In 1970, Francisca Flores founded the Los Angeles magazine Regeneración, which Chicana feminist scholar Maylei Blackwell describes as a source of “vital contributions through…singularly forthright analysis regarding women’s issues” (61). In that vein, the editors of Regeneración devoted two full issues (1971, 1973) to solely considering the Chicana women’s struggles (Blackwell 62). While a number of other publications, including Chicanas en la Literatura y el Arte, were printed from within traditional outlets first popularized by figures from the Chicano movement, Regeneración was an example of a publication that formed organically, as Chicana women sought to better understand their relationship with feminism, cultural forces, and each other. In the editorial statement of Regeneración’s special Chicana issue from 1971, Flores emphasizes, “The issue of equality, freedom, and self-determination of the Chicana — like the right of self-determination, equality, and liberation of the Mexican community — is not negotiable. Anyone opposing the right of women to organize into their own form of organization has no place in the leadership of the movement” (1). In no uncertain terms, Flores calls attention to the hypocrisy of those belonging to the Chicano movement who would actively oppose the project of extending the emerging rights of the Chicano man to the Chicana woman through feminist organization. Further, in the article “Conference of Mexican Women: Un Remolino” in that same issue, Flores responds to criticisms that Chicana women who reject the so-called traditional roles of mother or home-maker are in “betrayal of [Chicano] culture and heritage” (1). Her fierce and famous rebuttal, “Our culture hell,” demonstrates her commitment to her fellow Chicana woman above all, as it is the exploitation of the Chicana woman which must be recognized before any true progress can be achieved (Flores 1). It is with this guiding principle that Regeneración takes form.

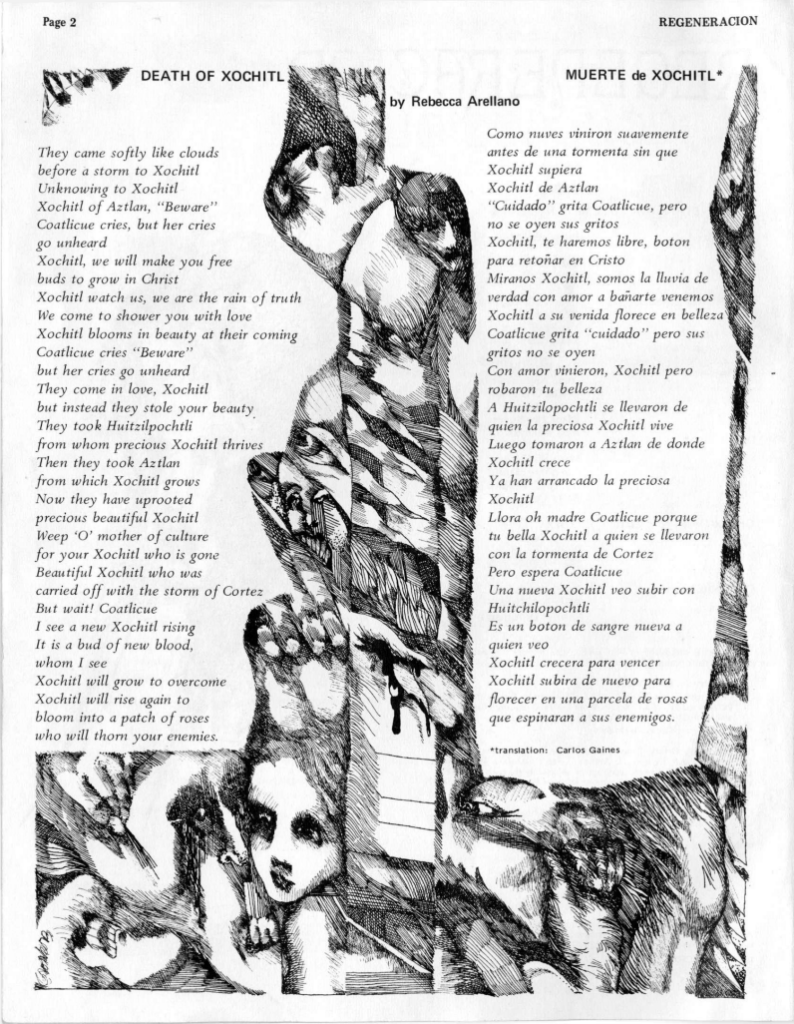

A display of Rebecca Arellano’s “Death of Xochitl” poem, which bemoans colonizing forces and envisions a return of Chicana feminism in its most divine form, accompanied by a drawing of an intruding wall of faces and faceless entities.

