The recognition of Native women from the past is central to the work of Indigenous feminists. Poet Gayle Two Eagles ties the promise of future generations of Native women to the influence of Native women ancestors within their communities, which has been historically underappreciated. In her poem “The young warrior,” Two Eagles begins with the image of a young warrior who “sees the world through brand-new eyes,” and embodies such promise that the Lakota people can “be proud again” (108). Accompanying the image of a young warrior is the representation of a woman warrior, who fights alongside all warriors as equals, because she too is “proud and strong” (108).

The first half of Gayle Two Eagle’s poem “The young warrior.”

But the woman warrior’s charge is to be fierce in the face of the injustices aimed against her, to combat the traditions “as told by men, / Written in history books by white men” (108). She stands in “Quiet defiance to the men who say, ‘respect your brother’s vision,’ / she mutters, ‘respect your sister’s vision too’” (108). Two Eagles asserts that this vision that Native women carry is not honored within their own communities. The woman warrior is not included in the warrior histories of her people, despite the fact that “She was with you at Wounded Knee, / She was with you at Sioux Falls, / Custer, / And Sturgis, / And has always remembered you, / Her Indian people, / In her prayers.” By including the presence of the Native woman in well-known battles and massacres of Native people, Two Eagles rewrites history through poetry, a powerful practice among Indigenous feminist poets.

The second half of “The young warrior.”

Two Eagles continues to harness the power of truth-telling within a community as she speaks to the extreme violence against Native women, who “were beaten by the men they love, / Or their husbands” (109). By highlighting the dangers Native women face even in their own homes, Two Eagles demonstrates their inherent strength and resilience. She returns to the image of the Native woman warrior, who “gave strength to women who were raped, / As has the Sacred Mother Earth.” Here she makes an important connection between the violation of Indigenous women and that of the land. Both women and land have been violated, but “Sacred Mother Earth” has also been a source of fortitude. Two Eagles invokes a vital characteristic of Indigenous feminism, which is the support cultivated in gathering spaces where Native women voice truths in the language of stories and honor women of the past who survived for their sake. This collective ritual is intrinsically tied to traditions of honoring Mother Earth and the role she plays in sustaining communities as a central part of Indigenous identity and thereby Indigenous feminism.

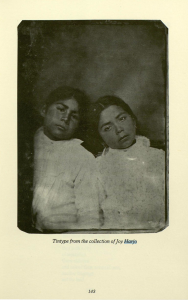

Tintype of Native youth from the collection of Joy Harjo, included in A Gathering of Spirit.

Indigenous identity has been threatened for centuries, but the resistance to discrimination within Native American communities has not always centered Native feminism. Two Eagles turns our attention to the future of Native people and how indigeneity must be centered around women: “The new eyes that once were in awe at what the world had to offer, / Looks down at this new girl child, / The Lakota woman warrior knows her daughter also has a vision” (109). Two Eagles uplifts future generations of young Indigenous women warriors who will make change, gather strength from the earth, and share that strength among each other. She empowers Native women by asserting that Native future relies upon respecting the woman warrior, for she holds the power to foster change, gather the collective, share truths, and make her people proud.

Sources:

Brant, Beth. Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, Iowa City Women’s Press, 1983.

Harjo, Joy. Untitled Tintypes. Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, p. 143.

Two Eagles, Gayle. “The young warrior,” Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, pp. 108-109.