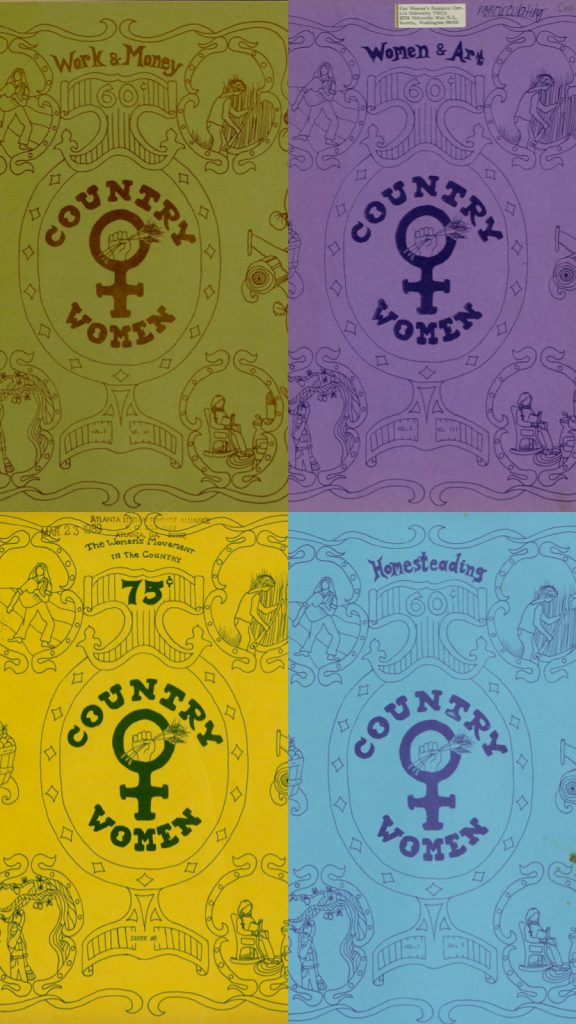

Four covers of the Country Women periodical, covering topics such as “Homesteading” and “Work & Money,” depicting a venus symbol with a fist inside of the circle, clutching a grain of wheat. Various line drawings skirt the outer edges of the covers showing women spreading seed, picking fruit, and reading.

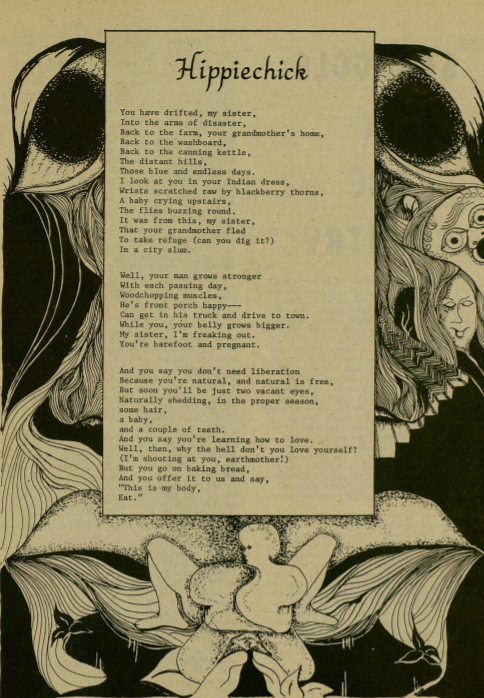

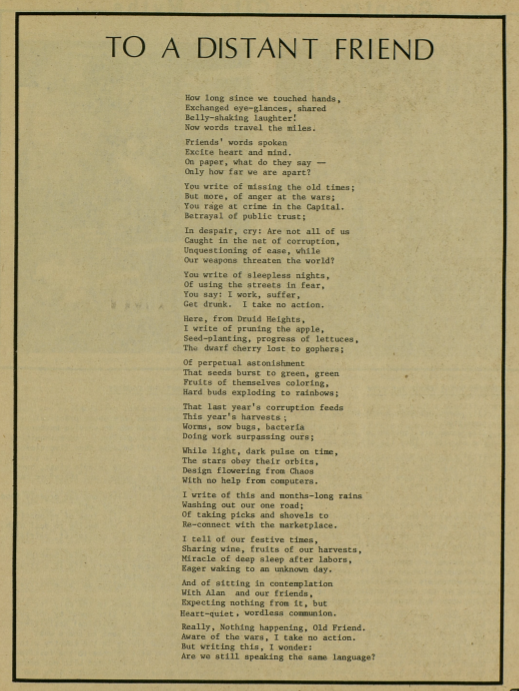

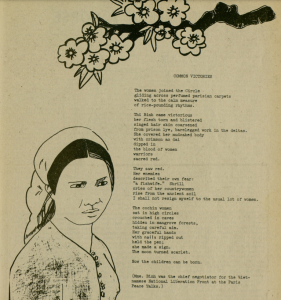

Though most periodicals of the second-wave feminist movement emerged out of major U.S. cities, rural feminist literature managed to become part of the national feminist consciousness. One of the most prominent of rural feminist periodicals is Country Women, a journal published out of Mendocino County in California from a women’s farming commune. The journal describes itself as “a feminist country survival manual and a creative journal” (Country Women). This highlights the two-pronged approach of the rural feminist project: creating a rural lifestyle that is more empowering for women and making space for the artistic endeavors of rural women. Art was critical to the Second Wave feminist movement, and this remains true amid rural feminist circles. Many scholars of the second-wave feminist movement note “the centrality of poetry in the feminist projects of the 1960s and 1970s” (Voyce 162). This is certainly seen in Country Women which features prominently the poetry of rural women. The poems are often set alongside or within line art that provides both context for the poetry and a reminder of the necessity of artistic expression by women within the feminist movement. In a piece entitled “We’re Not Just Farmers,” one country woman laments the leading role that practical farm chores plays in her life and warns against denying the part of oneself that longs for beauty, arguing that “we need to take the artistic parts of ourselves more seriously” (Rodgers 6). Not only does Country Women show that rural women are not lacking in feminist ideology, it also shows that the feminist poetry movement is alive and well in the countryside. Rural women are not simply tending to the farmhouse all day; they are writing poetry, blowing glass, painting landscapes, and drafting political essays. Even as Country Women encourages rural women to make artists of themselves, the journal does not deny the importance of practical skills that pertain to a country lifestyle, specifically when it comes to work that is seen as traditionally male labor. Country Women advertised itself in a fellow feminist publication, Heresies, as devoting half of its content to writings and art focused around a theme relevant to the women’s movement and centering the other half on “learning specific skills [such as] building a solar energy collector, caring for cows and goats, reglazing windows, and winter gardening” (Heresies 122). The reality of country life can be brutal; it is not all just feasting on one’s harvests and relaxing in meadows. Women must have the practical skills to run a successful farm and make a living, especially considering that most young girls growing up in the country are not necessarily instructed upon how to operate a farm and the equipment that comes along with it. This information is usually bestowed upon sons. Women existing in traditionally masculine spaces such as the farm or the literary world itself is a radical act, and Country Women provides critical documentation of these routine radical acts throughout the Second Wave feminist movement.

Works Cited:

Country Women. Vol. 1, no. 3, Country Women Editorial Collective, 1973.

Heresies. Vol. 2, no. 2, Heresies Collective, 01 Jul. 1978, p. 122.

Rodgers, Amy. “We’re Not Just Farmers.” Country Women, no. 22, Country Women Editorial Collective, 01 Dec. 1976, p. 6.

Voyce, Stephen. “The Women’s Liberation Movement: A Poetic for the Common World.” Poetic Community, University of Toronto Press, 04 May 2013, pp. 162- 201.