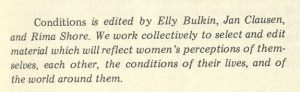

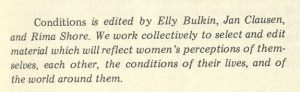

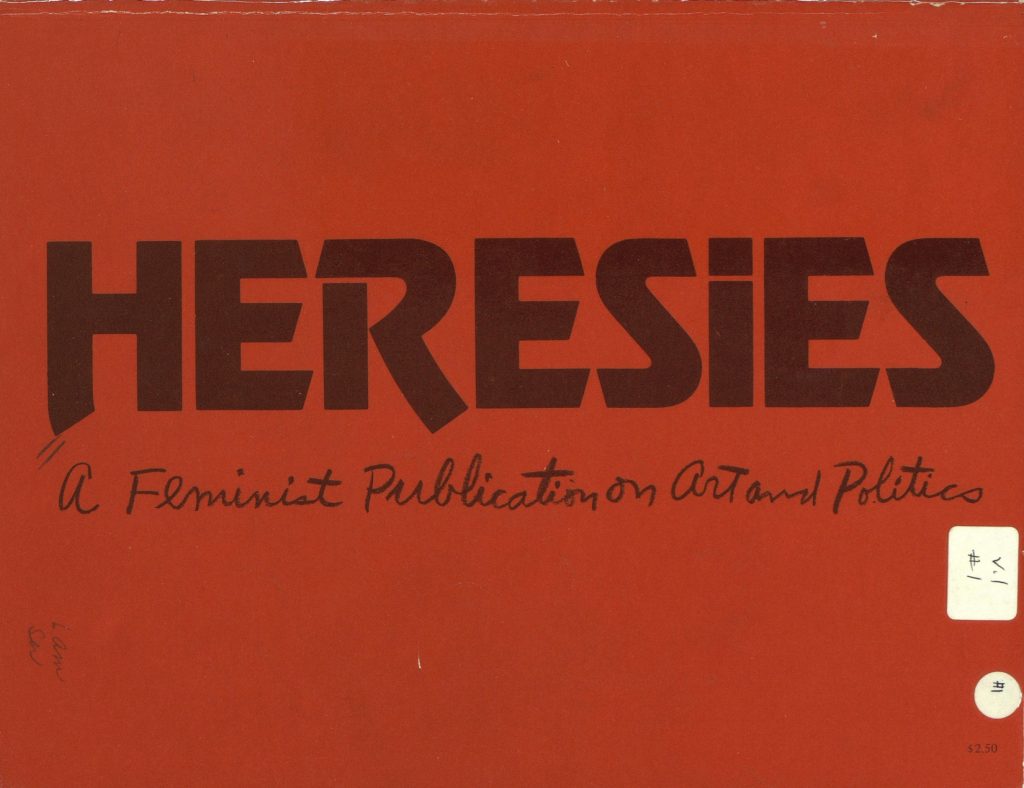

In contrast to Heresies’ broadly-based editorial collective, conditions magazine relied on the same four women to produce each issue, which led to challenges as the magazine aged and its editors felt the strain of years of uncompensated volunteer work in addition to their full-time jobs. Conditions was founded in 1976 by Elly Bulkin, Jan Clausen, Irena Klepfisz, and Rima Shore as “a magazine of writing by women with an emphasis on writing by lesbians” (conditions: one). Conditions’ story of editorial turnover and endangered governmental grants raises questions of how feminist art should be funded and what editorial structures will endure in challenging times.

Editor’s Statement that appeared in conditions: one

In their first couple of years, conditions experienced moderate success publishing fiction, interviews, book reviews, and a good deal of poetry, including the editors’ own work, in biannual book-length collections. However, the publishing business is risky and the editors had no significant backers, so by 1978, they were forced to implement a price increase so as not to increase the personal debt they had gone into to start their publication. Fortunately, they received a grant from the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM) in the same year, which eased their financial situation. However, they still expressed to their readers a desire to make sure grants were not essential to their bottom line, for “we do not believe that any lesbian-feminist organization can rely on grants as a continuous source of income” (conditions: four, p. [vii]). This note in conditions: four would be the beginning of an exciting saga that would play out over the course of the next six years.

