In many of the Weather Underground’s printed communications, one woman’s voice comes through loud and clear: Bernardine Dohrn. Dohrn was a member of SDS and one of the foundational members of the WUO; later, she would go on to become one of the group’s leaders. More than that, she was often the face of the entire organization. As Mona Rocha, author of The Weatherwomen: The Women of the Weather Underground, called her, Dohrn was effectively the group’s “high priestess” (82). In this role, she is highly visible in many of the group’s public messages, three of which include their “Declaration of War,” the report “Honky Tonk Women,” and the apotheosis of their political agenda, their manifesto Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism.

The WUO’s “Declaration of War”

By the time the organization disseminated their “Declaration of War,” written directly from the voice of Dohrn, much of the group had gone underground.

This is the “Declaration of War” heading from a 1970 issue of RAT, written collectively by the WUO. RAT Subterranean was a New York City-based underground newspaper that circulated from 1968 until 1970.

As the preface to the declaration summarizes, “Five months ago, most Weathermen disappeared from public view. […] Now, another Weatherman fugitive has been heard from—Bernardine Dohrn, ex-SDS activist and member of the Weather Bureau, Weatherman’s elite leadership group” (4). This communication served as an indication of where the group stood following the arrest of many of its members and the death of three members in an accidental explosion in a New York City Townhouse. The WUO explains that they “mailed copies to several of our friends and to several of our enemies,” RAT Subterranean, an underground New York City-based newspaper, being one of their friends.

The Declaration begins as such: “Hello. This is Bernardine Dohrn. I’m going to read A DECLARATION OF A STATE OF WAR” (4). This statement is powerful; although Dohrn writes that she will be reading the statement, it is still her name and voice that first come through. Further, as this is a written declaration and not in fact being audibly read by Dohrn, the word “read” really feels like “written.” While this declaration does not make any explicit links to the Women’s Movement, Dohrn’s power in the piece cannot be ignored.

“Honky Tonk Women”

At the WUO National War Council, Weatherwomen presented the document “Honky Tonky Women” outlining the group’s position on women’s liberation and articulating what their militant feminism truly meant. This document largely responded to the failings the group saw in the Second Wave movement:

For white women to fight for “equal rights” or “right to work, right to organize for equal pay, promotions, better conditions… ” while the rest of the world is trying to destroy imperialism, is racist. Those material improvements, like the rest of our privileges, are taken from the people of the world. These demands aren’t directed toward the destruction of Amerika, but toward helping white people cope better with life in an imperialist system (185).

This position aligned the Weatherwomen with many women of color and working-class feminists of the time who felt alienated by the superficial feminism coveted by largely white middle-class women. In this assessment, the Weatherwomen stress that striving to improve life under an “imperialist system” actually hinders true liberation as it fosters complacency within an inherently oppressive system. Instead, the Weatherwomen felt that

Our liberation as individuals and as women is possible only when it is understood as a political process—part of the formation of an armed white fighting force. Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, and the struggle to gain and use political power against the state is the struggle for our liberation (186).

Here, the Weatherwomen synthesize the purpose and goals of their militant feminism. By framing women’s liberation as a “political process,” the Weatherwomen implicate the entire political system and oppressive political systems in their struggles. Further, naming women’s liberation as political allows them to apply their militaristic practices to the cause. The WUO asserted that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” or militant action. Women’s liberation would only come from the destruction of imperialism which the WUO saw as only possible through militant means.

Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism

Cover of an early edition of Prairie Fire, first published in 1974. Prairie Fire was reprinted and distributed many times in places where radical activists met such as bookstores, college campuses, and food co-ops.

Published in May of 1974, Prairie Fire was the longest and most detailed account of the WUO’s ideology and strategy for revolution. It was not authored by one particular member of the group but rather reflected their collective views and experiences throughout their active years. Prairie Fire is dedicated to all “sisters and brothers who are engaged in armed struggle against the enemy. It is written to prisoners, women’s groups, collectives, study groups, workers’ organizing committees, communes, GI organizers, consciousness-raising groups, veterans, community groups, and revolutionaries of all kinds” (5).

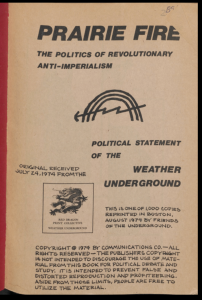

Opening Page of Prairie Fire featuring the copyright and circulation statement. This specific edition was one of “1,000 copies reprinted in Boston, August 1974 by Friends of the Underground.”

Prairie Fire tackled feminism in many of its sections, including the introductory ones, where Prairie Fire names what it sees as the current obstacles to revolution, one of which is sexism. The section reads:

The full participation and leadership of women is necessary for successful and healthy revolution. Revolutionary organizations must recognize the struggle for women’s liberation as a fundamental political revolution and must repudiate the intolerable backwardness of all forms of sexism. The development of the independent women’s movement as well as active struggle against the institutions and ideas of sexism are the basis for insuring that the revolution genuinely empowers women (12).

Compared to their founding document, “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows,” this articulation of the role of women’s liberation in the revolution is far clearer. It acknowledges the value of a separate women’s movement specifically focused on women’s issues as well as the necessity of having those same women involved in the revolution the WUO was attempting to incite.

In the section “Imperialism Means Sexism,” the WUO links the struggles of women in America to women of color (referred to as “Third World Women) in Vietnam specifically through the bigger system of imperialism. The WUO clearly states that the brutal impacts of U.S. imperial action are felt in countries the U.S. effectively colonizes. Under the guise of American exceptionalism and patriarchy, “women are murdered/tortured, sterilized/raped, stifled/crippled, owned/exploited” (87). In these ways, “imperialism enforces a systematic terror against women” that cannot be ignored. While fighting for revolution, the WUO could not “betray the struggle of women in general and our Third World sisters in particular. We embrace these struggles as our own and merge them with our own we create a basis for revolutionary sisterhood” (90). Again, the idea of “revolutionary sisterhood” and the emphasis on women’s liberation globally throughout Prairie Fire reflects how feminism truly was a central aspect of the WUO’s conceived revolution.

Works Cited

Rocha, Mona. The Weatherwomen: Militant Feminists of the Weather Underground. Jefferson, McFarland & Company, Inc, 2020.

Weather Underground Organization. “Declaration of War.” RAT: Subterranean News, June 5-19, 1970, pp. 4.

Weather Underground Organization. “Honky Tonk Women.” National War Council Packet, December 1969.

Weather Underground Organization. Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism. San Francisco, Communications Co., 1974.