Quest‘s “The Selfhood of Women” issue spotlights prose and poetry on female identity. In a preview of the issue, Quest writers explain, “the women’s movement is only as strong as the selves upon which it is built, a selfhood largely determined by our sex, our class, our sexuality, our race, our ethnic or geographic background” (Quest 1.2, 82). As we have seen through discussions of relationships and sexuality, many aspects of Second Wave Feminism tie back into home life; selfhood is no exception. Much of the publication centers around women’s identities as mothers, daughters, and sisters within the nuclear family. Karen Kollias, in her piece “Class Realities: Create a New Power Base,” discusses how many of the shortcomings of the women’s movement are rooted in the ways society defines the family. Experiences of those who do not fit into the “educated, white middle-class” label are often excluded from the movement and from the family definition (Quest 1.3, 29). Thus, she argues that excluding black and lower-class women from the feminist movement is a byproduct of their exclusion from the family identity. She proposes group identity as a means by which to resolve the exclusion of “othered” groups from both of these structures, but she acknowledges that caveats must come with how we define this powerful sisterhood: “feminism must allow for flexibility and work with the differences of women rather than ignoring them to get the similarities” (Quest 3.1, 35). As she characterizes different types of families – working class, working poor, lower class – and their struggles related to the movement, Kollias proves that the family and feminist movement are inherently intertwined.

