Buddhist Statuary

Background of Buddhist Statuary

Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the year 538 when the ruler of Baekje, a Korean kingdom, brought an image of the Buddha to the Japanese Emperor Kimmei. Immediately, there was a controversy over whether or a “foreign cult” should be accepted. However, a highly influential clan known as Soga liked Buddhism, so the emperor deferred the matter to the Soga clan.

About 40 years later, Prince Regent Shotoku (A.D. 574–621) was appointed regent to the Empress Suiko, and made Buddhism the official religion.

In the late Heian period, Pure Land Buddhism reached Japan and skyrocketed in popularity. Pure Land Buddhism emphasizes a faith in Amida. By reciting his name, buddhists believed that they were purifying their soul, enabling them entrance to Heaven. At this time, there was a noticeable increase in demand for Buddhist statues.

Buddhism offered both moral and intellectual benefits which Shinto lacked and it was these cultural learnings that attracted the court. Since Japan did not have a formal written language at the time, all of the Buddhist scriptures that were used were in Chinese. Thus at first, Buddhism was almost exclusive to the court families. However, during the Kamakura period, Buddhism’s popularity ballooned to reach all people in all class levels.

Types of Statues

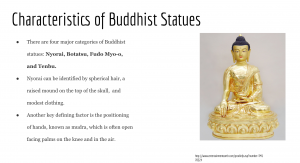

Buddhist statues can be divided into three types: nyorai, botatsu, myō-ō, and ten. They exist in a hierarchy, descending from that order according to the roles they play.

Characteristics of Nyorai Statues

- In Gandhara, the primary origin buddhist statuary, nyorai statues have hair wavy hair, but in Japan, the hair resembles knots known as rahotsu.

- There is raised mound on the top of the skull to indicate a higher level of wisdom.

- Clothing consists of two pieces of cloth, mo for the lower body and kesa for the upper body. The sparsity in clothing represents the lack of material desire.

- The types of nyorai statues are shaka nyorai, yakushi nyorai, amida nyorai, and dainichi nyorai. They can often be distinguished by the position of the statues’ hands, known as mudra.

Characteristics of Bosatsu Statues

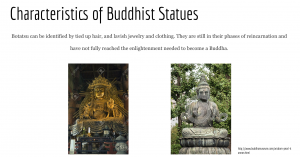

- Bosatsus are said to be in practice for becoming an enlightened nyorai.

- Their hair is long and tied up, and their clothes are very luxurious, as they are modeled on the appearance of a prince. They can be distinguished by their many accessories.

- Similar to nyorai, they also wear a mo on their lower half, and on their upper half is a piece of cloth called the johaku, draped across their shoulder. In addition to the johaku, a tenne is draped over the shoulders.

- The types of bosatsu are miroku bosatsu, shō kannon, jūichimen kannon, senju kannon, monju bosatsu, fugen bosatsu, and jizō bosatsu.

Characteristics of Myō-ō Statues

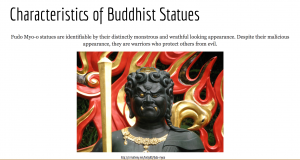

- These statues have very distinct faces, which resemble angry monsters. They are intimidating, as they are said to be the last resort in protecting those who could not be protected by nyorai or bosatsu.

- These statues often have multiple faces, hands, feet, and eyes.

- The types of myō-ō statues are the seitaka dōji, fudō myō-ō, kongara dōji, godai myō-ō, gōzanze myō-ō, gundari myō-ō, daiitoku myō-ō, kongōyasha myō-ō, and aizen myō-ō.

Characteristics of Tenbu Statues

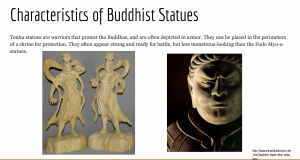

- The ten are known as deities who guard the Buddha’s Law. The two types of ten are gohōshin, who protect the Buddhas, and fukutokushin, who make people happy.

- Ten statues can be distinguished by bodies, which often seem to be half human and half animal. They can also frequently be depicted as wearing armor.

- There are many more ten statues than there are other types.

