Sustainability of Farming in Zangskar

The effects of climate change on Zangskari agriculture are dramatic. When scarcity of summer meltwater led farmers to leave more and more fields fallow each year, eventually villagers in Zangskar’s oldest settlements, Kumig, began building a new village on the Zangskar river plain far below their old village.

Even after more than a decade of construction, the new irrigation canal provided only limited relief as it was destroyed by landslides and did not produce as much water as expected. Furthermore new fields are hardly as fertile as the older fields whose soil has been nourished by centuries of compost and careful management.

Given that Zangskari agriculture is entirely dependent on meltwater from glaciers and snowfields, the shrinking of glaciers and snowfields due to rising temperatures are wreaking havoc on local livelihoods.

What will happen in Zangskar as more fields are left fallow, young people no longer dream of farming, and droughts elsewhere in India reduce the agrarian surpluses that provide food rations and supplement the Zangskari diet?

Locals are questioning the sustainability of farming in the most arid villages given the shifting timing and quantity of snowmelt available for irrigation. Less snowmelt that arrives earlier than in the past can mean insufficient irrigation water during two critical periods of Zangskar’s growing season:

- Too little meltwater in April & May that kills or damages tender seedlings during the critical first watering period

- No water to complete the growing season in August leading to stunted yields

The reduced yields of Zangskar’s three major crops–-barley, wheat, and peas––and smaller harvest of supplemental crops like pulses, potatoes, cabbages, spinach, and onions, leave Zangskaris vulnerable to food shortages during six winter months when roads are closed and little food is imported in remote villages across the region.

In Sendo, like Kumig, farmers left half their fields fallow in the summer of 2001 because there was not enough meltwater for irrigation.

Rising temperatures contribute to shifting monsoon patterns that produce extreme cloudbursts resulting in flooding, landslides, and the occasional glacial lake flood outburst (GLOF).

Dramatic floods in Ladakh in 2015, 2014, 2010, and 2006 destroyed lives, fields, houses, and bridges across the region, in addition to creating anxiety about future disasters.

The 2010 flood in Leh killed at least 255, caused 1000 injuries, and caused 1,330,000,000 Rs in damages.

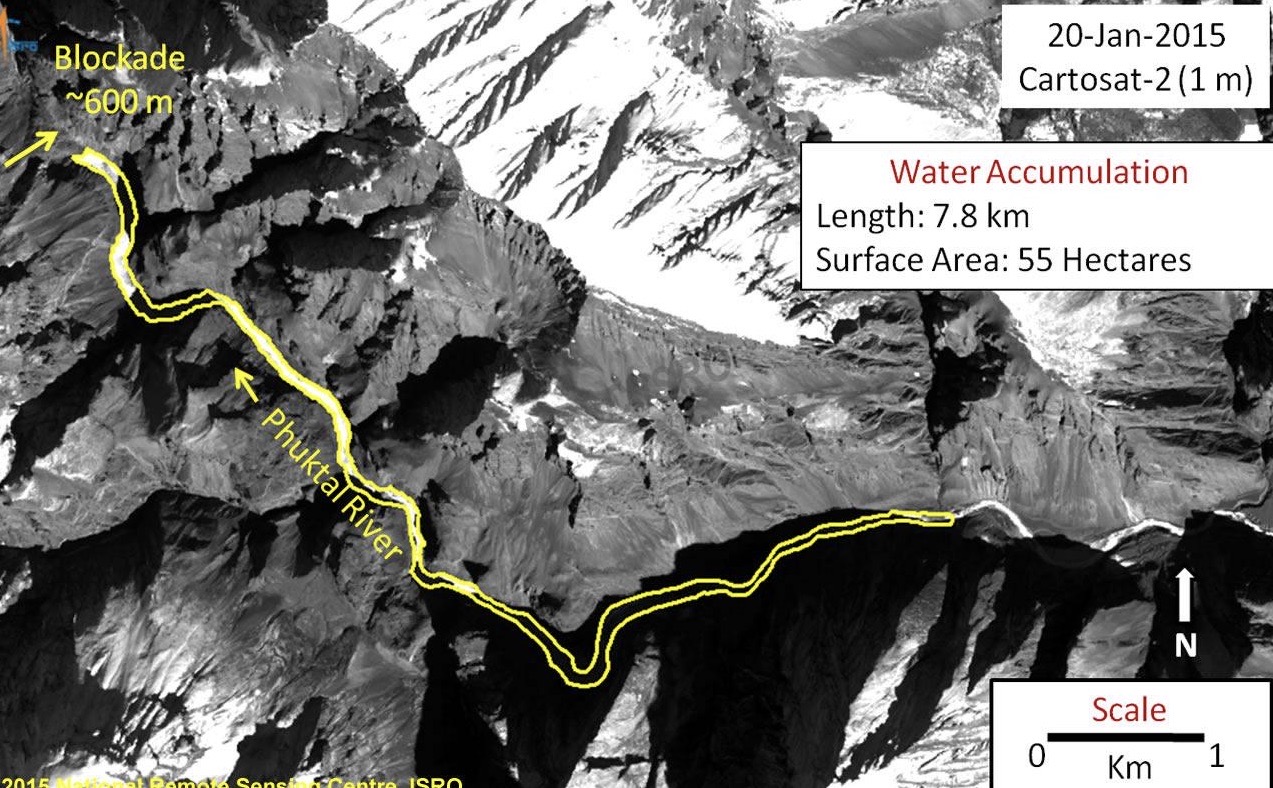

The 2015 flood in Zangskar resulted from a winter landslide near Phugthal monastery that dammed up the Tsarap river for months before bursting in May. For months, local villagers begged state and national government officials to intervene, to no avail.

When the dam burst and floods destroyed schools, bridges, and fields lying along the Tsarap river valley, Zangskaris learned a valuable lesson. They are responsible for their own safety and disaster management plans.

These floods and landslides can cause loss of livelihood that persist for years. Fields and houses that are built up and nurtured over generations and centuries in Ladakh are swept away in less than an hour.

When it proves impossible to remove the debris, villagers may look to resettle elsewhere. Yet cultivable land and irrigation water are already in scarce supply in Ladakh.

Even when water and land is available, it can take decades for newly created fields to produce yields similar to those from older fields whose soil nutrients benefitted from centuries of organic matter and careful tending.