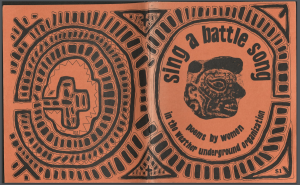

This is the cover of Sing a Battle Song: Poems by Women in the Weather Underground Organization. It was published in 1975 by the Weatherwomen as a testament to women’s struggles for liberation worldwide. Unabashedly raw, vulnerable, and poignant, this anthology captures a range and depth of women’s experiences that had never before been done by a Weather Underground publication.

For a group most remembered by their bombing campaigns, poetry may seem like an unexpected political and revolutionary tool. However, when put into the context of the radical feminist poetry and print movement, it makes sense that the Weatherwomen should add their own contribution and engage in the feminist tradition of poetry as an extraordinary political instrument.

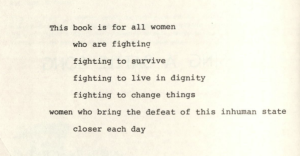

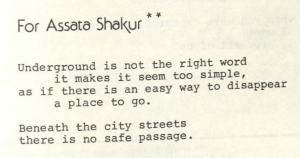

Dedication page of Sing a Battle Song written by the Weatherwomen in 1975.

Published in 1975, Sing a Battle Song: Poems by Women in the Weather Underground is a collection of poems written by women of the WUO. No poem has a named author nor does the anthology. Instead, the anthology centers not only on the collective voice of the Weatherwomen but the struggles of Vietnamese women and other women of color worldwide. The collection’s dedication to “all women / who are fighting / fighting to survive / fighting to live in dignity / fighting to change things” is intentionally widespread in an effort to call attention to the experiences of women across race and class divides.

Prior to the poems, Sing a Battle Song’s introduction cements the anthology’s aims and ideologies, building on the idea of “revolutionary sisterhood” first introduced in Prairie Fire. Namely, that the struggle for women’s rights is fundamentally an anti-imperialist struggle. In order to end the ways women are “dehumanized and exploited,” the institutions and forces that enforce these practices need to be destroyed. The introduction also offers the Weatherwomen’s stance on poetry and the purpose of publishing these poems:

We are not professional poets. Some poems were chosen for what they say, some for how they say it. Poems are for people to write, as they live; they are a way to share experiences and move others. We prepared this book of poetry as cultural workers, striving to create poems which are accessible to the people and responsible to the struggle (1).

At a time when the actions of women are policed and restrained, poetry offers a uniquely liberating form from which to express these experiences. In order to look at the way these poems reached across race, class, sexuality, and nation-state borders, I will be analyzing “Spider Poem,” “For Assata Shakur,” and “For Two Sisters.”

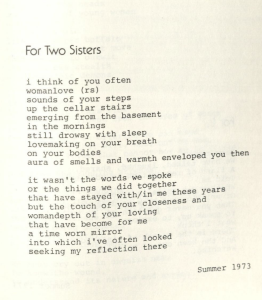

“For Two Sisters”

“For Two Sisters” paints a picture of love, security, and the simple beauty of female love.

“For Two Sisters” was written in the Summer of 1973 by an unnamed author. This is how it appears in Sing a Battle Song.

The use of all lowercase letters lends the poem an air of intimacy; it also feels innocent and young as if through the letter case the poem is trying to capture the very sensations of the love it describes. Speaking directly to the reader, the author writes that “i think of you often / woman love” (25). By addressing the reader directly, the poem feels almost like a love letter with the reader embodying her partner. She tenderly remembers the woman coming upstairs in the mornings, “still drowsy with sleep / lovemaking on your breath / on your bodies” (25). This description is sensuous and tender. Although the author is speaking about sex, it is not a graphic description. Rather, diction like “lovemaking” bathes the scene with feelings of domestic contentment. Yet, it is not the physical connection or even what the women say together that sticks with the author. Instead, it is “the touch of your closeness and / womandepth of your loving / that have become for me / a time worn mirror / into which i’ve often looked / seeking my reflection there” (25). The depth of their emotional intimacy, specifically her partner’s “womandepth” is what has kept her whole. Her desire to seek her reflection in the “time worn mirror” not only points to the desire to be seen the way her lover sees her but how another woman who loves her has seen her. Her special “womandepth” is an intrinsic part of her being, captured in the intimacy of this poem.

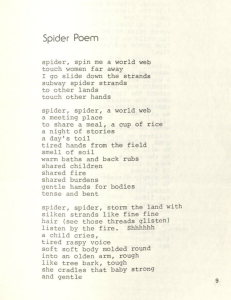

“Spider Poem”

This is an image of “Spider Poem” as it appears in Sing a Battle Song. It was written in November of 1974, no author is named.

Through the imagery of a spider weaving a web, “Spider Poem” calls attention to how women’s struggles are united and woven together in a way that transcends geographical location yet also recognizes the nuances of different experiences. The poem begins, “spider, spin me a world web / touch women far away / I go slide down the strands / subway spider strands / to other lands / to touch other hands” (9). The metaphorical “web” is what connects all women in their collective struggle and shared experiences. This opening stanza makes clear that the different segments of the metaphorical web are not separate, rather, women can access and learn about each other’s experiences if they “slide” or ride the “subway” strands. No experience is utterly closed off between women, even if they are different, there is this fundamental “web” connecting them.