Materials

The materials used in creating these buddhist statues has differed throughout the years. This is based on which materials were most readily available. The first statues brought to Japan were said to be made in Korea. They were made of gilded bronze, known as kondōbutsu in Japanese.

Later on during the Nara period, imports from China grew, and Chinese statues became popular. These statues were made using clay, known as sozō, in a technique known as kanshitsuzō. This technique involves soaking hemp cloth in lacquer and layering it into the desired shape, then letting it dry.

When buddhist statuary began to grow amongst Japanese artisans, woodcarving became the primary method of creation. Japan has a lot of forest space and trees, which made wood carving a convenient choice. The technique, ichibokuzukuri, entails carving out a statue from a single block of wood.

Layout of Statues in Shrines

Triads

Statues will often be arranged in triads. The centerpiece or the main focus of the triad is known as the chuson. The right and left flanks are known as the wakiji positions. These positions are often assigned in hierarchy order. For example, if a nyorai is chuson, it is likely that bosatsu will be in the wakiji positions, protected by ten statues.

Yakushi Triad

This triad features the yakushi nyorai as the chuson, with gakko bosatsu and the nikko bosatsu in the wakiji positions. This is a very basic and standard format.

Shitenno Tetrad

This tetrad features both nyorai and bosatsu.

Post-Trip Discoveries

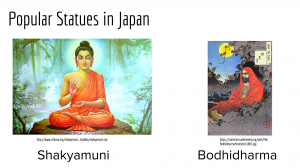

Popular Statues in Japan

- The shakyamuni is the most revered Buddha, known for accomplishing complete enlightenment and reaching Nirvana. This means that throughout his many incarnations on earth of helping others, he finally reached his last incarnation and died at full enlightenment.

- The Bodhidharma is a monk who is known for undergoing a training so serious that he meditated until his limbs atrophied, which prevented him from moving.

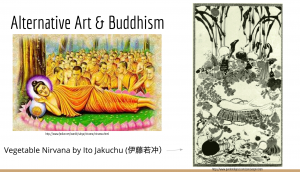

Alternative Art & Buddhism

- The nirvana scene is a depiction of Buddha’s death, with his disciples mourning in the background. It is meant to be a more serious work of art that depicts a heavy loss. Ito Jakuchu was born into a vegetable farming family, and tried to incorporate those elements into his picture. In the center, Buddha is depicted as a daikon radish, which is a very significant crop in Japan. However, one can imagine that something like this, if applied to a Christian depiction of Jesus on the cross, would be extremely blasphemous and poorly received. This painting however was well received and Jakuchu remains a famous and well respected artist. Therefore, in terms of religious-based arts, there is a bit more room for expression with Buddhism.

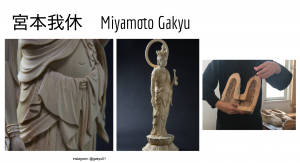

How does Miyamoto utilize the traditional?

Miyamoto is well-trained and has a good background in traditional styles. He has a background in studying fashion, which helps him to craft beautiful and intricate garments for the statues.

Furthermore, he is involved in doing restoration work on statues in temples. He says that this allows him to improve his skill within traditional crafting, as he is able to observe firsthand the techniques of his predecessors.

How is Miyamoto creating his own modern approach?

Sculptures have traditionally been more serious-looking, and placed in shrines. They tend to require a visit to a shrine, since many people don’t have them in their homes.

In the fast paced world of today, people generally are short on either time or money, which prevents them from really forming an interest in these statutes. Someone either needs time to visit a shrine, or money to buy their own statue.

Miyamoto’s goal is to maintain these traditions while creating a new type of art that is both accessible to younger generations, and reflects his uniqueness as an artist.

His sculptures are a lot less traditional in appearance. They have cute faces, bright colors, and are small and portable. This is the aesthetic that Miyamoto is using to reach the attention of younger audiences. His thinking was that if they pick it up because it’s cute and take it home, maybe they will continue to look at it, and it will inspire a deeper curiosity about the statues and make them wonder more deeply about their symbolism.

