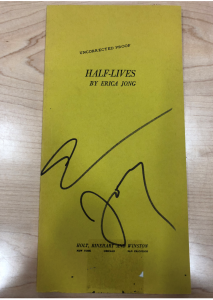

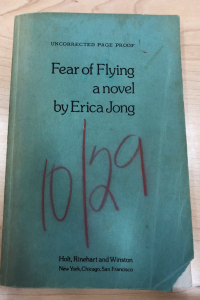

Before the 1973 publishing of Erica Jong’s novel Fear of Flying and her poetry book Half-Lives, editors and reviewers worked through Jong’s uncorrected proofs to ensure correctness and to pose literary criticisms before the works’ publication. Though the notes throughout each work vary, the meanings behind each marginal note remain poignant and interesting when compared to the published work.

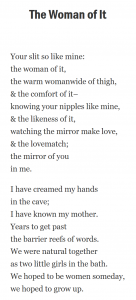

In the Half-Lives proof, there are no notes or edits. The only time a pen seems to have touched the paper is to add page numbers. This absence is interesting within itself, as it leaves Jong’s poetic ideas untouched. This reviewer did not take it upon themselves to criticize Jong’s poetry, or make their own remarks surrounding the work. This reader wanted to leave Jong’s work as it was, without the remarks or criticisms of an outside reader.

In the proof of Fear of Flying, however, is the exact opposite. All over the novel are black and red underlinings, as well as one-word notes including “ego-centric” and “over-written.” These small edits and criticisms shed light on the reviewer’s opinions of Jong’s work as well as their purpose in reading the work. The reviewer of the Fear of Flying proof was Terry Stokes, a writer for The New York Times who was charged with writing a review of Jong’s debut novel. Though he seems to think some things are writerly “excess,” the most resounding aspect of his marginal additions is the sheer number of underlines and stars next to passages he finds important for his article. His comments also beg certain questions from onlookers: are Stokes’ comments excessive and if so, why? Is he overly critical of Jong’s work because of its blunt addressing of female sexual fantasy, or does he believe that Jong was gratuitously over-descriptive?

Sources:

Jong, Erica. Fear of Flying. Holt, Reinhart, and Winston Publishers, 1973.

Jong, Erica. Half-Lives. Holt, Reinhart, and Winston Publishers, 1973.