Published in 1973, the second special Chicana issue of Regeneración embodies the pragmatic yet authoritative feminism practiced by the women on the front lines of the burgeoning movement, as they made strides toward claiming the natural rights of the Chicana woman. In particular, the approach taken by Flores and her co-editors was to caution that the additional strenuating conditions placed on the Chicana woman render her struggles not equal to that of the white woman and thus important to consider on their own to avoid forming an imbalance alliance. In recognition of this concern, the issue opens with Rebecca Arellano’s “Death of Xochitl,” a poem reflecting on the erasure of Chicano/a histories at the hands of white colonizers, printed fully in both English and Spanish (2). Its subject, Xóchitl, the flower goddess of Aztlan, which is the Aztec homeland, was “uprooted” from her people and “carried off with the storm of [Hernán] Cortés” (Arellano 2). In choosing to focus on the feminine form Xóchitl, Arellano points to the ways in which this repeated cycle of forced removal and assimilation has harmed indigenous and Chicana women, their rich mythology and their trust corrupted in principle by violence and violation. However, she concludes her poem with a nod to the Chicana’s growing sense of unrest with the status quo and the heightened fervor of Chicana political organization, made possible by the distribution of feminist ideas through presses, conferences, rallies, and universities. In the emergence of the Chicana feminist movement, Arellano sees a force greater than any human scale:

I see a new Xóchitl rising

It is a bud of new blood, whom I see

Xóchitl will grow to overcome

Xóchitl will rise again to

bloom into a patch of roses

who will thorn your enemies. (Arellano 2)

Arellano’s message of liberation via personal and collective insurgency carries the weight of the movement and is echoed in a line from Diane Drollinger’s poem “Soy Nada Más Que Una Chicana,” which reads as an exclamation of self-love:

QUE VIVA MI RAZA

MI RAZA QUERIDA

QUE VIVA LA CAUSA

LA CAUSA DE VIDA! (Drollinger 25)

Drollinger’s exclamation represents the fact that Chicana women are claiming both their race and their right to broaden the aims of La Causa, the Chicano movement.

Over the course of its publication, which extended until 1975, Regeneración transitioned from a news source to a collection of editorials, poetry, and art which articulated new and exciting expressions of Chicana feminism. The magazine evolved as both a feminist press and a nexus of Chicana self-interpretation and self-determination, linking readers to budding Chicana feminist voices, advertising Chicana journals that sprung up across the United States, and promoting grassroots organization, including Flores’ Chicana Service Center and her Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional political group. While Regeneración was not the only Chicana feminist periodical to lay out new ideas for the radical inclusion of Chicana women, its ability to retain a distinctly feminist identity against pressures to merge with collectives with different priorities or to dissolve completely was its characteristic achievement. Regeneración and the network of Chicana-run presses that emerged separately from white feminist presses during the early 1970s set a precedent of Chicana women publishing Chicana feminist texts and laid the groundwork for new Chicana voices to articulate their feminisms throughout the decades to follow.

Works Cited:

Arellano, Rebecca. “Death of Xochitl.” Regeneración, vol. 2, no. 3, 1973, p. 2.

Blackwell, Maylei. “Contested Histories: Las Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, Chicana Feminisms, and Print Culture in the Chicano Movement, 1968–1973.” Chicana Power! : Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement. 1st ed. Austin: U of Texas, 2011. Chicana Matters Ser. pp. 59-84.

Drollinger, Diane. “Soy Nada Más Que Una Chicana.” Regeneración, vol. 2, no. 3, 1973, p. 25.

Flores, Francisca. “Conference of Mexican Women: Un Remolino.” Regeneración, vol. 1, no, 10, 1971, pp. 1-3.

Flores, Francisca. “El Mundo Femenil Mexicana Regeneración.” Regeneración, vol. 1, no. 10, 1971, p. 1.