Even though women are able to connect to each other’s shared experiences, the poem still acknowledges the differences in experiences, captured in the line: “We will meet / all of us /. women of every land / children on backs, in / arms, in shopping carts” (10). The three options of children “on backs” or “in arms” or “in shopping carts” highlight these differences. Yet even with these differences, whether they be class, race, or location, the author promises that “We will meet / in the center / make a circle / to discuss / to simply discuss / to simply discuss amongst / ourselves / our lives” (10). Here, the “center” is the union of these women, the place where their lives intersect so they may come together. The desire of sharing and power of “simply discuss[ing] our lives” as the poem expresses was a critical component of the Women’s Movement. Ending the isolation that trapped women in their condition alone was paramount to the success of the movement. As this poem highlights, the power of shared experience cannot go underestimated. In this way, power is what transforms the spider web into the final stanza’s “spidernet” (10). While webs are fragile, nets are strong, strong enough to “entangle / the powers / that bury / our children” (10). Nets can last generations. And, as this final line promises, the Women’s movement not only transcends place but also time. It is with a powerful worldwide network of women that true liberation and justice will be secured.

“For Assata Shakur”

This is the opening of “For Assata Shakur” written in June of 1973 as it is seen in Sing a Battle Song.

In the mid-1970s, poems and odes to Assata Shakur were not uncommon. Shakur was an activist with the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Movement, the anti-war movement, and other groups. On May 2nd, 1973, according to a recent Essence article, Shakur was “pulled over by the New Jersey State Police, shot twice and then charged with murder of a police officer” (Paula Rogo). She spent six and a half years in a maximum-security prison before escaping in 1979 to Cuba where she has lived in exile ever since. There is currently a two-million-dollar reward for her arrest. To this day, she remains, in the words of Essence magazine, a “revolutionary Black icon.”

“For Assata Shakur” is an ode to her life—a cry for her wrongful persecution and a celebration of her strength. The author speaks to Shakur’s dexterity as a political leader, telling her “You moved among your people / a gentle wind / Invisibly winding into their lives” (4). A “gentle wind” does not speak to any particular gentleness of character or action, but rather how Shakur’s work and activism encompassed all parts of the lives she fought for and how her work will continue to shape and mold people and the world for years to come.

Once Shakur escaped from prison, she immediately became a target of the U.S. government including the F.B.I. and state police. During this especially tumultuous time, she garnered much support from the outside as expressed by the poem’s speaker: “when they hunted you hard / I was a visible supporter, / working on another front.” The author, and thus the Weatherwomen as a whole, are unwavering in their support for Shakur. By including this poem, the Weatherwomen further affirm their commitment to freedom and justice for all women. Any woman’s fight for her liberation is their fight as well, and so when Shakur was captured, “I wept / for all of us” (10).

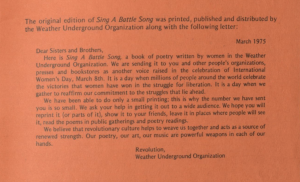

This is the final note to the readers of Sing a Battle Song on the inside of the back cover written by the WUO on March 8th, 1975 which is International Women’s Day. By ending the anthology with a note that places the anthology in the broader context of the Women’s Movement, the Weatherwomen solidify their commitment to the women’s liberation struggle and their commitment to ending imperialism worldwide.

On the back cover of the anthology is a final note to the readers of Sing a Battle Song. Addressing the note to the organization’s “sisters and brothers” includes men in the conversation and struggle for women’s liberation. This choice reinforces the WUO’s assertion that men themselves are not the problem, rather, it is the larger systems of oppression that strengthen and uphold the patriarchy. The WUO sent this anthology to bookstores and presses specifically on March 8th, International Women’s Day. A day where “millions of people around the world celebrate the victories that women have won in the liberation struggle. It is a day when we gather to reaffirm our commitment to the struggles that lie ahead.” This anthology, then, both lifts up and celebrates the incredible work done by women globally to end their oppression while still looking forward to all the work that remains. For this work to happen and achieve the global liberation of women, the Weatherwomen wrote: “We believe that revolutionary culture helps to weave us together and acts as a source of renewed strength. Our poetry, our art, our music are powerful weapons in each of our hands.” In this poetic way, militant feminism is not just about literal weapons or threatening violence or destruction. Instead, it is about powerful declarations of humanity, love, and strength that in the hands of a committed collective, have the power to truly change the world.

Works Cited

Rogo, Paula. “8 Things to Know About Assata Shakur and the Calls to Bring Her Back from Cuba.” Essence, 26 Oct. 2020.

Weatherwomen. “For Assata Shakur.” Sing a Battle Song: Poems by the Women in the Weather Underground Organization, edited by the Weatherwomen, Weather Underground Organization, pp. 3-4.

Weatherwomen. “For Two Sisters.” Sing a Battle Song: Poems by the Women in the Weather Underground Organization, edited by the Weatherwomen, Weather Underground Organization, pp. 25.

Weatherwomen. “Spider Poem.” Sing a Battle Song: Poems by the Women in the Weather Underground Organization, edited by the Weatherwomen, Weather Underground Organization, pp. 9-10.

Weather Underground Organization, editors. Sing a Battle Song: Poems by the Women in the Weather Underground Organization, Weather Underground Organization, 1975.