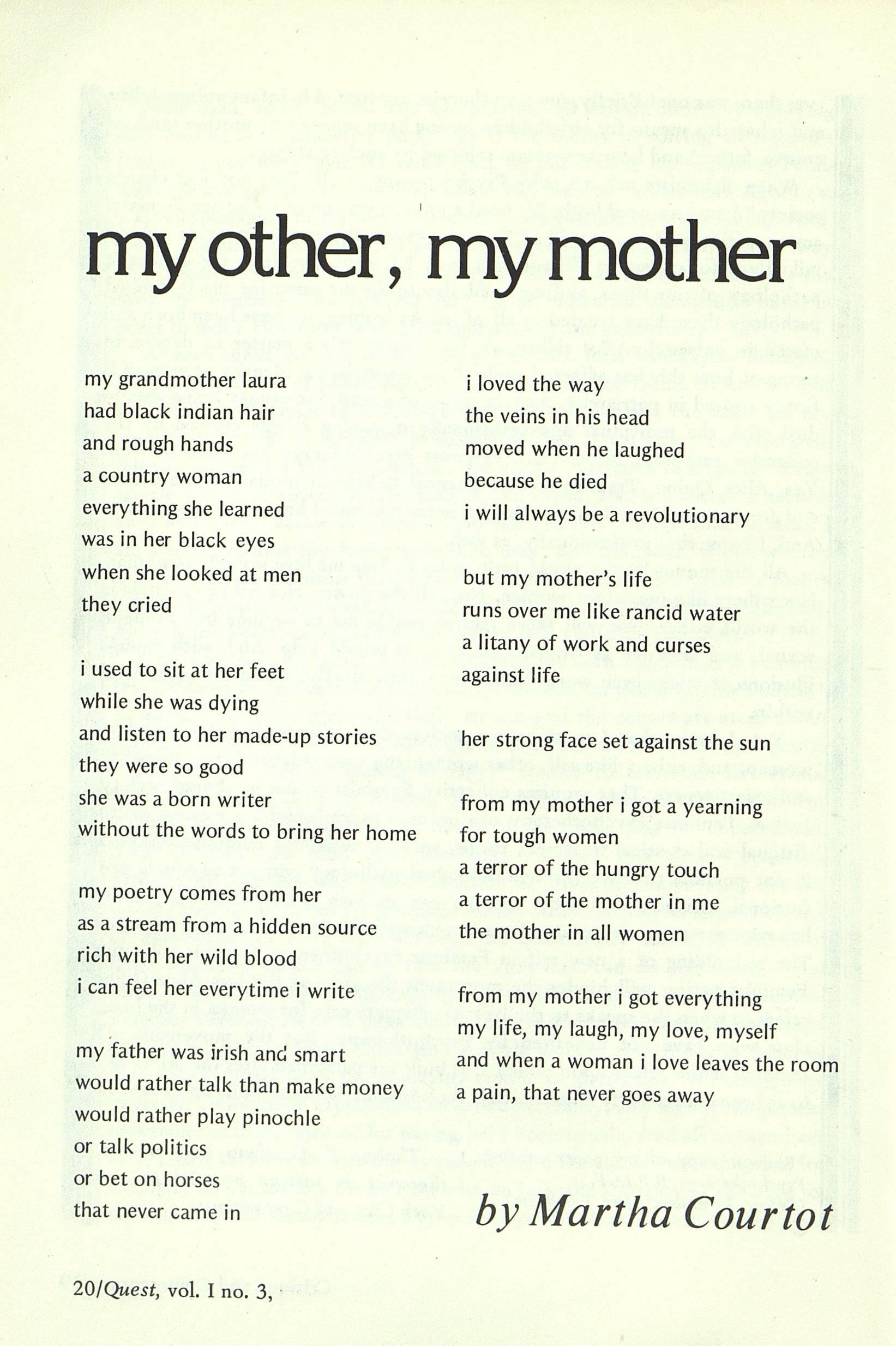

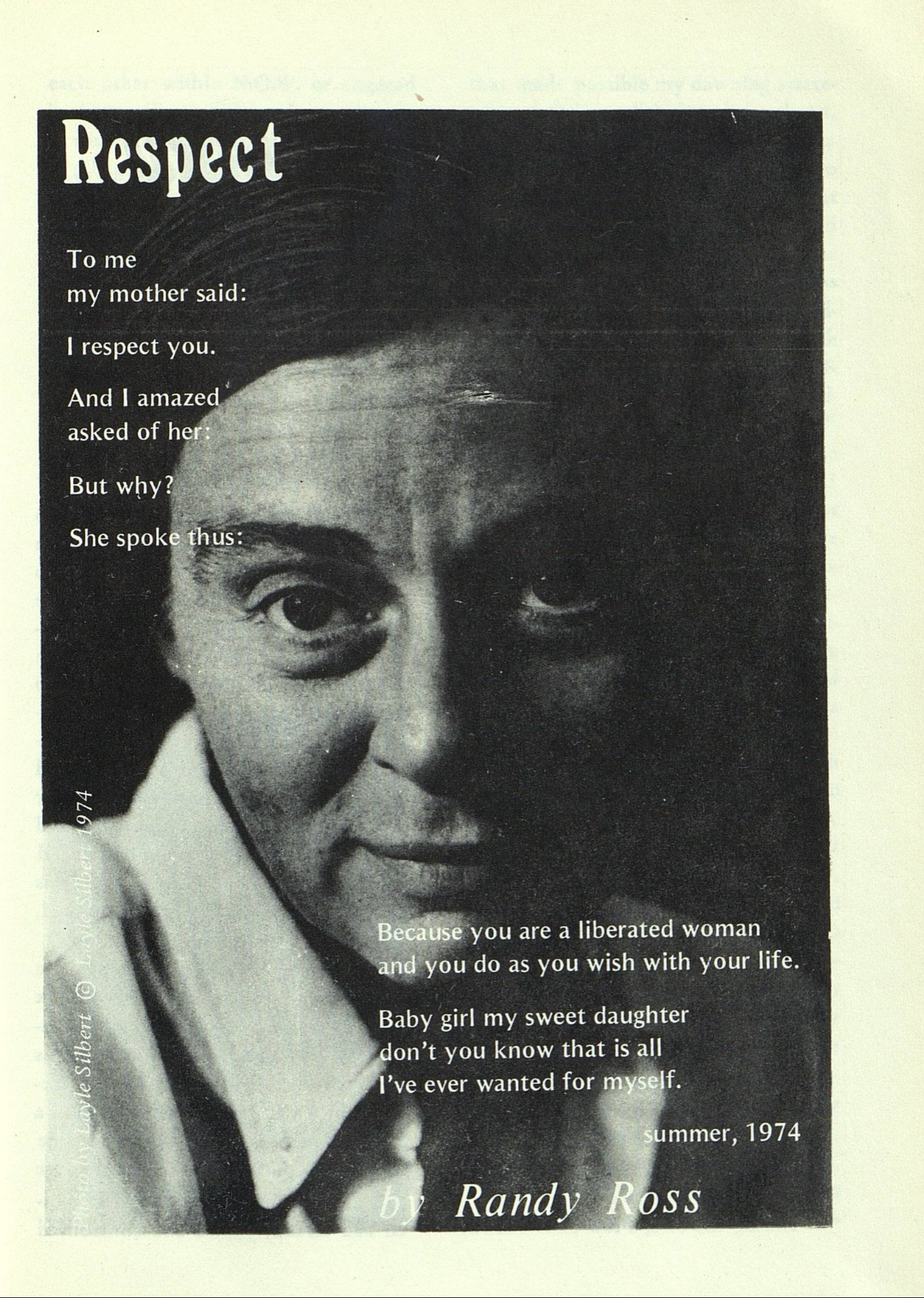

Martha Courtot was a lesbian, activist, mother, grandmother, and prolific poet. Her piece in Quest delves into some of these identities as she places herself in the context of her family. Her poetry comes from her grandmother and her being a “revolutionary” from her father (Quest 1.3, 20). In contrast to the comforting sentimental tales of her other relatives, she speaks of her mother differently. She writes, “from my mother i got…a terror of the mother in me / the mother in all women” (Quest 1.3, 20). She continues, “from my mother i got everything / my life, my laugh, my love, myself / and when a woman i love leaves the room / a pain, that never goes away” (Quest 1.3, 20). Courtot received both happiness and fear, love and pain from her mother. Courtot is afraid of the mother that lies within her and within all women. Yet she still knows, despite the pain her mother has put inside her, that she is a mirror image of her predecessor: “my other, my mother” (Quest 1.3, 20). This bond between mother and daughter is one frequently mulled over in feminist writings. Randy Ross in her poem “Respect” writes that her mother respected her “because you are a liberated woman and you do as you wish with your life” (Quest 1.3, 71). Generational progress could be seen within these interfamilial relationships. As her mother says solemnly, “that is all I’ve ever wanted to myself” (Quest 1.3, 71). Ross’ use of the present tense in “I’ve” solidifies that her mother still is unable to be free from the bonds of womanhood that constrain her. The periodical gives space for all types and strengths of these mother-daughter relationships to be explored, whether these bonds are riddled with “terror” or “respect.”

Lucia Valeska’s article, “If all else fails, I’m still a mother,” explores how the family structure has changed over time and how the once “stable family unit” of the nuclear family has “progressively disintegrated” (Quest 1.3, 56). “Here’s the deal,” the lesbian mother asserts. “The nuclear family is the result of an economic system which has  come to depend upon small, tight, economically autonomous, mobile units” (Quest 1.3, 55). The prospect of motherhood was an expectation for women. Many during the feminist movement sought to transform discussion of the possibility into just that: a discussion, rather than a given. Valeska discusses the differences