They also have an aspect of practicality. The everyday worker or a college student like myself can rarely invest in something that doesn’t serve a practical purpose in life. This is why Miyamoto designed these sculptures to serve as paperweights or flower vases as well.

Despite this 21st century approach to his art, Miyamoto is still deeply invested in the traditional and takes a deep interest in religious concepts. Take for example, the dharma statue. There are no atrophied limbs in this case, but instead, there are mushrooms growing on his head to symbolize his lack of movement. I asked Miyamoto if the tradition and religious meaning could ever be fully removed from the statues. His response was that without tradition, there is no longer any meaning.

Although Miyamoto’s art seems alternative at first, his overarching goal is still to convey the same stories and meanings that any traditional statue would bear. He is deeply invested in his work, spends a lot of time researching, and carefully constructs an element of deeper meaning to each of his pieces. In this way, he is fully capable of packaging tradition in a way that is palatable for modern tastes.

Reflections

I appreciate that Miyamoto has such a strong dedication to preserving the tradition of his work. When constructing religious art, as a religious person myself, it is always so important to preserve the true meanings and purposes conveyed by that religion. His idea that religious art is meaningless without tradition is one I agree with– what’s the point of depicting a religious figure if you are not trying to communicate the purpose of that character?

Furthermore, I appreciate that he puts elements of himself into his art. Before this trip, I thought that Buddhist statuary was about precision. I thought that the goal was just to make a statue as perfectly as trained, but I realized after going to Kyoto that there is so much room for an artist’s personal touch. Miyamoto puts his own touch on his art through his intricate fashion designs, and by showing his Christian influences. He said himself that Christianity was a strong influence of his in his art, which can be seen in his Kannon-style depictions of the Virgin Mary.

Sacred Mirrors

Bronze mirrors have a long history, with examples ancient Egyptian examples dating back at least 5,000 years. They were introduced to Japan about 2500 years ago through China. At first, they were used in burial rituals but eventually became associated with Buddhism and Shinto. Since then, they’ve played prominent roles in Japanese mythology and religion. The most famous mirror, Yata-no-Kagami, is said to have been used to trick the sun goddess Amaterasu out of her cave, restoring light to the world. It’s thought that mirrors act as intermediaries between the world humans live in and the spirit world. They are also seen as truthful because they reflect everything, good and bad, accurately.

Leading up to the Meiji restoration and industrialization, bronze mirrors were used for a large variety of purposes. In addition to being religiously significant, they were relatively common daily objects. According to Yamamoto-san, People would use them as practical mirrors or fashion accessories. As new methods for making mirrors became more competitive, bronze mirrors fell out of favor with most audiences. Temples and shrines soon represented most of the demand for bronze mirrors in Japan. More recently, demand from these religious institutions has weakened. This has left bronze mirror makers in a difficult position.

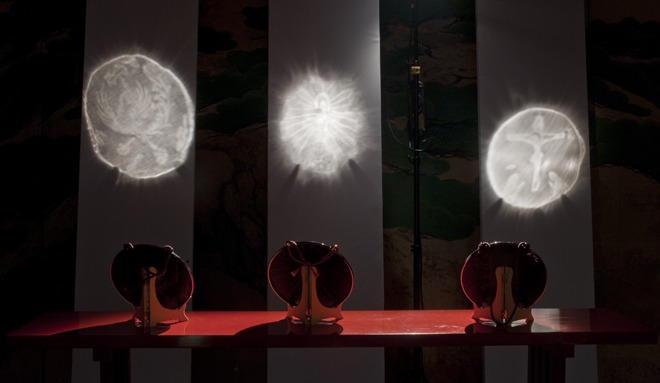

Makkyo

Makkyo are a subset of sacred mirrors that feature a symbol in relief on one side and a highly polished surface on the other. As a result of their special creation process (detailed below), when light is shone on a makkyo, the reflection is an approximation of what’s in relief on the opposite side.