After their first note to their readers in 1978, conditions received a major boost from the unprecedented success of conditions: five, the black women’s issue. As one of the first major anthologies of black feminist literature, conditions: five represented a major step forward for feminist publishing. Readers were clearly hungry for this kind of content, as it sold four times as many copies as any previous issue, with print runs totalling 10,000 copies (conditions: six, p. [vi]). This issue also gave the regular editors a break, as it was guest-edited by Lorraine Bethel and Barbara Smith. However, one successful issue did not insure the future of the magazine, and 1980 hit conditions as hard as anyone else.

After their first note to their readers in 1978, conditions received a major boost from the unprecedented success of conditions: five, the black women’s issue. As one of the first major anthologies of black feminist literature, conditions: five represented a major step forward for feminist publishing. Readers were clearly hungry for this kind of content, as it sold four times as many copies as any previous issue, with print runs totalling 10,000 copies (conditions: six, p. [vi]). This issue also gave the regular editors a break, as it was guest-edited by Lorraine Bethel and Barbara Smith. However, one successful issue did not insure the future of the magazine, and 1980 hit conditions as hard as anyone else.

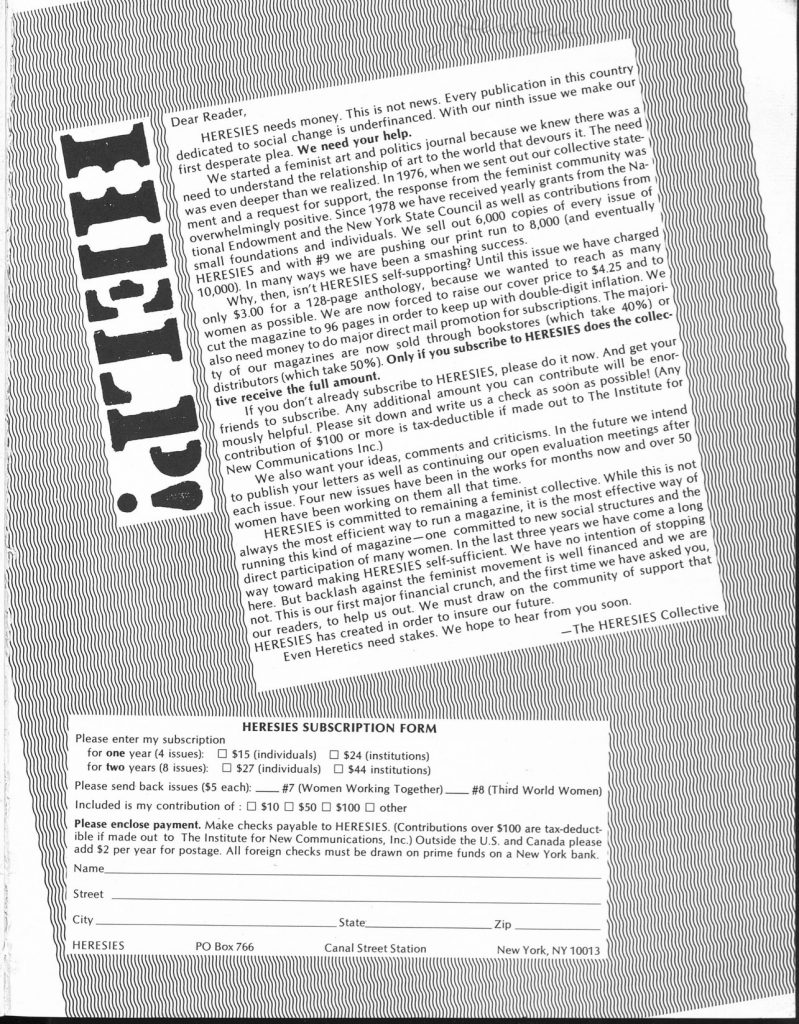

In conditions: six, the editors provided a rare, in-depth look at the finances of a small publication. In 1979, their total expenses were $18,095 for the combination of printing, typesetting, promoting, distributing, and compensating contributors for conditions: five, as well as paying off the loans they had taken out to start the magazine. Receiving $7,722 of grants that year from the New York Council on the Arts, the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM), and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), they were just barely able to break even (conditions: six, p. [vi-viii]). Much like Heresies was doing during the same period, conditions tried to address their tenuous financial ground by increasing their distribution and cover price, and asking a larger portion of their readers to become subscribers, although it is worth noting that unlike other contemporaneous publications, conditions did not decrease its page count at this time. However, conditions was a much smaller publication than Heresies, with print runs only totalling 3,000 copies per issue to Heresies’ 8,000, which made it much more difficult for conditions to become self-sustaining and forced them to rely more heavily on grants. Because of their heavy reliance on grants, it’s worth looking at the governing bodies that awarded grants to small magazines in this time period, specifically the CCLM and the NEA.

