Never Meant to Play Sports

Life before Title IX for women in sports was terrible. Why would it be anything else? Sports were never created with the intention of women playing them. Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics, said in the early 1900s, that “the Olympic Games must be reserved for men.” It must be, in his words, “the solemn and periodic exaltation of male athleticism” (McDonagh and Pappano, 39):

The final line of this assertion speaks directly to what sports meant for women: watching, following, and cheering on men whenever they played. “Female applause” was their “reward”.

This belief, that women should not play, or rather should not play on a major stage, stems from the idea that women and men are on opposite ends of the physical spectrum. It stems from the idea that women would never be able to play at the same level of physicality, intensity, and athletics as men (Mangan and Park, 289). The understanding that males and females are physically different triggered stereotypes of male and female physical attributes, in addition to developing the notion that males and females were on the opposite end of the physical spectrum.

Men further attempted to displace women from excelling in sports out of fear: as Lorber argues, “Men feared that they might be challenged or even displaced in governance of the basic social order…. Overall, they feared that they would lose control of public, political, social, and economic affairs” (Mangan and Park, 282). Men sought to assert their societal dominance over women through sports. They boasted about their involvement in sport as a proof of masculinity, especially if their gender identity seemed threatened. For instance, as explained in From Fair Sex to Feminism by J.A. Mangan and Roberta Park, composer Charles Ives feared that his musical interests made him seem effeminate. When he was asked what he played in his youth (an open-ended question), he simply replied “shortstop” with no mention of his musical interests (Mangan and Park, 283). This fear of losing identity and purpose drove men to continually promote their athletic dominance, making it harder for women to enter this space.

Prior to 1972, Mangan and Park argue, not only were women discouraged from playing sports by men, but they were also criticized (in regard to their athletic ability). In fact, male performance was often the standard against which female performance was measured (Mangan and Park, 285). If women performed well in male-heavy sports, their femininity was questioned. Women should not perform well in football or basketball was the thought. And so, men made sure women did not expand outside of a small subset of sports like tennis or gymnastics (Mangan and Park, 286).

Men always dreamed of dominating the sports space, dating all the way back to 1892 when the Chicago Graphic declared: “Football is typical of all that is heroic in American Sport… the capacity to take hard knocks which belongs to a successful football player is usually associated with the qualities that would enable a man to lead a charge up San Juan Hill” (Mangan and Park, 290). Being dominant in sports, for men, was associated with being a leader, having perseverance, courage, and determination. These ideals for men in sports have continued into modern day conversations, as sports are believed to teach young men valuable lessons like leadership and hard work. The quotations to left are from women from 1900-1956, expressing their thoughts on their inability to participate in sports. Evidently, females wanted to play sports, they just weren’t able to (Mangan and Park, 290).

Men always dreamed of dominating the sports space, dating all the way back to 1892 when the Chicago Graphic declared: “Football is typical of all that is heroic in American Sport… the capacity to take hard knocks which belongs to a successful football player is usually associated with the qualities that would enable a man to lead a charge up San Juan Hill” (Mangan and Park, 290). Being dominant in sports, for men, was associated with being a leader, having perseverance, courage, and determination. These ideals for men in sports have continued into modern day conversations, as sports are believed to teach young men valuable lessons like leadership and hard work. The quotations to left are from women from 1900-1956, expressing their thoughts on their inability to participate in sports. Evidently, females wanted to play sports, they just weren’t able to (Mangan and Park, 290).

Essentially, men believed they were physically better and naturally born to play sports, while women were naturally born to applaud them and clean the dishes (McDonagh and Pappano, 30).

Although men are physically bigger, have more upper-body strength and muscle mass than women, this does not mean they are athletically superior to women. Some physical attributes associated with women as a group – such as lower center of gravity, lower weight, and a greater percentage of body fat – are athletically advantageous. For example, in swimming, a woman’s higher body fat provides more buoyancy and protection from frigid waters. Also, lower weight allows for women to have an edge in super endurance running.

Prior to Title IX, Senator George McGovern exclaimed “prejudice against women [was] the last socially accepted bigotry” in 1971, representing the discrimination women constantly felt during these years (McDonagh and Pappano, 77). As the Second Wave Feminist Movement began to develop in the late 1960s, women soon began to fight for equal rights in sports as well. They were tired of being an afterthought, and Title IX (passed in 1972) was the first step in changing the way women were seen in sports.

