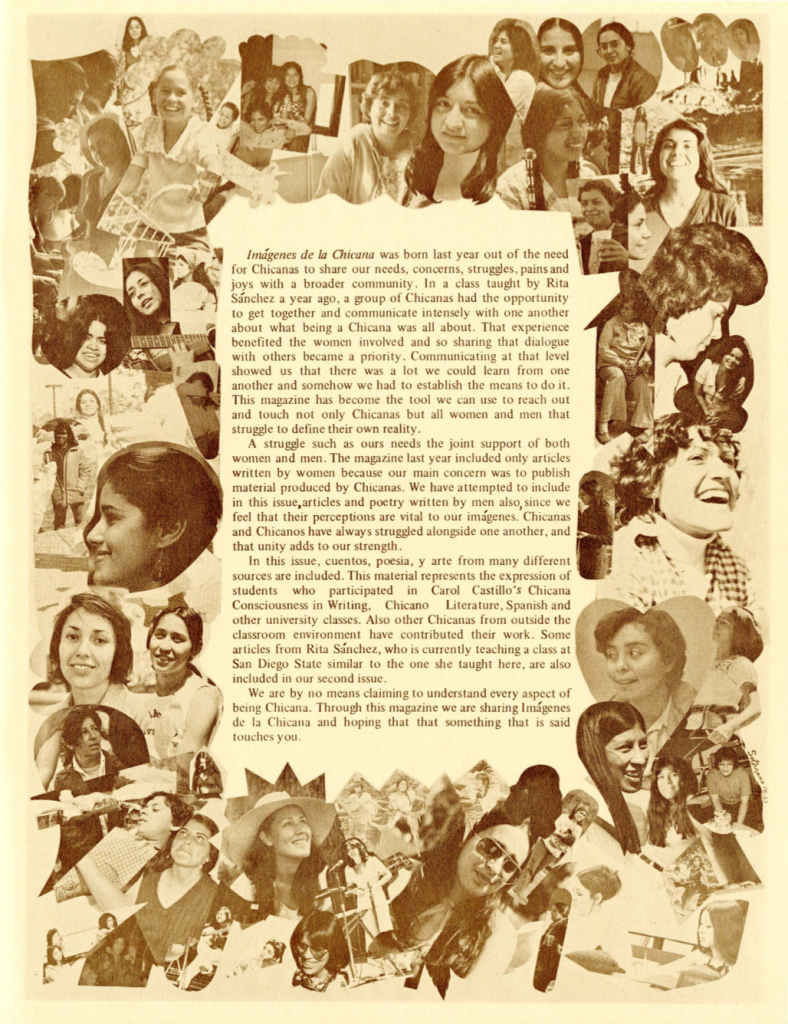

Founded in 1968 by Elizabeth “Betita” Martínez and Beverly Axelrod, the bilingual Chicana/o newspaper El Grito del Norte sought “to advance the cause of justice for poor people and preserve the rich cultural heritage of la Raza in [northern New Mexico]” by using familiar language to connect the struggles of its readership to the colonizing institutions culpable for their mistreatment (El Grito del Norte). In addition to calling attention to community needs and promoting Chicano interests in local politics, the newspaper acted as a safe space for women staff members to gain experience with the day-to-day operations of a full-scale news production. As a result, Chicana feminist contributors began to introduce ideas of the Chicana struggle for autonomy to the same audiences that were witnessing and broadly supporting the ongoing Chicano movement.

While it was originally intended to be published as a single article, Enriqueta Longeaux y Vasquez’s “¡Despierten Hermanos!” column became a focal point of El Grito del Norte and a key component of the newspaper’s emerging feminist disposition. In fact, Vasquez’s grito, her “scream,” consists of an urgent message to her Chicano brothers, who know what it is like to demand equal rights, to “wake up” and just as vigorously fight to defend the rights of their Chicana sisters. For example, in “The Women of La Raza, Part I,” Vasquez voices her frustration at the exclusion of Chicana women from the benefits of the Chicano movement. She describes the Chicana woman as one who “has had to suffer the torments of her people in that she has had to go out into a racist society and be a provider as well as a mother” and is “shunned again by her own Raza” when she attempts to become active in the Causa (10). The double oppression which Vasquez refers to here captures the dilemma faced by Chicana women advocating for greater agency at the time, namely the lack of belonging they felt to both the Chicano movement and the white feminist movement and thus a need to define themselves outside of both realms. Later, in “The Women of La Raza, Part II,” Vasquez shifts her focus to the Chicana women in her community, explaining “my dear sisters, we are bearing the brunt of raising our families in this barbarous society. We women must learn to function again like full humans, as did our ancestors,” alluding to the matriarchal prehistories woven into Mexican ancestral culture (13). By ending her stirring call to action with the words, “Let’s hold our heads high and proud and walk in beauty,” Vasquez suggests that engaging in political action as a Chicana woman is not only empowering but also consistent with ancient cultural tradition (13).

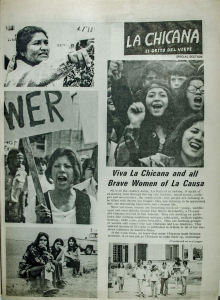

El Grito del Norte features images of Chicana girls and women in solidarity with one another in a variety of forms. The rallying cry of “Viva la Chicana” is made more poignant with the inclusion of individual people in photographs to relate the movement for equal rights back to.

A few years later, the excitement for feminist ideas building up from within El Grito del Norte gave rise to the publication of a newspaper section dedicated to “La Chicana.” Articles with evocative titles, such as “Viva La Chicana and All Brave Women of La Causa,” “Our Unknown Revolucionarias,” and “Chicanas in La Pinta” spanned the sixteen-page feature, complete with photos of women of all ages protesting for their rights. “Viva La Chicana,” introduces the feature with the emboldening proclamation that “Our people are refusing to be filled with shame any longer, they are refusing to be oppressed, they are demanding liberation and a decent life,” yet insists that this transformation cannot be completed without the “unused talents, brain, energy” of those women not yet active in the movement, perhaps because the “machos” in their lives have dismissed La Chicana’s role (A-B). In her article, “Message to My Sisters,” contributor Anita Rodriguez echoes the need for all Chicana women to consider the role of oppression in their lives: “[The Chicana] has a responsibility to chase out of her head all those gringo ideas and values that have sneaked in. She has a responsibility to say to all the men who keep her tied to the house and buying-buying-buying — you don’t fool me any more, ya basta!” (J). Vasquez, Rodriguez, and all the women in training on the editorial staff over the newspaper’s 1968-1973 run period witnessed first-hand the positive impact that their reporting and commentary inspired and shared that knowledge and experience as they moved on to other publications. The feminist themes present in El Grito del Norte and the methods of their circulation bear close resemblance to the consciousness raising groups of the parallel Second Wave Feminist Movement and can be viewed as a precursor to the use of other forms of media to accomplish similar goals of Chicana empowerment.

Works Cited:

El Grito del Norte, vol. 1, no. 1, El Grito del Norte Editorial Collective, August 24, 1968.

Longeaux y Vasquez, Enriqueta. “The Women of La Raza,” El Grito del Norte, vol. 2, no. 9, 1969, pp. 8-10.

Longeaux y Vasquez, Enriqueta. “The Women of La Raza II,” El Grito del Norte, vol. 2, no. 10, 1969, p. 13.

Rodriguez, Anita. “Message to My Sisters,” El Grito del Norte: La Chicana, vol. 4, no. 4-5, 1971, p. J.

“Viva La Chicana,” El Grito del Norte: La Chicana, vol. 4, no. 4-5, 1971, p. A-B.