The National Endowment for The Arts first began under Lydon Johnson in 1965, largely as a response to cold war era thinking that the United States must work to be culturally superior to the Soviet Union and the nations it claimed leadership over (Levy, 108). From its inception, the NEA was a battleground between the political right’s desire to emphasize mainstream art at the expense of marginalized groups and the left’s desire to emphasize artists at the margins of society, presumably including the lesbian and feminist writers who wrote for conditions (Levy, 107). Both the total annual budget and the distribution of that budget were and continue to be subject to party politics at the NEA and the federal government that oversees it. Two years after the establishment of the NEA, members of its senior staff created the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM) with the goal of aiding noncommercial literary magazines and the individual artists and writers who contribute to them (Uchmanowicz). The CCLM had a budget of $125,000 to support thirty-eight magazines in its inaugural year, and by 1980 that budget grew to almost half a million dollars, with most of that money coming from the NEA (Uchmanowicz). In the intervening years, women entered the CCLM at every level, so that in 1976, four out of the seventeen CCLM board members and consultants were women, a marginal victory to be sure, but probably still better than most governmental boards at the time (Uchmanowicz). However, in 1980 Reagan was elected, and funding for the arts was sure to be cut during his administration.

Early in the Reagan administration, the NEA was forced to withdraw almost all of its financial support for the CCLM, forcing them to seek out funding from private interests (Uchmanowicz). Meanwhile, the value of the NEA itself, which had been rising steadily since its inception, held steady throughout the 80’s at around $160 million (NEA Annual Report 1987). The CCLM did manage to find private funding sources in the 80’s, including Exxon Corporation, the New York Times, the Mobil Foundation, and the Liz Claiborne Foundation, but Nicholas Nyary, the then executive director, found the literary climate of the decade “troubling,” and expressed hopes that magazines would be able to survive until a more favorable time (Uchmanowicz).

The NEA also came under fire in the media for cutting off funding to the CCLM. An opinion piece by the assistant director of literature at the NEA appeared in the New York Times in 1983 in response to claims that the lack of Endowment funding to the CCLM was “likely to mean the death of many of the shoestring operations” (Macarthur). Assistant Director Macarthur argued that the move to cut off funding to the CCLM was actually a maneuver to cut out an unnecessary middleman that would allow the NEA to give more money directly to literary publishers (Macarthur). While it is true that the NEA gave a significant amount of money ($825,000 in 1983 according to Macarthur) to small publications, including grants to both conditions and Heresies, Macarthur offered no evidence that they would balance out the funding they were no longer giving to CCLM and no justification for why they would no longer support the CCLM. While officials like Macarthur may have tried to hide it, Reagan’s 80’s were a time for governmental budget cuts, especially in the arts.

In light of this, we can truly see how deeply precarious conditions’ situation was entering the 80’s relying on government grants. The 1981 fiscal year for conditions looked very similar to 1980, with expenses totalling $18000 and $8000 of grants keeping them afloat, but the editor’s note in conditions: seven expressed great concern Reagan-era budget cuts and legislation, especially the Family Protection Act, which would, among other things, cut off all federal funding for lesbian and gay organizations (conditions: seven). If the bill had passed and conditions could not seek funding from any federal sources, it is difficult to imagine the magazine would have survived. Even without broad-based legislation, conditions’ federal funding was not secure; in 1984, their grant application to the NEA was rejected because “the magazine seems to emphasize lesbianism more than literature” (conditions: ten).

