One of the most well-known and oft-quoted fragments of text in history must be the first three-line poem of Genesis (quoted here in two translations):

“God created humans in his image,

In his image he created him,

Male and female he created them.” (Alter translation)

“So God created man in his own image,

in the image of God created he him;

male and female created he them.” (King James Version)

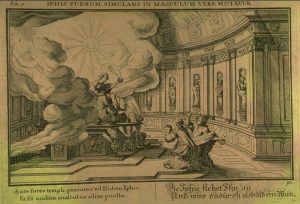

If “male and female” were created both in God’s image, does this imply that God is a liminal form? Certainly he is not traditionally depicted as such—throughout the canon of “western art” He is shown as an old man. However, the picture gets more complicated when one considers also the traditional images of angels: neither male nor female, they are usually shown as perfectly androgynous “beautiful” forms.

Angels in the Renaissance were usually depicted androgynously, to show their divine beauty. This may also speak to them being intermediary between humans and the divine, as the bible seems to offer evidence for a liminal perspective of God.

Through the Old Testament canon, God is usually not present as such, but rather appears as an “angel of the presence” (Isaiah 63:9). Through this insight, we see that God’s presence can be naturally interpreted as androgynous in accordance with Christian tradition.

In Jewish tradition, much more thought has been given to the liminal God. In Kabbalah, a traditional form of rabbinic esotericism, God, or “Ein Sof,” is shown as a series of 10 interconnected aspects—the Sefirot. Together, the Sephirot form a complete image of God; they are all crucial aspects of Him. It is no coincidence that roughly half of these “emanations” are considered “feminine”—most relevantly, beauty.

This gives us a very interesting look into liminality—androgyny is often seen as superhuman, divine, or perhaps indescribable beauty. Likewise, those who seek to defile this divine form are held in the lowest possible regard. For instance, Lot offers to let the men of Sodom and Gomorrah rape his two daughters in order for them not to assault the angels of the Lord. The men refuse, attracted presumably by the angels’ divine beauty. This immediately proceeds the two cities’ absolute destruction at the hands of God.

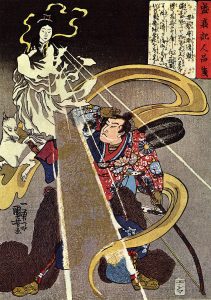

It should come as no surprise, then, that unholy beings like demons might have these traits too, seeing as such unholy beings are often seen as warped or distorted versions of holy beings. For notable examples, many demons of Abrahamic traditions are taken from idols of other cultures, such as Ba’al. Idol worship is sinful in the bible because it is treating a creature that is not God as if it were God, and thus there must be a disturbing parallel between the traits of an unholy idol and the traits of a holy being. For another example of this, look to Revelations, in which the Antichrist is mistaken for the second coming of Christ.

Esoteric faiths often borrow as higher entities such idols (or such demons, depending on one’s point of view). Thus it is only natural that esoteric higher entities often have warped versions of the features of God and His angels. In particular, for the purpose of this project, their androgyny.

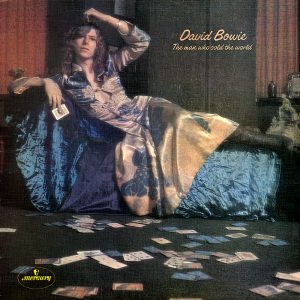

Some Tarot decks, for example, adopt as its highest trump card an image very reminiscent of that of an angel, most notably the iconic Rider-Waite deck. The card is full of imagery from Revelations, so a figure representing duality unified is only natural.

The figure of The World, the final trump of the tarot deck, shares much of the symbolism of Baphomet. It floats in a void surrounded by the four living creatures. Upright, it represents completion, perfection; in reversal, stagnation, suspension.

For a darker example, we look to the image of the Sabbatic Goat, traditionally associated with the demon Baphomet. Originally invented as the demon the Knights Templar were accused of worshipping, Aleister Crowley’s esoteric faith took it on as a higher power. It shows a unification of beast and man, man and woman, up and down, and dissolution and reconstitution. It is in this depiction of a liminal form that we begin to see not the supposed “divine beauty” of androgyny, but rather a kind of cosmic horror and lack of understanding, reminiscent of Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones.

Baphomet, with arms pointing up and down, angelic wings paired with demonic horns. On its arms are written the words “solve” and “coagula”—”dissolve” and “coagulate.” Baphomet is depicted with a simultaneously male and female form.

This is undeniably poetic: the physical representation of the unification of opposites itself has two opposite interpretations, one of superhuman beauty and one of grotesque unnaturality—two sides of the same coin.