing hand-dyed shirts and wielding hand-made signs proudly declaring themselves lesbians and self-associating with the color lavender. The women also took over the stage and microphones at the Second Congress to Unite Women and called out the prejudice and silencing being forced upon them within the feminist movement (3). This peaceful protest and demonstration of pride helped to ignite a radical lesbian movement and redefine feminism and the voices at the forefront of the movement.

Photograph from May 1, 1970 by Diana Davies depicting three women (Lita Lepie, Judy Cartisano, and Arlene Kisner) holding signs that say “THE WOMEN’S MOVEMENT IS A LESBIAN PLOT” and wearing shirts that read “LAVENDER MENACE.”

Hand-dyed Lavender Menace shirt worn in 1970, courtesy of the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

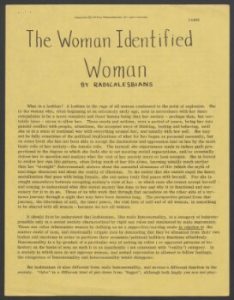

On May 1, 1970, the day of the Second Congress to Unite Women, the protesters also distributed a lesbian manifesto titled “The Woman Identified Woman.” The four-page manifesto was one of the most important documents in the creation of lesbian feminism. “The Woman Identified Woman” acknowleged the isolation that many queer women felt, and created a sense of unity while also making space for queer voices within politics and feminism. Additionally, the manifesto argued that lesbians are an extremely valuable asset to the feminist movement because they embody one of the core values of feminism — they are not defined or controlled by a male partner (5). In this sense, lesbians were seen as the “ultimate feminist.” “The Woman Identified Woman” also pinpointed the male gaze and patriarchy as the root of homophobia. The manifesto argued that when straight women find out that a woman is lesbian, then they fear that they will be viewed as a sex object because they have been conditioned by men to place themselves in that role:

[…] when a straight woman learns that a sister is a lesbian; she begins to relate to her lesbian sister as her potential sex object, laying a surrogate male role on the lesbian. This reveals her heterosexual conditioning to make herself into an object when sex is potentially involved in a relationship, and it denies the lesbian her full humanity. For women, especially those in the movement, to perceive their lesbian sisters through this male grid of role definitions is to accept this male cultural conditioning and to oppress their sisters much as they themselves have been oppressed by men. (The Woman Identified Woman, 1)

The Woman Identified Woman was a lesbian manifesto written by the Radicalesbians, and distributed on May 1, 1970 during the Second Congress to Unite Women.

The Woman Identified Woman was a major turning point for lesbian feminism and lesbian representation in media. In the subsequent years, many publications included a variety of lesbian media in an attempt to break down the mainstream censorship and façade that alienated queer women. On Page 16 of the first publication of Amazon Quarterly, a lesbian feminist literary magazine, they wrote: “Lesbian Woman has a message. The message is that Lesbians are people. This news will come as no surprise to the readers of Amazon Quarterly, but it may to the straight reading public to whom much of the book is addressed,” (2).

Material solely dedicated to creating space for oppressed groups was extremely valuable in helping to create a sense of unity. However, even within some queer-centered publications the authors and contributors addressed heterosexual society. The “straight reading public” was encouraged to read Amazon Quarterly by its publishers in the hope of breaking down biased preconceived notions and prejudices. A lesbian feminist literary magazine such as Amazon Quarterly would have portayed lesbians and queer relationships in a much more holistic and thoughtful manner compared to the messages mainstream media, which is why lesbian publications had the power to expand heterosexual perspectives on queer love.

Work Cited

(1) Hastings, Christobel. “How Lavender Became a Symbol of LGBTQ Resistance.” CNN, Cable News Network, 4 June 2020, https://www.cnn.com/style/article/lgbtq-lavender-symbolism-pride/index.html.

(2) Laurel, et al. “Amazon Quarterly.” Amazon Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 2, Amazon Press, Dec. 1973, pp. 1–76, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28032325.

(3) “Lavender Menace Action at Second Congress to Unite Women.” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/lavender-menace-action-at-second-congress-to-unite-women/.

(4) “One Magazine.” ONE Magazine | ONE Archives, 1 Jan. 1970, https://one.usc.edu/archive-location/one-magazine.

(5) “The Woman-Identified Woman / Women’s Liberation Movement Print Culture / Duke Digital Repository.” Duke Digital Collections, https://repository.duke.edu/dc/wlmpc/wlmms01011.