Quest: a feminist quarterly was founded in 1974 with the goal of “seeking long-term, in-depth feminist political analysis and ideological development” (vol. 1, no. 1, p. [i]). Though they included poetry in every early issue, Quest always had a more explicitly political and analytical approach than Heresies, Conditions, or other feminist magazines of the time. In many ways, the side-by-side placement of dense articles about the mechanisms of political change and personal poems about real women’s experiences is emblematic of the Women’s Movement, embodying the slogan “the personal is political” in printed form. As a journal primarily of theory, Quest carved out its niche within the already niche market of feminist publishing. However, a downward spiral of financial troubles, overworked editorial staff, content cuts, and disorganization led to the decline and ultimate collapse of Quest in the early 1980’s. An examination of Quest’s later years evokes questions of the relationship between art and politics, the accessibility of theory, and ultimately what drives the feminist movement.

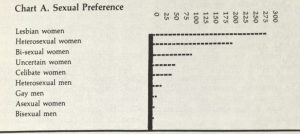

Quest’s story first becomes accessible to us beginning in the fall 1976 issue, when the editors began printing editor’s notes and letters from readers (Quest, vol. 3, no. 2). In that issue, we see that some of the readers of Quest are engaged in a heated debate about lesbian separatism. On one side, a reader wrote that she was not renewing her subscription because “I feel excluded by the increasing focus of your contributors on ‘heterosexist analysis’” (Quest, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 21). Another reader took an opposite stance, saying that “Quest is being very prejudiced against separatism,” and should “Name the enemy–men, their system, their everything– take a stand against it” (Quest, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 23). Although they don’t brand themselves as explicitly lesbian, it appears that was Quest’s reputation within the feminist community. In 1977, a reader wrote in to say, “I recently began my subscription to Quest, partly because I want to learn what my lesbian sisters are saying” (vol. 3, no. 4, p. 62). We don’t have access to demographics for the editors or contributors, but in the next issue Quest published the results of a reader survey, including a question about sexual orientation, that gives us a rare insight into the readership of a small feminist periodical in this period. There were about 275 lesbian, 100 bisexual, 200 heterosexual, and 50 uncertain women who responded to the reader survey, as well as less than 50 in each of the remaining categories: celibate women, heterosexual men, gay men, asexual women, and bisexual men (Quest, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 7). The Quest readership was diverse, but predominantly queer. It was a good place to have a debate about lesbian separatism, but when women stopped their subscriptions in order to make a statement about the issue, it was clear that the debate had become too politically divisive to be productive.

Results of a 1977 Quest reader survey

In addition to political reader debates, Quest struggled with reader comprehension. After apparently receiving feedback, the Quest editors published a note in 1976 saying that “We have often been told that Quest is abstract or ‘too hard to read’” (Quest, vol. 3, no. 2, p. [89]). The note voices these concerns that also appear in various letters from readers, and tries to explain and address them. It suggests that the reason that many contributors write in the style they do is because they “were trained, if at all, to write ‘essays’ and ‘papers’” and suggests that a more journalistic approach may be more accessible. However, the editors do express doubt about whether the same in-depth political analysis could happen in another style. They end by encouraging readers to submit manuscripts, noting that, “Our challenge, as feminists, is to find new ways to express our experiences and our analysis so that they aid us better in changing society” (Quest, vol. 3, no. 2, p. [89]). Despite the earnestness of this pledge to experiment with many different forms, it appears that nothing ever came of it. The editors printed this note, unmodified, in every issue until the magazine folded while continuing to print essays on theory. In fact, in 1981, they even decided not to print any more poetry, even though poetry had proven to be a reliable medium to express women’s experiences and push the movement forward. Clearly, Quest struggled to find an accessible medium for the kind of analysis it wanted to publish; however, any analysis of Quest’s struggles would be incomplete without looking at the practical realities of how the magazine was managed.

Cover art from 1976 with several distinct colors

Quest’s troubles with content, connecting with readers, and building community were worsened by a variety of practical factors. When they started, the editors of Quest were allowed to use office space and resources from the Institute for Policy Studies, but in 1977, they were forced out, and suddenly had to take on the costs of rent, equipment, and postage (Quest, vol. 3, no. 4). To accommodate this change, they had to cut down to two, and eventually only one paid staff member, even though they didn’t have the volunteer structure in place to handle the increased workload (Quest, vol. 5, no. 2). Consequently, they fell behind on their mailing schedule, testing the trust and patience of their readers while simultaneously increasing their costs as they lost their status as a class two mail client (Quest, vol. 3, no. 4). From 1978 to 1979, the staff took a full year publishing hiatus in order to try to restructure and solve the issues that were plaguing them. Many of the original staffers left and were replaced, often by multiple “contributing editors” (Quest, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 1). They even considered folding, but “decided the work of Quest had to be continued” (Quest, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 5). In order to decrease their printing costs, they lowered their page count, switched to a staple-bound binding and monochromatic cover art. On the fundraising side, they hired a fundraising consultant and looked for foundations that might be willing to award them grants, but found none, so they held a raffle that raised $1600. However, these efforts proved to be insufficient. The new staff published erratically rather than quarterly–only four times between 1979 and 1982. They found themselves overworked and disorganized, and faced worse mailing mishaps than ever before. In 1981, they sent a note to their readers explaining that “Quest has decided not to print poetry. Our decision was not based on any disregard for poetry or its power; but, rather, was based on taking stock of staff time, energy, and talents” (Quest, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 12). One reader wrote a particularly compelling note critiquing this decision and explaining the virtues of poetry and its power. She said, “I do not underestimate theory or analysis: I do not undervalue good strong prose writing or fiction: but nothing can reach inside a person and touch them and change them more than a good strong poem” (Quest, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 11).

Monochromatic cover art from 1981

By the time that reader letter was published, it was a moot point for Quest; the next issue proved to be their last before folding. No one can say for sure if another string of decisions could have allowed Quest to survive. Some of the events in their short history were just bad luck. Maybe a greater focus on poetry, art, and literature would have appealed to more readers. Perhaps it would have improved their eligibility for CCLM or NEA grants. Whatever the case, I do believe that the discussions Quest tried to spark and the content they published were important to have, and it was tragic to lose them.

Sources:

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 1, issue 1, 1974.

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 3, issue 2, 1976.

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 3, issue 4, 1977.

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 4, issue 1, 1977.

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 5, issue 1, 1979.

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 5, issue 2, 1980.

Quest: A feminist quarterly. vol. 5, issue 3, 1981.