Sources:

Mangan, J. A., and Roberta J. Park. From ‘Fair Sex’ to Feminism: Sport and the Socialization of Women in the Industrial and Post-Industrial Eras. Cass, 1987.

McDonagh, Eileen, and Laura Pappano. Playing with the Boys: Why Separate Is Not Equal in Sports. Oxford University Press, 2009.

In 1972, Title IX was established to provide everyone with equal access to any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance, including sports. This means that public schools and universities, which are federally funded institutions, are legally required to provide equitable sport opportunities to girls and boys. This is why these institutions now have the same number of women’s sports as there are men’s sports.

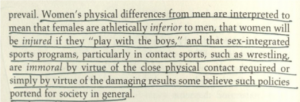

In 1972, Title IX was established to provide everyone with equal access to any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance, including sports. This means that public schools and universities, which are federally funded institutions, are legally required to provide equitable sport opportunities to girls and boys. This is why these institutions now have the same number of women’s sports as there are men’s sports. It is important to note that in terms of the quality of participation of these women, it is not enough for there to be equal opportunity to participate in a sports program if “participate” means just going through the motions. Women should have equal opportunity to receive the benefits of the program through interested participation. Title IX opened the door for women who want these benefits to receive them (McDonagh and Papano, 24). The passage to the left from Sports Illustrated notes the serious discrimination women faced in 1973 if they wanted to participate in competitive sports (Postow, 287).

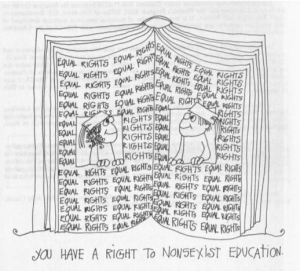

It is important to note that in terms of the quality of participation of these women, it is not enough for there to be equal opportunity to participate in a sports program if “participate” means just going through the motions. Women should have equal opportunity to receive the benefits of the program through interested participation. Title IX opened the door for women who want these benefits to receive them (McDonagh and Papano, 24). The passage to the left from Sports Illustrated notes the serious discrimination women faced in 1973 if they wanted to participate in competitive sports (Postow, 287). During the 1970s, The Guide to Title IX handbook (the cover is seen to the left) served as a “public service announcement” to readers to remind them that everyone, particularly women, “have a right to nonsexist education” (Sadker, Myra, and Elsa, 4). Created in 1974, the guide goes through all the aspects of Title IX and informs women on their rights under the new law. Hoping to reduce discrimination against women and to enforce the law in a more direct manner, the handbook goes through what it means to have a nonsexist education, what it means to not have discrimination in sports, and encourages young women to stick up for their new rights. A revolutionary law that changed the educational and sporting lives of young women, this guide helped to increase awareness of the law and promote young women to join sports.

During the 1970s, The Guide to Title IX handbook (the cover is seen to the left) served as a “public service announcement” to readers to remind them that everyone, particularly women, “have a right to nonsexist education” (Sadker, Myra, and Elsa, 4). Created in 1974, the guide goes through all the aspects of Title IX and informs women on their rights under the new law. Hoping to reduce discrimination against women and to enforce the law in a more direct manner, the handbook goes through what it means to have a nonsexist education, what it means to not have discrimination in sports, and encourages young women to stick up for their new rights. A revolutionary law that changed the educational and sporting lives of young women, this guide helped to increase awareness of the law and promote young women to join sports. Women who excelled at sports were perceived as freakish.

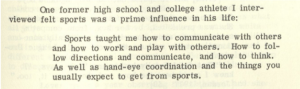

Women who excelled at sports were perceived as freakish. Male athletes were often treated as freakish, anomalous, and eccentric as well (Mrozek, 287). However, their acceptance of these stigmas accelerated at a much faster rate than that of women (as exemplified in the quote to the right). These male athletes were glorified for their success, while a woman was considered a “tomboy” or a “lesbian.” As Janice Kaplan writes in Women and Sports, it seemed clear that girls had babies to show they were women while men had footballs to prove they were men.

