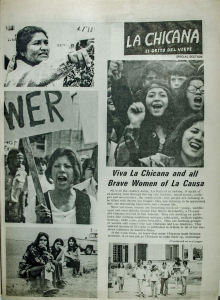

Just as the vitality of El Grito del Norte’s feminist awakening can be traced to the mentorship relations that introduced the young Chicana contributors to the in’s and out’s of the writing and printing process, Chicana feminist scholar Maylei Blackwell describes how new feminist visions came to fruition in Chicana studies programs across the United States in her chapter “Contested Histories: Las Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, Chicana Feminisms, and Print Culture in the Chicano Movement, 1968–1973.” Veteran Chicana activists took residency at universities and enlisted a new generation of Chicana student change-makers in the struggle to create a lasting assertion of their identities, struggles, and cultures against the tides of erasure (Blackwell 62) . This movement was especially noticeable in California, where students at San Diego State University, California State University, Fresno State College, and Stanford University, among others, formed organizations, courses, newsletters, and support groups in recognition of the shortcomings of the broader Chicano movement and the white feminist movement (Blackwood 64). For example, at California State University Long Beach in 1971, Anna Nieto-Gomez and a group of Chicana undergraduates, together forming the feminist student newspaper Hijas de Cuauhtémoc (Blackwood 69). This publication grew into the landmark 1973 journal Encuentro Femenil, published in two numbers in the Los Angeles metropolitan area and considered one of the first true Chicana feminist periodicals (Del Castillo).

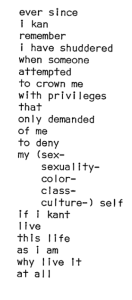

Elsewhere, in her 1971 class “Imágenes de La Chicana” at Stanford, Rita Sánchez (and later Carol Castillo) encouraged her 32 undergraduate students to immerse themselves in the expression of their experiences as Chicana women, and their collaboration resulted in a “collection of student writings in a first attempt at a Chicana journal at Stanford” (Sánchez 2). The first edition of Imágenes de la Chicana incorporates a variety of poetry, essays, vignettes, and research projects, and Sanchez states in its preface that the text is a response to the lack of writings by or about Chicana women (3). This work, then, intends to stir the creative energy of the Chicana woman, wherever she may be. The energy in question is on full display in Dolores Rays’ poem “Descubistre,” in which the speaker stumbles across the beauty of the culture she has been taught to suppress and is overcome with the urge to do everything all at once:

to scream

to cry

to yell

to fight

to hate

to blame

to condemn

to think

to reflect

to ponder to understand

to read

to learn

to teach

to sing

to jump

to dance

to drink

to smoke

to party

to smile

to laugh

to talk

to love. (Rays 8)

The configuration of these single lines reads as an incantation of divine power, as if it is a command from the ancestors of long ago, instructing the women to bask in the newfound warmth of her soul. Rays’ speaker concludes by addressing the Chicana subject in the present with her blessing: “Now you are alive not merely in existence. Now you can live not merely function. Now you are living” (9). Here, Rays urges the reader to join the battle to defend La Raza, for the revelations of identity that occur outside of the “white-oriented society” are freeing. Free of discrimination, of humiliation, of abandonment and isolation, “this new discovered world” consists of the company of women who have understood the weight of the Chicana’s burden (9).