in being “childless” and “childfree,” explaining that “the term ‘childless’ represents our society’s traditional perception of the situation…to be ‘childless’ still carries a negative stigma” (Quest 1.3, 56). “Childfree,” she explains is a term representative of the changing tides due to the work of feminists. Motherhood is no longer the end goal for women, the only means by which they can attain attain social acceptance and economic success. Still, Valeska concedes that, “clearly, with or without children, women are not free in our society” (Quest 1.3, 57). As is the structure of countless feminist articles, Valeska’s concludes with ways we must seek to reform these issues she brings to light: “We must develop feminist vision and practice that includes children. We must allow mothers and children a way out of the required primary relationships of the nuclear family” (Quest 1.3, 63). Her powerful piece so clearly and convincingly demonstrates that if “all else fails,” she is more than just a mother living within the constraints of the toxic nuclear family.

come to depend upon small, tight, economically autonomous, mobile units” (Quest 1.3, 55). The prospect of motherhood was an expectation for women. Many during the feminist movement sought to transform discussion of the possibility into just that: a discussion, rather than a given. Valeska discusses the differences in being “childless” and “childfree,” explaining that “the term ‘childless’ represents our society’s traditional perception of the situation…to be ‘childless’ still carries a negative stigma” (Quest 1.3, 56). “Childfree,” she explains is a term representative of the changing tides due to the work of feminists. Motherhood is no longer the end goal for women, the only means by which they can attain attain social acceptance and economic success. Still, Valeska concedes that, “clearly, with or without children, women are not free in our society” (Quest 1.3, 57). As is the structure of countless feminist articles, Valeska’s concludes with ways we must seek to reform these issues she brings to light: “We must develop feminist vision and practice that includes children. We must allow mothers and children a way out of the required primary relationships of the nuclear family” (Quest 1.3, 63). Her powerful piece so clearly and convincingly demonstrates that if “all else fails,” she is more than just a mother living within the constraints of the toxic nuclear family.