Lydia D Kelly’s untitled poem featured in Women: A Journal For Liberation, redefines motherhood in a nuclear family by addressing the unspoken truth of postpartum depression. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one in eight women experience symptoms of postpartum depression, which include feeling disconnected from their child, doubting their abilities as a mother, and an increase in crying and anger (Depression among Women). During the Second Wave Feminist movement, periodicals began to expose this harsh reality that many women face. In her poem, Kelly battles with her emotions through the journey of motherhood in order to unite women in this common experience.

Kelly’s poem was published in the Women’s Spring 1973 Journal.

Kelly’s three-stanza poem mirrors the three stages of motherhood: pregnancy, birth, and childcare. She starts off by describing her experience with pregnancy as “eager to begin / this tedious business / of dying” (Kelly, 39). Kelly compares the process of motherhood as the “business of dying,” a complicated process that will eventually lead to the death of herself. Pregnancy changes a woman emotionally and physically. It can be an isolating experience, which can lead to the development of postpartum depression. Society has glorified the experience of pregnancy by promoting the beauty of women carrying a child but disregards all negative experiences women face with pregnancy and birth.

Therefore, Kelly continues to describe her birth as parasitic. She shares her draining birth experience as “so you sucked your / mouth until the / liquid disappeared / like my womb, / my youth, / my marriage” (Kelly, 39). The child is the parasite and she is the host–leeching out all she has left. Birth is a life-changing experience that comes with new responsibilities and a new outlook on life. In Kelly’s experience, her birth put an end to her womb, youth, and marriage. Her whole life will now be dedicated to raising her child, slowly losing herself in the process. Like Kelly, many women also are faced with this reality. Society portrays childbirth as a joyous experience for mothers, but ultimately neglects the negative aspects and emotional toll of child-rearing.

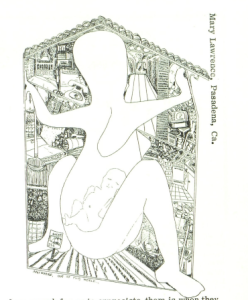

In the same periodical, Mary Lawrence illustrates a distorted figure, crammed inside a house. Inside the figure is a child. Lawrence illustrates the confinement of mothers in the nuclear family. Mothers are physically trapped in a home that is exceedingly demanding.

Kelly ends her poem by sharing the conflicting emotions of being faced with motherhood. Her alternating state of emotions from “I hate you, / I love you, / I wish you were . . / . . asleep” illustrates the common symptoms of postpartum depression (Kelly, 39). Once again, Kelly references the state of dying, but this time hints that she wishes her child was dead. The use of ellipses shows the hesitation of revealing Kelly’s actual meaning behind her emotions. She battles with her creeping thoughts and is afraid of being labeled a “bad mother” or “unloving” to her child.

Postpartum depression, then and now, is an all too common form of depression that women face after having a child. Women who express symptoms of postpartum depression are often labeled as “bad” and “unloving.” Thus, the women’s movement allowed women to express their negative emotions towards motherhood and redefine society’s view of motherhood as burdensome.

Works Cited:

“Depression among Women.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 14 May 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/depression/index.htm.

Kelly, Lydia D. “Untitled.” Women: A Journal for Liberation, vol. 4, no.3, pp. 39.

Lawrence, Mary. “Untitled.” Women: A Journal for Liberation, vol. 4, no.3, pp. 3.

Women: A Journal for Liberation, vol. 4, no.3, Spring 1973.