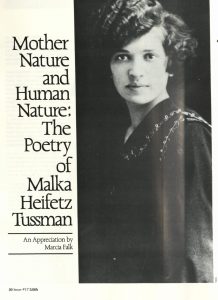

Seemingly in anticipation of the distress that might be felt at the “JAP Baiting” articles, the next piece in Lilith #17 is a powerful and uplifting exposé called “Mother Nature and Human Nature: The Poetry of Malka Heifetz Tussman.”  The author of this article is Marcia Falk, a Jewish educator and poet born into the baby boomer or post World War II generation. Falk celebrates Tussman as a midcentury Yiddish literary figure, activist, mother, and mentor. Tussman, born in the 1890s in Ukraine, wrote poetry and short stories in four languages including Russian, Hebrew, English, and Yiddish. Tussman only began to publish once she moved to Chicago in 1912. Falk first met Tussman at a Jewish arts festival in Berkeley, California, and afterwards began to translate Tussman’s poetry into English. The two women became friends and often exchanged poetry, letters, and recipes. In the summer of 1973, Falk lived in Berkeley with Tussman as they feverishly worked to translate eighty Yiddish poems that were later published as a chapbook (“Am I Also You?” published by Tree Books, 1977). The two women recognized the importance of preserving Jewish women’s literary legacy across time and place, embodying the very virtue of the intergenerationality that Jewish feminists in years to come would regard as necessary to the second-wave struggle.

The author of this article is Marcia Falk, a Jewish educator and poet born into the baby boomer or post World War II generation. Falk celebrates Tussman as a midcentury Yiddish literary figure, activist, mother, and mentor. Tussman, born in the 1890s in Ukraine, wrote poetry and short stories in four languages including Russian, Hebrew, English, and Yiddish. Tussman only began to publish once she moved to Chicago in 1912. Falk first met Tussman at a Jewish arts festival in Berkeley, California, and afterwards began to translate Tussman’s poetry into English. The two women became friends and often exchanged poetry, letters, and recipes. In the summer of 1973, Falk lived in Berkeley with Tussman as they feverishly worked to translate eighty Yiddish poems that were later published as a chapbook (“Am I Also You?” published by Tree Books, 1977). The two women recognized the importance of preserving Jewish women’s literary legacy across time and place, embodying the very virtue of the intergenerationality that Jewish feminists in years to come would regard as necessary to the second-wave struggle.

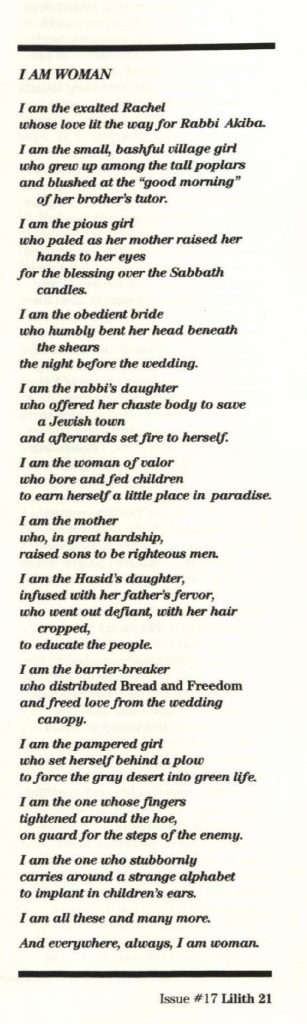

Tussman’s poem “I AM WOMAN” is reprinted on the first page of this article, boldly claiming Jewish womanhood in a series of statements that begin with “I am” and that emphasize the Jewish woman’s multifaceted nature. The poem begins “I am the exalted Rachel / whose love lit the way for Rabbi Akiba” (lines 1-2), grounding the piece around a traditional but celebratory view of Jewish women as Biblical and connected to male figures. Tussman moves through several verses declaring herself a “bashful village girl” excited by her brother’s teacher (3), a “pious girl” (7) who observes Shabbat, an “obedient bride” (12), and the “rabbi’s daughter” (17). But to Tussman, all of these characterizations contain a certain strength and grace: while these positions of power are dictated by patriarchy, and are most certainly informed by Tussman’s childhood as the daughter of a rabbi in a small Ukrainian shtetl, each of the verses end with a characterization of the sacrifices Jewish women have made that enable their communities and families to survive.  There is a turning point in the poem where Tussman writes “I am the mother / who, in great hardship, / raised sons to be righteous men” (24-26). Here, the woman’s power is not derived from the men in her life, but vice versa: part of her mightiness is the ability to raise “righteous” sons despite struggle. Their power originates in hers. After this line, the speaker of the poem declares herself an able rebel, a “barrier-breaker / who distributed Bread and Freedom / and freed love from the wedding canopy” (29-31). “Bread and Freedom” is a reference to Tussman’s work in Chicago’s anarchist-socialist political scene of the 1920s, where she advocated for economic justice and Marxism at the risk of deportation and arrest. This woman seems very different from the “obedient bride” who was exalted earlier in the poem, but is given equal weight, attention, and praise in Tussman’s poem. Tussman begins by honoring traditional women who have worked within the patriarchy and finishes by paying tribute to activist women who engage in the different work of activism. While neither of these types of women seem more privileged or powerful than the other, it is important to note that by finishing the poem with the activist woman, Tussman creates a developmental arc that begins within patriarchal norms and ends outside of such norms.

There is a turning point in the poem where Tussman writes “I am the mother / who, in great hardship, / raised sons to be righteous men” (24-26). Here, the woman’s power is not derived from the men in her life, but vice versa: part of her mightiness is the ability to raise “righteous” sons despite struggle. Their power originates in hers. After this line, the speaker of the poem declares herself an able rebel, a “barrier-breaker / who distributed Bread and Freedom / and freed love from the wedding canopy” (29-31). “Bread and Freedom” is a reference to Tussman’s work in Chicago’s anarchist-socialist political scene of the 1920s, where she advocated for economic justice and Marxism at the risk of deportation and arrest. This woman seems very different from the “obedient bride” who was exalted earlier in the poem, but is given equal weight, attention, and praise in Tussman’s poem. Tussman begins by honoring traditional women who have worked within the patriarchy and finishes by paying tribute to activist women who engage in the different work of activism. While neither of these types of women seem more privileged or powerful than the other, it is important to note that by finishing the poem with the activist woman, Tussman creates a developmental arc that begins within patriarchal norms and ends outside of such norms.

“I AM WOMAN” documents the development of a young Jewish woman of Tussman’s ethnic background, the development of her sense of womanhood, and her reclamation of her own strength.

Malka Tussman in LA, 1970s.

Tussman concludes by writing “I am all these and many more. / And everywhere, always, I am woman” (43-44). Perhaps Falk chose this poem to speak to Tussman’s importance within the context of Lilith andmodern Jewish feminism. “I AM WOMAN” fiercely reminds its audience that Jewish women are anything and everything they wish to be: powerful, spiritual, sexual, intellectual, and faithful. Falk ends her article with a copy of a letter sent to her by Tussman in the spring of 1975, near the end of her life. Tussman signs the letter with a note on the purpose of her writing, exemplifying the spirit of community so often conjured by poetry of the Second Wave: “And so my poetry is still travelling the endless road of ‘the Self’ to reach ‘the You.’ It knows no other road… Love, Malka.” Tussman, and her letter to Falk, embodies the fullness of Jewish feminist literature that sought to bridge generations, reclaim and redefine Judaism for women, and elevate people experiencing struggle everywhere.