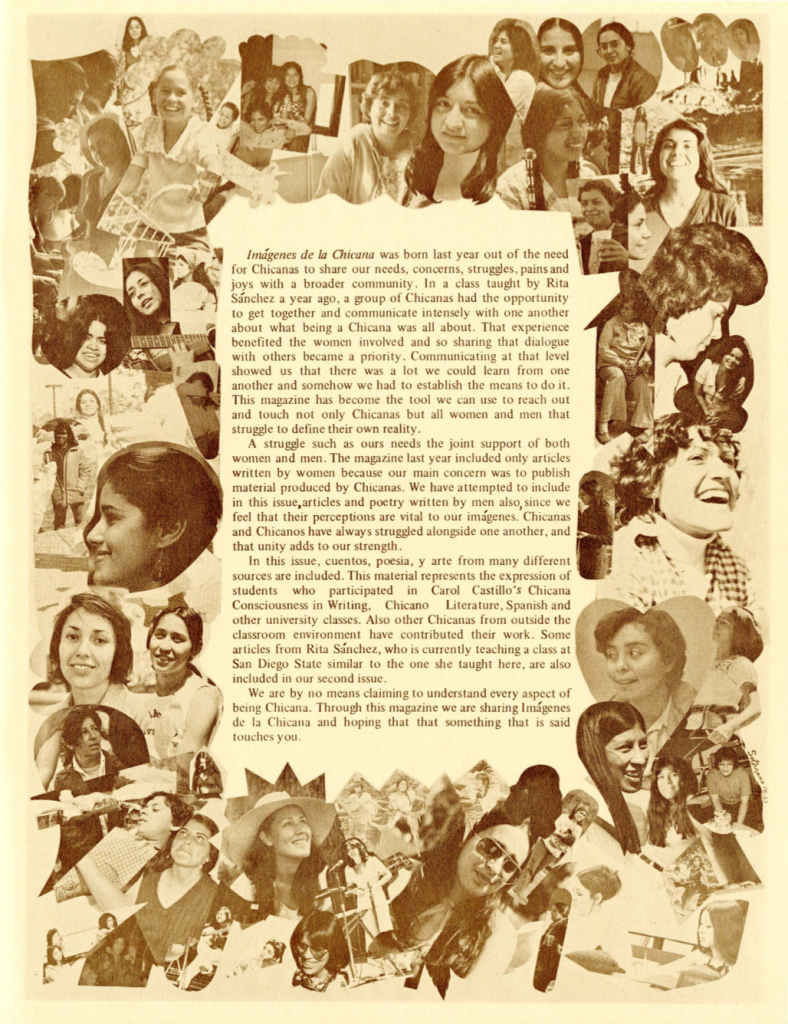

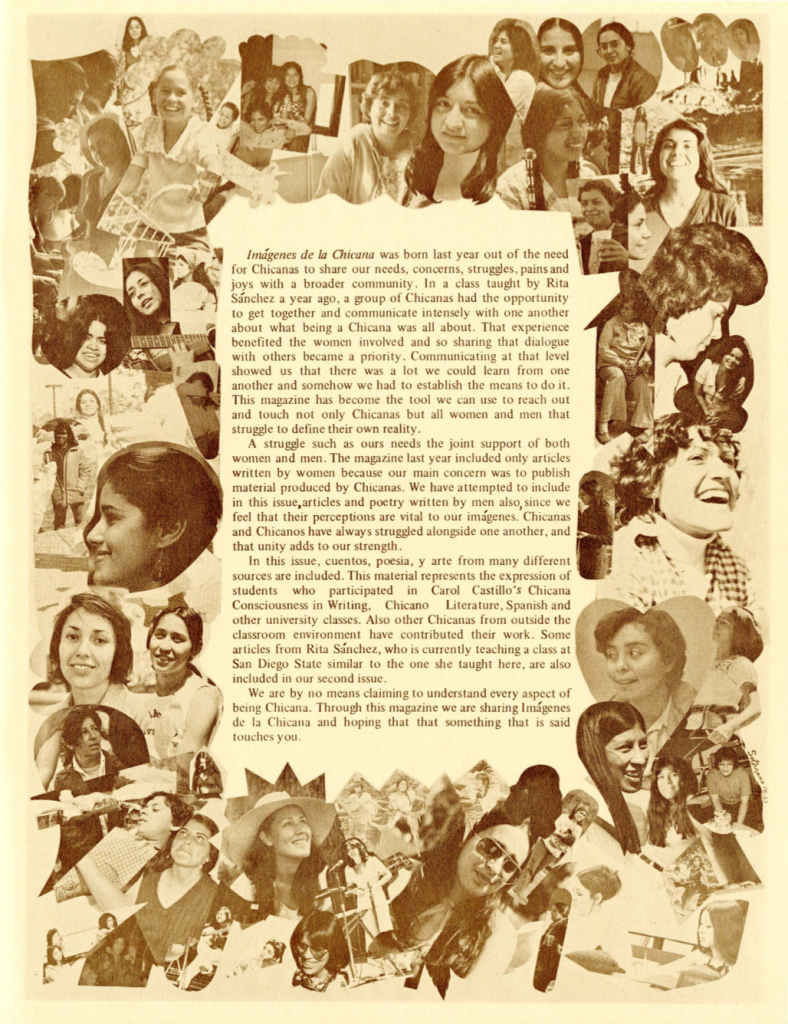

The editorial statement page for the second and final issue of Imágenes de la Chicana (1972). Framing the statement are images of the women who contributed to the publication and to the broader goal of reframing Chicana feminism.

In the second and final edition of Imágenes de La Chicana, the editors decide to appeal to a Chicano audience alongside the Chicana audience clearly addressed in the first issue. They assert in the preface, “Chicanas and Chicanos have always struggled alongside one another, and that unity adds strength” (Imágenes de la Chicana). Although the statement appears to be a compromise that weakens the independent feminist ideas of the original issue, it is underpinned by the idea that the liberation of Chicana women, at least in the eyes of the editorial staff, remains the primary objective, given that this cause lacked support from Chicano political organizations on numerous occasions. Thus, instead of limiting themselves to the existing boundaries of the Chicano movement, the students are challenging their Chicano brothers to adopt their cause and stand in solidarity with them. In this issue, Debbie Reed’s poem “Recuerdos de mi Barrio” describes a challenge that does indeed affect the entire Chicana/o community, namely “Anglo” infiltration (27). As “teachers, preachers, English majors / City planning, Urban renewal / McDonald’s, 7-11’s, and parking lots” invade the spaces that have been carved out by people who “can’t turn back to our fathers,” it is the most the speaker can do to hold on to at least the Spanish language, “nuestra lengua” (Reed 27). Since the patterns of colonization and of modernized removal repeat themselves as the “past and present mingle as one,” Reed, through her speaker, emphasizes how important it is for the Chicana/o community to resist, to keep its language, its meaning, its pride, its culture, its very blood (27). This edition of Imágenes de La Chicana serves as a reminder of the oppression of the Chicana woman on account of her sex, which exists in addition to the oppression faced by Chicano/a men and women on account of their race.

Works Cited:

Blackwell, Maylei. “Contested Histories: Las Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, Chicana Feminisms, and Print Culture in the Chicano Movement, 1968–1973.” Chicana Power! : Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement. 1st ed. Austin: U of Texas, 2011. Chicana Matters Ser. pp. 59-84.

Del Castillo, Adelaida R. “Encuentro Femenil.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. Oxford University Press, Oxford Reference. www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156003.001.0001/acref-9780195156003-e-266

Imágenes de la Chicana, vol. 1, no. 2, Chicano Press at Stanford, 1972, p. 3.

Rays, Dolores. “Descubistre.” Imágenes de la Chicana, vol. 1, no. 1, Chicano Press at Stanford, 1971, pp. 8-9.

Reed, Debbie. “Recuerdos de mi Barrio.” Imágenes de la Chicana, vol. 1, no. 2, Chicano Press at Stanford, 1972, p. 27.

Sánchez, Rita. Imágenes de la Chicana, vol. 1, no. 1, Chicano Press at Stanford, 1971, pp. 2-3.