Editor’s Statement in conditions: seven with only 3 editors listed

Conditions’ instability due to insecure funding sources was worsened by editorial turnover. Most small magazines had some editors and staff leave during this period. It was, after all, a period of change for the Women’s Movement. But with only four editors to begin with, editorial turnover became an existential crisis for conditions. The first of the original four editors to leave was Irena Klepfisz. In the conditions: seven editor’s note, we learn that Klepfisz decided to take a “partial leave-of-absence from the editorial collective because of the demands of her paying job” after conditions: six, and by the time conditions: seven was published, she had decided to leave the magazine entirely (conditions: seven). Following conditions: seven, the remaining editors took a publishing hiatus to restructure and rethink their process, and in conditions: eight, they introduced five new editors who would be joining them. At the same time, another of the original editors, Jan Clausen, decided to leave the collective after nearly six years of editorial work (conditions: eight). The new editors had a lot in common, they were all lesbian writers and political activists born in the late 1940’s, but they did add a lot of diversity to the editorial collective; while the original four editors had all been white and middle class, the new had much more diverse backgrounds. Cherríe Moraga even acted as their office manager (conditions: eight). The new collective seemed to function well, putting together an excellent 195-page anthology for conditions: nine. However, the loss of NEA funding shook them to their roots soon after. Four editors left the collective, including Rima Shore, one of the founding editors, leaving Elly Bulkin as the only remaining founder. The remainder of the collective put off the publishing of conditions: ten until they could find women to replace those who had left and alternative funding sources (conditions: ten).

After these years of crisis forced it into a more flexible structure, conditions seemed to stabilize, publishing annually without delay until 1990. Though they did survive, it was only by the skin of their teeth. Conditions’ story demonstrates both the benefits and detriments of government funding for activist art. On one hand, it can allow important publications that would otherwise be financially unviable to exist. On the other hand, it is subject to political forces, putting important publications constantly in danger as they become pawns in a much larger political game. Within this flawed system, conditions was able to survive as a non-profit that could collect donations from a variety of sources. Even when federal funding went away, state funding, grants from various organizations, and individual contributions kept them afloat. Perhaps a less exceptional publication would not have been able to navigate the same crises, but conditions demonstrated over and over that its content was timely and relevant, at the cutting edge of feminism.

Sources:

conditions: one, Bulkin, Elly., Clausen, Jan., Klepfisz, Irena., Shore, Rima. 1977.

conditions: four, Bulkin, Elly., Clausen, Jan., Klepfisz, Irena., Shore, Rima. 1979.

conditions: six, Bulkin, Elly., Clausen, Jan., Klepfisz, Irena., Shore, Rima. 1980.

conditions: seven, Bulkin, Elly., Clausen, Jan., Shore, Rima. 1981.

conditions: eight, Bulkin, Elly., Clausen, Jan., Shore, Rima. 1982.

conditions: ten, Bulkin, Elly., Allison, Dorothy., Clarke, Cheryl., Otter, Nancy Clarke., Waddy, Adrienne. 1984.

Levy, Alan Howard. Government and the Arts: Debates over Federal Support of the Arts in America from George Washington to Jesse Helms. Lanham, MD, University Press of America,1997.

Uchmanowicz, Pauline. “A Brief History of CCLM/CLMP.” The Massachusetts Review 44.1 (2003): 70-87. ProQuest. Web. 20 Nov. 2019.

National Endowment for the Arts. 1987 Annual Report. Washington D.C., Office of Communications of the National Endowment for the Arts,1987. Web. 22 Nov. 2019.

Macarthur, Mary. “Grants Going Nonstop to Little Magazines.” New York Times, 5 April 1983, p. A26. Web. 20 Nov. 2019.

After their first note to their readers in 1978, conditions received a major boost from the unprecedented success of conditions: five, the black women’s issue. As one of the first major anthologies of black feminist literature, conditions: five represented a major step forward for feminist publishing. Readers were clearly hungry for this kind of content, as it sold four times as many copies as any previous issue, with print runs totalling 10,000 copies (conditions: six, p. [vi]). This issue also gave the regular editors a break, as it was guest-edited by Lorraine Bethel and Barbara Smith. However, one successful issue did not insure the future of the magazine, and 1980 hit conditions as hard as anyone else.

After their first note to their readers in 1978, conditions received a major boost from the unprecedented success of conditions: five, the black women’s issue. As one of the first major anthologies of black feminist literature, conditions: five represented a major step forward for feminist publishing. Readers were clearly hungry for this kind of content, as it sold four times as many copies as any previous issue, with print runs totalling 10,000 copies (conditions: six, p. [vi]). This issue also gave the regular editors a break, as it was guest-edited by Lorraine Bethel and Barbara Smith. However, one successful issue did not insure the future of the magazine, and 1980 hit conditions as hard as anyone else.