Male athletes were often treated as freakish, anomalous, and eccentric as well (Mrozek, 287). However, their acceptance of these stigmas accelerated at a much faster rate than that of women (as exemplified in the quote to the right). These male athletes were glorified for their success, while a woman was considered a “tomboy” or a “lesbian.” As Janice Kaplan writes in Women and Sports, it seemed clear that girls had babies to show they were women while men had footballs to prove they were men. With this newfound respect and realization of the powerful impact of sports, women began to get involved and get to the top of sports. By 1978, three of the top five women listed as “Most Admired” in Seventeen magazine were athletes – a major change from the late sixties when actresses dominated the female scene (Kaplan, 49). Mothers during this time, who grew up in a different era where sports were not meant for women, began to realize the massive impact of sports as well. One mother quoted this about her daughter playing tennis: “She’s not the best one out there and she’ll never win a fortune, but tennis is going to make her a real person. She’s learning to take the hard knocks as well as the breaks. What more can I want from sports for my girl?” (Kaplan, 173). The photo above from Kaplan’s book illustrates this idea as well (Kaplan, 200).

With this newfound respect and realization of the powerful impact of sports, women began to get involved and get to the top of sports. By 1978, three of the top five women listed as “Most Admired” in Seventeen magazine were athletes – a major change from the late sixties when actresses dominated the female scene (Kaplan, 49). Mothers during this time, who grew up in a different era where sports were not meant for women, began to realize the massive impact of sports as well. One mother quoted this about her daughter playing tennis: “She’s not the best one out there and she’ll never win a fortune, but tennis is going to make her a real person. She’s learning to take the hard knocks as well as the breaks. What more can I want from sports for my girl?” (Kaplan, 173). The photo above from Kaplan’s book illustrates this idea as well (Kaplan, 200). As noted in previous posts, J.A. Mangan’s and Roberta Park’s From Fair Sex to Feminism (seen to the left) highlights how the great female athletes of America always risked being considered a freak, or eccentric and a tomboy.

As noted in previous posts, J.A. Mangan’s and Roberta Park’s From Fair Sex to Feminism (seen to the left) highlights how the great female athletes of America always risked being considered a freak, or eccentric and a tomboy.

Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano describe the circumstances of the match well in their book Playing with the Boys. King was about to face Riggs in a $100,000 winner-take-all tennis match. Riggs at this point was “an over-the-hill 1939 Wimbledon champion who appeared goofy and cocky” as he baited King into accepting the match (McDonagh and Pappano, 31). Claiming men wrote him fan letters about the match and constantly surrounding himself with sexy young women, Riggs had the intention of putting King “in her place” (McDonagh and Pappano, 32). Riggs was a 55-year-old former champ, while King was a 29-year-old at the top of her game and number one in the world for women’s tennis. Nonetheless, in 1973, this was a time when virtually all males were deemed superior to any female in sports. It was a symbolic event. The photo above depicts King during this match (Collins, 45).

Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano describe the circumstances of the match well in their book Playing with the Boys. King was about to face Riggs in a $100,000 winner-take-all tennis match. Riggs at this point was “an over-the-hill 1939 Wimbledon champion who appeared goofy and cocky” as he baited King into accepting the match (McDonagh and Pappano, 31). Claiming men wrote him fan letters about the match and constantly surrounding himself with sexy young women, Riggs had the intention of putting King “in her place” (McDonagh and Pappano, 32). Riggs was a 55-year-old former champ, while King was a 29-year-old at the top of her game and number one in the world for women’s tennis. Nonetheless, in 1973, this was a time when virtually all males were deemed superior to any female in sports. It was a symbolic event. The photo above depicts King during this match (Collins, 45). King’s rising popularity following this match was evident in social media as well, specifically in Ms. Magazine – a popular feminist periodical at the time. King received so much national attention for her match that Ms. made her the cover of their 1973 July edition, entitled “Billie Jean Evens the Score”. The cover is posted to the right, showing a beautiful photo of King smiling. The title article associated with King allowed for the female society to really get to know their newfound hero (Collins, 39). She comments on how she wasn’t focused on a family at this time, and she never smoked. More importantly, King used this article as an opportunity to promote female power. As she says, “I keep telling the girls… we’re still getting hassled by male officials, and we still have to fight twice as hard as the men to get fair treatment. We haven’t made it yet,” following her win (Collins, 101). King remained focused on grabbing the young girls and making sure they felt liberated from men’s grasp on the tennis and sporting world. She wanted to make a change for all females, and never felt satisfied with her efforts.

