Starting in 1967, Quinto Sol, an independent publishing house at the heart of the Chicano movement, released prints of El Grito: A Journal of Contemporary Mexican-American Thought. The journal served as foundational text for educational initiatives geared toward expanding Chicano Studies programs and curriculums, yet its research noticeably lacked Chicana voices, as Chicana researcher Roberta Fernández highlights in her work “Abriendo Caminos in the Brotherland: Chicana Writers Respond to the Ideology of Literary Nationalism.” In fact, only one Chicana woman served on its editorial board, and a mere four Chicanas were published in the entirety of the journal (Fernández 31). Thus, despite the monumental advances of new forms of student activism and newspaper participation, there still remained corners of the Chicano press world which were largely resistant to the upward trajectory of Chicana authors and editors.

It was not until El Grito released its final journal copy in 1973 that Chicana authors were featured to an appreciable extent. At this time, the periodical transitioned from a journal to a book series and first printed Chicanas en la Literatura y el Arte, featuring the work of notable Chicana figures, including Estela Portillo, Ramona González, Angélica Inda, Lorenza Calvillo Schmidt, Dorothy Rangel, Adaljiza Sosa-Riddell, and Isabel Flores, with art by Lydia Rede Madrid (Chicanas en la Literatura y el Arte). The collection grounds itself in the lived experiences of its Chicana authors. Feminism, as a clearly defined concept, takes a backseat to such ideas as the remembrance of cultural roots, heritage, and the role of the individual woman in Chicana/o society. An instructive example of this difference can be found in Adaljiza Sosa Riddell’s “Como Duele.” Sosa Riddell references the details of her chosen assimilation into the United States, including the changing of her name and her ability to move around unperceived given her paler complexion (77). She mourns the fact that her former lover, by taking a different direction, ends up being sentenced to time in jail, and she questions what this means for her own cultural identity or potentially her lack thereof (Sosa Riddell 77). This positioning of Sosa Riddell’s speaker’s experiences somewhere between Mexico and the United States creates a narrative that is recognized by its Chicana/o readers aware of the pain of such experiences. However, the tone of the piece is more introspective than revolutionary, serving as a quiet reminder of the need for solidarity in the Chicano movement and, by extension, the Chicana movement. The speaker observes “what keeps me from shattering / into a million fragments? It’s that sometimes, you are muy gringo, too,” or, in other words, that she is not alone in her struggle with a fragile identity (Sosa Riddell 77).

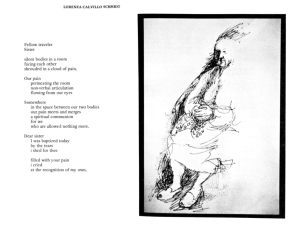

Lorenza Calvillo Schmidt’s “Fellow Traveler” poem (1973), as it appeared in the first publication of the El Grito book series. The knowing expression in the eyes of the older Chicana woman drawn here suggest that the Chicana/o struggles even transcend generations, alluding to a sense of solidarity.

This gesture of solidarity is repeated in Lorenza Calvillo Schmidt’s poem “Fellow Traveler,” in which two women address each other as sisters, or fellow travelers along a road marked by unavoidable pain and sorrow. As the road serves as a metaphor for the stretch of hardships endured in the lifetime of a Chicana woman, the fellow traveler is once again a sharer in the solace, another woman who understands the suffering. Calvillo Schmidt describes the intersection of the travelers’ pain as a “spiritual communion,” and as a consequence of that union, the speaker remarks, “filled with your pain / i cried / at the recognition of my own” (64). This realization is closely tied to the sort of consciousness raising exercises that were seen in the later edition of El Grito del Norte. However, the distinction between the two messages lies in the author’s tone, as Calvillo Schmidt’s use of the lowercase ‘i’ comes across as a realization of a power she lacks rather than the power she is determined to grasp. Ultimately, it is a sense of solidarity in past experience, rather than a forward-looking vision of feminism which defines Chicanas en la Literature y el Arte, and while the collection stops short of inspiring action, its calls for unity among Chicanos and Chicanas are nonetheless compelling.

Works Cited:

Calvillo Schmidt, Lorenza. “Fellow Traveler.” Chicanas en la Literatura y el Arte. El Grito, vol. 7, no. 1, 1973, p. 64.

Chicanas en la Literatura y el Arte. El Grito, vol. 7, no. 1, 1973, 83 pp.

Fernández, Roberta. “Abriendo Caminos in the Brotherland: Chicana Writers Respond to the Ideology of Literary Nationalism.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, 1994, pp. 23-50.

Sosa Riddell, Adaljiza. “Como Duele.” Chicanas en la Literatura y el Arte. El Grito, vol. 7, no. 1, 1973, p. 77.