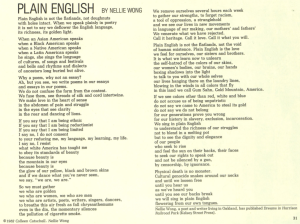

Although Asian American activists were key figures during the Second Wave, their political work was rendered invisible for a large part of the movement, as evidenced by their lack of presence in mainstream feminist periodicals. While Asian Americans were fairly active, their namelessness is a byproduct of most Asian cultures that encourage submissiveness and gentility in the face of authority. Women were discouraged from expressing their emotions, which were seen as shameful and weak, in Confucian society. Confucian patriarchs preached a “master-servant” relationship to enforce a rigid class structure and unwavering obedience to the family (Lee 66). As such, women were subjugated under their husbands and fathers, who held “absolute power” over every interaction.

“Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk.” a painting by Zhang Xuan depicts Confucian women performing traditionally domestic and subservient tasks

In the Korean Yi dynasty, women expelled their emotions through anonymous confessional literature, a silent mode of communicating frustrations that internalized deference and complacency within Asian women (Lee 66). Typically Eastern values of silent femininity and submissiveness serve as a stark contrast to Western values that champion assertiveness and progression.

Political influences such as racist U.S. policies and the WWII internment deprived and exploited Asian Americans in their pursuit of citizenship and assimilation into Western culture. The low population of Asian American women is a direct and intentional result of immigration policies that stripped Chinese immigrants of their rights. Policy writers during the 1850s aimed to capitalize on the cheap labor of Chinese immigrants and discouraged laborers from finding a spouse in order to keep their labor force alive. Hence, US immigration policies established restrictive, discriminatory, and sexist quotas for Asian women and children. Additionally, Chinese prostitution during the 19th century became a scapegoat for sinophobic sentiments that hindered the growth of the Asian American population: “… at least eight California codes were passed, all aimed at restricting the importation of Chinese women for prostitution and the suppression of Chinese brothels. Although white prostitution was equally, if not more, prevalent, these were additional and specific laws directed only against the Chinese” (Hirata 27). In the Page Act of 1875, the California commissioner of immigration outlined that “lewd” or “debauched” women were strictly prohibited from immigrating into California (Hirata 10). Officers took advantage of the vague language and prohibited the immigration of most Asian women into the country. Furthermore, the characterization of Chinese women as inherently sexual fueled the notion that Asian women were immoral and further subjected them to fetishization.

Institutional discrimination persisted in the form of anti-miscegenation laws that discouraged laborers from forming families: “the passage of anti-miscegenation laws, rules unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1967 barred marriage between whites and “Mongolians” and laborers of Asian origins, making it impossible for Asians to find mates in this country” (Chow 291). More laws were directly targeted at Chinese women to keep them from marrying American citizens, yet allowed their children to enter the states as laborers.

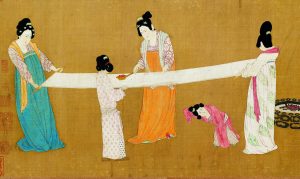

A memorial plaque located in Manzanar, CA honors the victims of the Japanese internment camps, published in the 2nd volume of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics

In the early 1940s, the establishment of the Japanese internment camps fueled Anti-Asian rhetoric that hindered the political progress of Asian American success. The internment camps, which were designed to capitalize off of Japanese-American labor to “turn worthless land into post-war public assets,” cost less to the government than prison labor. After the abolishment of internment camps, Japanese Americans who chose to stay on the West Coast rather than relocating to the Midwest “faced the danger of violence, terrorists, unexplained fires, beatings, threats” (Ikeda-Speigel 94). Legal obstacles and public pressure made it increasingly difficult for Japanese Americans to assimilate back into American society as they were prohibited from obtaining a business license, owning a house, acquiring a job, and burial in their hometown cemeteries” (Ikeda-Spiegel 94).

The slow growth of the Asian American population due to immigration laws and dehumanizing practices served as obstacles to class and social development for the wider community. Early activist groups spearheaded by wealthy and educated Asian American women were “few in number and with little institutional leadership” (Chow 287). As a result, these groups lacked institutional support, were normally conservative, and primarily targeted issues regarding ethnicity over gender.

Sources:

Chow, Esther Ngan-Ling. “The Feminist Movement: Where Are All the Asian American Women?” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. University of Hawai’i Press, Sept. 1992, pp. 96–111.

Hirata, Lucie Cheng. “Free, Indentured, Enslaved: Chinese Prostitutes in Nineteenth-Century America.” Signs, vol. 5, no. 1, University of Chicago Press, 1979, pp. 3–29.

Ikeda-Speigel, Motoko. “Concentration Camps in the U.S.A.” Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts and Politics. vol. 2, issue 4, Heresies Collective, 01 Sept. 1979, pp. 90-97.