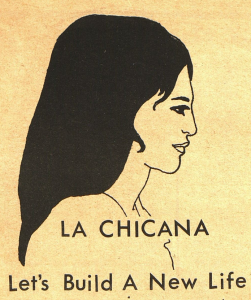

Artwork by Enriqueta Longauex y Vasquez featured in It Ain’t Me Babe, 1975.

The rise of political consciousness is present in “La Nueva Chicana” by Ana Montez. Published in the periodical, The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union in 1975, it calls for unity within la raza, meaning the people. The poem begins by describing the young Chicana as a bareheaded girl, rejecting traditional markers of femininity in favor of a shaved head, emblematic of her transition from a meek constructed femininity to La Nueva Mujer, meaning The New Woman. This is a reference to the idea of a new feminist ideal that was popularized in the late 19th century amidst first wave feminism, and who was known for actively resisting traditional norms and forging her own path towards equality (Stevens 27). The use of The New Woman also rebukes machismo, which is the presence of an exaggerated and restrictive masculinity present in Chicano culture. La Nueva Chicana is becoming The New Woman in two senses: by identifying with a historical feminist culture that had not always been accessible to their community, and by rejecting critiques by Chicano men that feminism violates the traditional expectations of Chicana women. Montes makes a concerted effort to connect with the canon of the first wave feminist movement, as well as the illustrate the unique oppressive struggles Chicana women faced within their community. Doing so grounds La Nueva Chicana’s passion as legitimate yet eager to embark on forging partnerships in the name of equality. The poem goes on to define the strategy of La Nueva Chicana, which is one of unity and collaboration. Montes illustrates, “You do yours and I’ll do mine/ is not her bag/ it’s let’s do it together /JUNTOS VENCEREMOS” (5-8). Juntos Vencermos means succeeding together, and demonstrates the goals of the Chicana feminist faction to resist fragmentation in the name of distinct coalitions. Montes then highlights the unique strengths of the new Chicana, and how her duality positions her to be a catalyst for social change in both the feminist and Chicano movements. Her softness is the compassion and empathy that fuels her desire to help, which is juxtaposed with the depiction of her as the “mightiest weapon”. Her strength and the capacity to make an impact is integral to the essence of the new Chicana. Her courage to be a frontline contributor to the goals of the movement can be seen in the, “ emerged from the shadows/ she’s out in font.”. Montes’ reference to the Chicana women as emerging from the shadows speaks to their long-waited ascent into a political consciousness that could be funneled into activism and liberation from machismo. Th poem concludes by lauding her newfound empowerment and recognizing its potency for change,

“VIVA LA RAZA

Is her battle cry

She is no longer the silent one

She has cast off the shawl of the past

To show her face

She is LA NUEVA CHICANA”

(Montes 21-25). The last stanza evokes a poignant image of the coming together of La Nueva Chicana, who has cast off the stereotypes that adorn her as passive and weak. This is a rejection of the patriarchal Chicano culture and American culture. The shawl, a traditional item of clothing for Mexican women represents the chains her culture bestows upon her as a result of her gender. It establishes the reveal of the Chicana’s true face as the future of the Chicano movement, and how her social action will define the next era of Latinx women. The poem is not disparaging or angry, but rather a clear acknowledgement of the struggles the Chicana has faced to gain this level of liberation. It is a commendation of their ability to preserve and then choose to dedicate their energy to both the Chicano and feminist movements.

Longauex y Vasquez, Enriqueta. “La Chicana, It Ain’t Me Babe.” 15 Jan. 1975.

Montes, Ana. “La Nueva Chicana, Chicago Women’s Liberation Union.” 1 Aug. 1975.

Stevens, Hugh (2008). Henry James and Sexuality.Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780521089852.