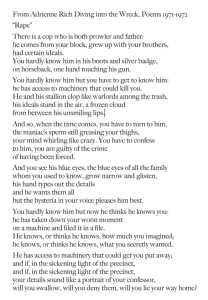

“Rape” by Adrienne Rich was published in one of the first major volumes of feminist poetry, Diving into the Wreck, published in 1971-72, early in the movement. In this seminal volume, Rich addresses one of the key issues of the movement, violence against women and additionally, in this poem, rape jurisprudence as it isolates and degrades victims of sexual violence.

In her poem “Rape,” Rich depicts a rape victim reporting the crime in a precinct to a male cop from the victim’s neighborhood, as she states, “ [he] is a prowler and father…from [the victim’s] block” (lines 1-2). Rich utilizes the cop in the poem to personify the justice system as an unsympathetic and mechanical entity that criminalizes victims for being raped. Rich states, “his hands type out all of the details…on a machine and file[s] it in a file.” Rich creates an impersonal tone through the machinery imagery and the repetition of the word “file” as it insinuates that to the justice system all cases are the same and to be handled in the same automated manner. Rich describes the cop as a “warlord among the trash,” with his, “ideals [standing] in the air…between his unsmiling lips” and possessing “machinery that could kill you” (7-10). This imagery underscores the lack of sympathy within the justice system and the fear it invokes in the victims of sexual violence. Her description of the cop as a “warlord among the trash” also underscores the tyrannical power that the justice system has over the victims and that the victims of sexual violence are lowly trash that don’t amount to anything. Rich continues to write, “you have to confess to him [the cop] you are guilty of the crime of having been forced” demonstrating that the outcomes of rape cases are almost predetermined as the justice system has created and supported a rape culture that criminalizes and blames the victims. The justice system puts victim’s characters on trial and lets rapists walk on the basis that it was not a crime, but rather it was a misunderstanding, or the woman was “asking for it.” Estrich writes in her article in “The Yale Law Journal,” that a verdict in cases of rape, “shifts from whether the man is rapist to whether to woman was raped. A verdict of acquittal…signals that the prosecution has failed to prove the woman’s sexual violation-her innocence- beyond a reasonable doubt”(pg 110). Rich calls attention to this pattern of sexism within the justice system and highlights that, due the ambiguity of the definition of rape in law, the interpretation and verdicts of rape cases are decided on the basis of the male standard of sex and appropriate female behavior not the victim’s story. Furthermore, Rich demonstrates that current rape laws enforce male aggression and contributes to the issue of rape leaving victims isolated and afraid.

Throughout her poem Rich uses the second person “you” to call attention to, as well as to connect with, the myriad of other rape survivors to construct a space and joint consciousness where women and other survivors can feel safe and understood. The repeated use of “you” is indicative of how intimate and personal the discussion of rape is and invites others to join the dialogue; Rich insinuates that rape will never abolished in silence but insists that the current nature of our justice system, as evident in her poem, has created a culture where victims are afraid of coming forward. Rich writes about the cop, “you hardly know him but you have to get to know him: he has access to machinery that could kill you. He and his stallion clop like warlords among the trash” (6-8).

The poem “Rape” by Adrienne Rich was published as a part of her book of poems titled Diving into the Wreck in 1971-72. In her poem Rich depicts the story of someone reporting their rape to a male cop and highlights the corrupt and sexist nature of the justice system.

Additionally by including all readers, not only women and victims of rape, in the “you” Rich invokes a strong sense of pathos. Rich forces the readers into the shoes of the victims in hopes that they better understand how truly helpless and afraid victims are. Not only the the rape occurs but also when they confront the misogynistic justice system. Rich writes, “And so, when the time comes, you have to turn to him [the cop], the maniac’s sperm still greasing your thighs, your mind still whirling like crazy. (11-13). Rich uses the second person to draw the readers into the story and then utilizes evocative and shocking language, “the maniacs sperm still greasing your thighs,” to force the reader to confront the horrifying realities of rape. Rich uses visceral imagery to expose how traumatizing these proceedings are for the victims as they are forced to trust and confide in this unsympathetic “warlord”[cop].

Rich ends her poem with the use of anaphora stating “and if, in the sickening light of precinct, and if, in the sickening light of the precinct” (27-28). The emphasis falls on the word sickening as it creates this again this visceral imagery that makes the reader recoil. Additionally, the two words in the phrase “sickening light” exist in contrast with each other. as light typically insinuates hope, freedom, or a sign that you are going somewhere better while including the descriptor “sickening” creates an uncomfortable dissonance that is indicative of the criminal justice systems treatment of rape. One would like to believe that the justice system is there to protect and support victims of sexual violence but as illustrated in her poem Rich exposes that faith in the justice system is misplaced and present rape law is only further contributing the issues at hand.

Work Cited

Rich, Adrienne. Diving into the Wreck: Poems, 1971-1972. 1st ed. New York: Norton, 1973. Print.