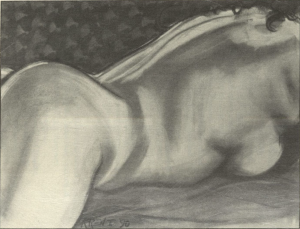

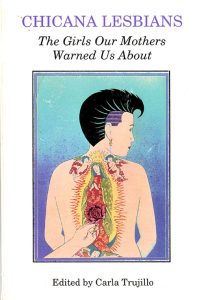

The original cover of Carlo Trujillo’s anthology “ Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About features La Ofrenda, from the National Chicano Screenprint Taller by Ester Hernandez, 1990.

The cover of Trujillo’s anthology Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About is adorned by Ester Hernandez’ La Ofrenda. It depicts a subtle show of intimacy between two women, a romantic rose offered to a tattoo of the Virgin de Guadalupe on a woman’s back. It unites both queer imagery with Chicana cultural icons to illustrate the overlap between communities. The Virgin de Guadalupe, known in English as the Virgin Mary, holds immense significance to the Chicana/o/x community to the extent where it has become a national symbol of Mexico. She is hailed as the religious deity whose apparition reconciled the Spanish and Indigenous people in the 19th century for the creation of one Mexico under Catholicism. She has also been used as a political symbol in the Mexican revolt against the Spanish by Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (Virgen de Guadalupe 1). Her image possesses a great magnitude within Mexican culture as a virtuous holy woman. Her portrait as a tattoo on the back of a woman who presents as a butch dyke is a tangible clash of Chicano and lesbian culture. The height of Mexican female expectation represented through the Virgin Mary juxtaposed with lesbianism speaks strongly to women with a foot in both worlds. Chicano culture tarnished by homophobia is unable to hold space for the existence of these women, and the conceptions of lesbianism as white only also do not allow for their presence. The presentation of this dichotomy as a place of intimacy is revolutionary for our conceptions of Chicana lesbians. The presence of Virgen de Guadalupe honors Chicana culture while holding space for criticisms of its homophobia. It also shows the existence of Chicana women within lesbian culture, and demonstrates that their cultural identities do not have to be sacrificed to actualize their queerness. The simple act of a rose extended as an offering of love humanizes the sometimes polarizing cultural divide between lesbianism and Chicano culture.

Trujillo, Carla, and Ester Hernandez. “Cover, La Ofrenda.” Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About, Third Woman Press, Berkeley, 1994.

“Virgen De Guadalupe.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/patron-saint.