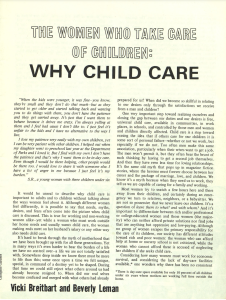

Alice Wolfson’s “Health Care May Be Hazardous to Your Health” was published in the inaugural, June 1970 issue of Up From Under. In this essay, Wolfson critiques the health care system, while also educating women about their various birth control options.

During Second-Wave Feminism, women desired control over their own reproductive process. Consequently, Up From Under’s inaugural issue, published in 1970, features essays that challenge the healthcare system’s conversations about birth control. For example, in one of the essays titled “Health Care May Be Hazardous to Your Health,” author Alice Wolfson describes the healthcare system’s exploitation of women who use birth control pills. The FDA approved birth control pills for nationwide use on May 9, 1960 (History.com Editors). At the time of the FDA’s approval, however, the pill’s side-effects were not fully known. Wolfson warns women about their potential exploitation as guinea pigs. As she writes, “8.5 million American women taking the Pill [were] participating in the largest experiment ever conducted” (Wolfson 8). Wolfson, a pioneer of the women’s health movement, played a pivotal role in Congressional hearings that upended the healthcare system’s deceit about birth control. The hearings began in 1970 when U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson challenged the pharmaceutical industry after reading Barbra Seaman’s book titled The Doctor’s Case Against the Pill (“Senate Hearings on the Pill”). Seaman’s book details the safety hazards of taking “the Pill” through testimonials from physicians, medical researchers, and women who had used oral contraceptives. After witnessing the hearings, Wolfson wrote “Health Care May Be Hazardous to Your Health,” as she felt that although “the Pill hearings in Congress revealed shocking facts about the dubious safety of these drugs,” many women remained uninformed by their doctors (Wolfson 8). Here, she highlights that the system retained control by withholding information from patients. Additionally, in her critique of the healthcare system, Wolfson underlines doctors’ control over abortions, further highlighting women’s lack of control over their own reproductive health. Prior to Roe v Wade (1973), abortions were illegal. In an exaggerated statistic, Wolfson explains the implications of abortion’s criminalization. She proclaims “if the D.C. General had performed the service the women wanted, there would have been 4,000 abortions [of the 5,000 babies delivered in 1968] instead of the seven actually completed” (Wolfson 9). Although Wolfson may exaggerate the number of abortions, a 1965 study conducted by the Planned Parenthood Federation of America suggests that in their sample of 889 women, a total of 74 women “said that they attempted to abort one or more pregnancies; of these, 31 reported the attempt successful” (Polgar 125). Women were consistently denied abortions. Yet, not only did society deny women abortions, they, also, did not provide adequate access to information about contraceptives. Without information, knowledge, or access to their options, mothers and women alike remained at the mercy of a flawed system.

Sources:

Albert, Marilyn, et al., editors. Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 1, 1970, pp. 1–57.

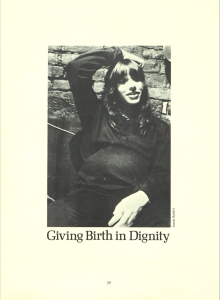

Wolfson, Alice. “Giving Birth in Dignity .” Up From Under , vol. 1, no. 1, 1970, pp. 6-10.

“Senate Hearings on the Pill.” PBS, WGBH Educational Foundation, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-senate-holds-hearings-pill-1970/.

History.com Editors. “FDA Approves ‘The Pill.’” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Feb. 2010, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fda-approves-the-pill.

Polgar, Steven, and Ellen S Fried. “The Bad Old Days: Clandestine Abortions Among the Poor in New York City Before Liberalization of the Abortion Law.” Family Planning Perspectives, vol. 8, no. 3, 1976, pp. 125–127.