Over the course of the five years that Elly Bulkin, Jan Clausen, Irena Klepfisz, and Rima Shore edited conditions together, they must have worked unbelievably hard. All four of them had full-time jobs and ongoing writing projects, but they still managed to do all of the extensive work of putting together a lengthy literary magazine every year without fail. Heresies had dozens of volunteers in their collective rotating in and out for every issue, and Quest had full-time paid staffers, but the editors of conditions managed to put together a peer magazine on their own, including everything from grant applications to advertising to printing. That these four women did all this without compensation is a testament to just how important they felt this work was, but when Irena Klepfisz left the magazine in 1981 “because of the demands of her paying job,” it is easy to empathize with her. No matter how important the larger cause is, anyone can get burnt out from too much office work.

A year after her departure, a Klepfisz poem titled “Work Sonnets” appeared in conditions: eight (conditions: eight, 1982, pp. 76-85). In it, Klepfisz reflects on the mundane reality of doing office work for a corporation in a low level position. This poem gives us a rare insight into a magazine editor’s life and attitude toward work after leaving the project, albeit through the lens of characters that are clearly distinct from Klepfisz, though she uses the first person. The poem is divided into three sections, each with its own experimental structure. The first section intersperses four stanzas describing the yearnings of elements of nature with diary-style prose-poetry describing scenes in a normal workplace. The second section adds flavor to the first section by taking the format of the brainstorming a writer might have done before writing the first section. Finally, the third section features a dialogue between two women, an inspired, aspiring writer seeking to do meaningful work to improve working conditions and an office worker who concludes that even if conditions improve, it won’t matter because her work still won’t be meaningful. Through these sections, Klepfisz wrestles with the possibility of leading a fulfilling life in an American office.

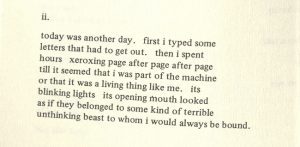

Excerpt from “Work Sonnets”

The first section of the poem explores the life of a female office worker with accounts of her frustrations with a Xerox machine, her power struggles with her boss, who is only ever referred to as “him,” and her relationships with her co-workers. At one point, the Xerox machine seems to come alive: “xeroxing page after page / till it seemed like I was part of the machine / or that it was a living thing like me” (76). This poem subverts the conventions of literature and poetry in many notable ways, including its structure and format, but also in its vocabulary. In these lines, “xerox” is used as a verb, allowing workplace vernacular to enter literature and at the same time symbolizing the narrator’s complete integration into a capitalist world of machines. In this world, humans are insulated from their environment as they become part of the company they work for, companies become the products they produce (it is a Xerox machine), and the names of the companies themselves become verbs, mere functions leading to ever higher productivity. There is no room for natural human life and relationships as everything bears the marks and logos of the techno-capitalist system that produced them. This human subordination shows up elsewhere in the poem, including when the retired receptionist’s hearing is “impaired from the headpiece she’d / once been forced to wear” (79), and the narrator shapes her schedule around the seemingly sentient Xerox machine: “when it overheated i had to stop while it / readied itself to receive again” (77). Not only is the narrator subject to the whims of her boss, who forces her to stay late, she is also subject to the whims of a mass-produced machine.

In section two, “Notes,” Klepfisz seems to switch perspective to the poet who composed section one as she designs a character and debates how she will portray her. Klepfisz seems initially to give us a third person description of the backstory and psyche of the narrator from section 1, whose previous jobs are listed. Klepfisz includes dialogue to illustrate her character traits. Then, the speaker of this section begins to debate how she will go about writing this character: “3rd person opens it [her worldview] up. But it would be too distanced, I think. I want to be inside her. Make the reader feel what she feels. A real dilemma” (82). Even though we don’t know the purpose of the section, the perspective, or how the writing is produced, Klepfisz does open a dialogue about how to portray others in writing, especially when writing from their perspective.

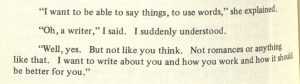

Excerpt from “Work Sonnets”

The third section of “Work Sonnets” takes the form of an existentially distressing dialogue between two women who work together about the possibility of fulfilling work. In this section, Klepfisz writes from the perspective of the woman who has no desire to be a writer and resigns herself to an unfulfilling career typesetting for others. The other woman, referred to as “she,” expresses her frustration with her job optimistically and says, “Anyone can do this. And I’ve always wanted to do special, important work” (83). She explains her idea of fulfilling work as socially conscious writing: “I want to write about you and how you work and how it should be better for you” (84). Initially convinced to reverse her earlier statement that “All work is bullshit” (84), the narrator of this section finds herself hopelessly resigned when she realizes that this idea of finding fulfillment in work still requires her to be part of a large, unfulfilled working class: “That certainly sounds good. Good for you, that is. But what about me… because I’m not about to become a writer” (84). This disappointment turns to anger as she accuses the aspiring writer of faking comradery with her now, only to later betray her by considering “that kind of work” to be beneath her. This dialogue illustrates how art and even the work of activist art can end up being exclusively reserved for the upper class, and more boldly asks a tough question without answering it: In a world of tedious office work where we can’t all become artists, how can we all find fulfillment?

Sources:

Klepfisz, Irena. “Work Sonnets.” Conditions: eight. issue 8, 1982. pp. 76-85.