King’s rising popularity following this match was evident in social media as well, specifically in Ms. Magazine – a popular feminist periodical at the time. King received so much national attention for her match that Ms. made her the cover of their 1973 July edition, entitled “Billie Jean Evens the Score”. The cover is posted to the right, showing a beautiful photo of King smiling. The title article associated with King allowed for the female society to really get to know their newfound hero (Collins, 39). She comments on how she wasn’t focused on a family at this time, and she never smoked. More importantly, King used this article as an opportunity to promote female power. As she says, “I keep telling the girls… we’re still getting hassled by male officials, and we still have to fight twice as hard as the men to get fair treatment. We haven’t made it yet,” following her win (Collins, 101). King remained focused on grabbing the young girls and making sure they felt liberated from men’s grasp on the tennis and sporting world. She wanted to make a change for all females, and never felt satisfied with her efforts. She was constantly traveling around the country, making appearances on different news outlets, and promoting female athletes (Collins, 103). This quote from this article, to the right, highlights her constant fight amidst the discrimination (Collins, 103).

She was constantly traveling around the country, making appearances on different news outlets, and promoting female athletes (Collins, 103). This quote from this article, to the right, highlights her constant fight amidst the discrimination (Collins, 103). Nikki Giovanni, to the right, is one of America’s foremost poets who writes about those who fought for social justice, such as Martin Luther King Jr., and, of course, Billie Jean King. Giovanni felt outrage over the palimony suit against the tennis superstar made by her secretary Marilyn Barnett in 1981, revealing their hidden love affair during the 1970s. In her 1993 poem “Mirrors (for Billie Jean King),” Giovanni expresses outrage over this lawsuit and her anger over King’s admitting her affair was a mistake. King was an American idol and female hero at this point, and Giovanni felt King’s sexuality strengthened her position in society and aided her cause to fight for women’s equality.

Nikki Giovanni, to the right, is one of America’s foremost poets who writes about those who fought for social justice, such as Martin Luther King Jr., and, of course, Billie Jean King. Giovanni felt outrage over the palimony suit against the tennis superstar made by her secretary Marilyn Barnett in 1981, revealing their hidden love affair during the 1970s. In her 1993 poem “Mirrors (for Billie Jean King),” Giovanni expresses outrage over this lawsuit and her anger over King’s admitting her affair was a mistake. King was an American idol and female hero at this point, and Giovanni felt King’s sexuality strengthened her position in society and aided her cause to fight for women’s equality. In her poem, Giovanni writes: “The face in the window… is not the face in the mirror… Mirrors aren’t for windows… they would block the light…” (lines 2-3). Giovanni is metaphorically juxtaposing mirrors and windows to describe her feelings that a person’s private and public life are not the same. A mirror allows someone to see into a person’s private life, while a window allows someone to see into someone’s public life: “Windows / show who we hope to be… Mirrors reflect who we are…” (lines 3-4).

In her poem, Giovanni writes: “The face in the window… is not the face in the mirror… Mirrors aren’t for windows… they would block the light…” (lines 2-3). Giovanni is metaphorically juxtaposing mirrors and windows to describe her feelings that a person’s private and public life are not the same. A mirror allows someone to see into a person’s private life, while a window allows someone to see into someone’s public life: “Windows / show who we hope to be… Mirrors reflect who we are…” (lines 3-4). Finally, the poem urges King to not regret who she is and the love she felt during this time for another women. She writes, “… but It Cannot Be A / Mistake to have cared… It Cannot Be An Error to have tried /… It Cannot Be Incorrect to have loved” (23). Giovanni uniquely highlights her desire to tell King that she made no mistake in loving Barnett by capitalizing each letter . King needs to understand how much she changed women’s lives for the best, and how much she changed female sport culture. The final section of the poem, seen above, exemplifies how much King meant to society in a beautiful way.

Finally, the poem urges King to not regret who she is and the love she felt during this time for another women. She writes, “… but It Cannot Be A / Mistake to have cared… It Cannot Be An Error to have tried /… It Cannot Be Incorrect to have loved” (23). Giovanni uniquely highlights her desire to tell King that she made no mistake in loving Barnett by capitalizing each letter . King needs to understand how much she changed women’s lives for the best, and how much she changed female sport culture. The final section of the poem, seen above, exemplifies how much King meant to society in a beautiful way.