“You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows…”

At the SDS National Convention in 1969, Karin Ashley, Bill Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn, John Jacobs, Jeff Jones, Gerry Long, Home Machtinger, Jim Mellen, Terry Robbins, Mark Rudd, and Steve Tappis submitted what would become the founding document of the Weather Underground: “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows….”

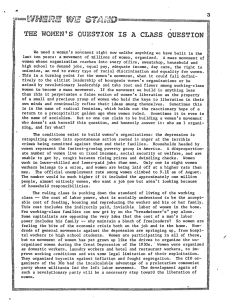

Image of “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows…” published in New Left Notes in 1969 by Karin Ashley, Bill Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn, John Jacobs, Jeff Jones, Gerry Long, Home Machtinger, Jim Mellen, Terry Robbins, Mark Rudd, and Steve Tappis.

Taking its title from Bob Dylan’s 1965 song “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” this document identifies that the primary task of the revolutionary struggle is to destroy U.S. imperialism and establish a communist world. The document identifies U.S. imperialism abroad and at home, specifically in the systemic oppression of Black people. They reject the notion that oppression against Black people only exists in the South and that Black people in the North are instead incorporated into white working-class society. Rather, they identify anti-Black racism as systemic and not confined to one geographical location. The group used the term “Black Colony” to express that in the U.S., “common features of oppression, history and culture… unify black people as a colony” (3). Recognizing that white people will never fully understand the lived experiences of Black people in America, the WUO positioned themselves as an armed white fighting force to back up the Black Liberation Movement. Proactively responding to the question of how the struggle for Black self-determination connects to the broader goals of the revolution and the establishment of communism, the group answered:

[A] revolutionary nationalist movement could not win without destroying the state power of the imperialists; and it is for this reason that the black liberation movement, as a revolutionary nationalist movement for self-determination, is automatically in and of itself an inseparable part of the whole revolutionary struggle against US imperialism and for international socialism (WUO 3).

The other key tenant of the founding document was the WUO’s stress on the importance of a youth-led revolutionary party. Identifying that most young people in the U.S. were a part of the working class, the WUO saw that “youth struggles are, by and large, working-class struggles” (13). In this way, involving and centering young people in the movement still responds to the issues faced by working-class adults but has the added advantage of ideological openness. Generally, the WUO wrote, young people “have less stake in a society (no family, fewer debts, etc), [and] are more open to new ideas (they have not been brainwashed…)” (14). It is easier, therefore, to organize and radicalize them, especially when young people had felt the impacts of U.S. imperialism their entire lives. The WUO identifies four examples of tangible ways U.S. imperialist ideology impact young people: first, jail-like schools where curriculums center American-exceptionalist myths, promote racist and anti-communist ideologies and make young people into capitalistic machines. Second, at the time, “youth unemployment [was] three times the national average” (15). Young people also work longer hours and are compensated less compared to their older counterparts. Third, the WUO reported that there were “two and a half million soldiers under the age of thirty who are forced to police the world [and] kill and be killed in wars of imperialist domination” (15). And finally, as these problems spread to more and more young people, police act in increasingly violent and oppressive ways. Ultimately, the WUO hoped that by centering young people who were working-class (members of the proletariat), the movement would be able to reach a wider audience and move away from a predominantly student elite base.

While most of the statement is centered on race and class, the WUO makes a point to discuss gender as well, specifically focusing on how the New Left has largely failed to address patriarchy and women’s issues. Because of these failings on the left, WUO acknowledged that “we have a very limited understanding of the tie-up between imperialism and the women question” (20). How then, the WUO asked, “do we organize women against racism and imperialism without submerging the principled revolutionary question of women’s liberation—we have no real answer” (20). Even though the group posits no answer to this question, their recognition of the fundamental ways women’s liberation is bound up in anti-imperialism is critical. The group offered the following regarding what they phrase as “the women question:”

To become more relevant to the growing women’s movement, SDS women should begin to see as a primary responsibility the self-conscious organizing of women. We will not be able to organize women unless we speak directly to their own oppression. This will become more and more critical as we work with more oppressed women. Women who are working and women who have families face male supremacy continuously in their day-to-day lives; that will have to be the starting point in their politicization. Women will never be able to undertake a full revolutionary role unless they break out of their woman’s role (WUO 6).

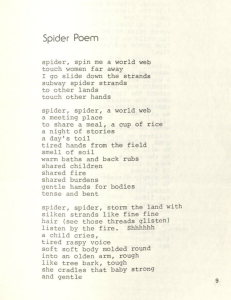

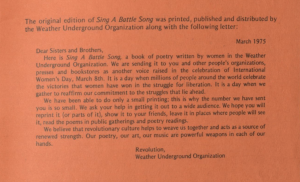

Osawatomie

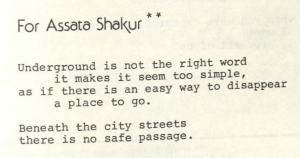

Later in the group’s history in 1975, they published a periodical titled Osawatomie, the nickname given to abolitionist guerilla warfare fighter John Brown during the Civil War.

Cover of volume 1, issue number 2 of Osawatomie which came out in the Summer of 1975.

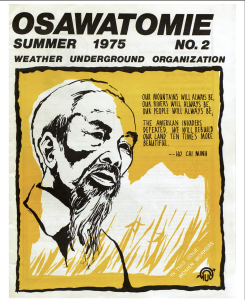

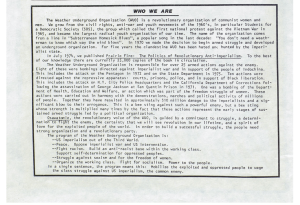

On the opening page of the periodical is the group’s “Who We Are” statement that outlines some of their campaigns and broader ideologies and goals. In this statement, we can see how women’s liberation has become an integral part of their political agenda. Explicitly listed as part of the group’s program is the “Struggle Against Sexism and for the freedom of women” (2). Additionally, the very first sentence of the statement reads that the WUO is a “revolutionary organization of communist women and men” (2). This explicit inclusion draws attention to how the struggle against imperialism is an intersectional struggle. Liberation from oppression based on class, race, and gender all envelop one another.

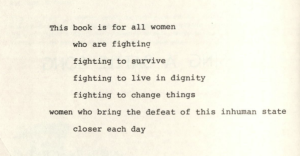

Image of the “Who We Are” statement that was published in the second issue of Osawatomie in the Summer of 1975.

Works Cited

Karin Ashley, Bill Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn, John Jacobs, Jeff Jones, Gerry Long, Howie Machtinger, Jim Mellen, Terry Robbins, Mark Rudd, and Steve Tappis. “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows.” New Left Notes, vol. 4, no. 22, SDS, June 1969, pp. 3-9.

Osawatomie, vol. 1, no. 2, Weather Underground Organization, Summer 1975.

Weather Underground Organization. “Who We Are.” Osawatomie, vol. 1, no. 2, Weather Underground Organization, Summer 1975, pp. 2.