The reflections of three makkyo

This otherworldly effect furthers the sense that mirrors interact with the spirit world. Makkyo are very rare because they are extremely time consuming and difficult to produce; only two people are known to make them. The overwhelming majority of sacred mirrors seen in homes, temples, and shrines are not makkyo or show only very weak makkyo-like effect. Because Shinto shrines do not feature imagery of their gods, virtually none of them contain makkyo. More commonly makkyo depict figures from Christianity or Buddhism. Makkyo have been especially important to the Christian community during times of persecution (during the 17th century mostly) as a means of concealing their worship. Christian imagery would be in relief on the back of the mirror and only under strong light would the image be visible in the reflection.

Making Makkyo

Makkyo are cast from bronze and therefore require molds which are made of a clay and sand mixture. Once the molds are made, it’s possible to make many replicas of the same mirror. According to Yamamoto-san, it costs ten times as much to make a mirror from scratch as opposed to one from a mold. Once the mirror is cast it must be carefully polished. This is done initially by scraping material off and is finished by polishing with a grindstone and eventually wet polishing with charcoal. This process is quite difficult as the mirror must be very thin in order to function correctly. Once the polishing is complete the mirror is covered with a mercury alloy that causes it to distort more in thinner sections, giving rise to the special reflective property.

Yamamoto-san’s Work

Yamamoto-san has continued his grandfather’s tradition of makkyo mirrors, but has also taken innovative steps to adapt to changing markets. One of the problems he’s working to address is how long it takes him to create a single mirror. Because traditionally-sized makkyo mirrors are so time-consuming to make, they are quite expensive. To bring his art to a larger audience, Yamamoto-san has been experimenting with making smaller mirrors, such as the one in the necklace below.

He’s also been working to break traditional boundaries of how and where sacred mirrors would be displayed. His work has been shown at various art exhibitions and he’s even done installation pieces for a hotel. Yamamoto-san has also tried using crowdfunding and the internet to promote his work but admits that he has a ways to go before this is viable.

The Future of Sacred Mirrors

Something that impressed me about the sacred mirrors was how many different groups of people had formed connections with them over the years. There’s a history of bronze mirrors in a number of ancient cultures. Just in Japan, they were adopted by Christians, Buddhists, followers of Shinto, and for a time the general public. I think this reveals a widespread attraction to bronze mirrors and what they represent. Many people in our group were also fascinated by the mirrors that Yamamoto-san had made. The ability for an art piece to appeal to so many people from so many cultures is a rare trait that should be taken advantage of. It seems like a logical next step to introduce makkyo mirrors to the international art community. Perhaps then the craft could be revitalized and preserved by pockets of new practitioners across the globe. In a way it’s even easier to present such work to foreigners; they may have fewer expectations and the whole concept of sacred mirrors could be fresh and intriguing. The infrastructure is present to facilitate such an expansion, but it would take some effort. Hopefully we see movement in this direction from Yamamoto-san and other craftsmen.

Potential Questions

For Miyamoto-san:

Miyamoto went to school to become a fashion designer before switching his interests to buddhist statuary. He was formally taught in the art of making Heisei-period statues.

What was the process for you to become a statue maker?

What qualities do you think a person should have before becoming a statue maker?

Do you consider yourself a religious person?

Do you think a deep involvement in Buddhism is necessary to become a statue maker?

What do you think current perceptions of religion are in Japan? Do you think buddhism is declining in popularity?

Would you say that your art has adapted at all to fit the current interests of society?

Would you consider yourself a traditionalist or a modernist? For example, do you ever like to explore using different materials or do you stick to the traditional methods?

Which materials do you prefer working with?

Do you ever put a personal touch on your statues?

What do you think makes Japanese buddhist statues unique to Japan?

For Yamamoto-san:

Materials seem to be important in creating makkyo. All that we have seen have been made of bronze and we’ve heard that you need a rare kind of charcoal for polishing. Is it possible to substitute any of these materials?

You said in another interview that makkyo aren’t popular in Shinto shrines because Shinto gods exist in natural objects and aren’t typically depicted like pictures of Buddha and Jesus might be. Have you ever made a makkyo for a Shinto shrine? What appeared on it?

What do you hope for the future of makkyo making? Does it seem like there’s a way to reach a large enough audience while retaining your traditional methods?

Are most commissions now still religious in nature or have you seen a shift in subject matter?

What would you say about the mass production of mirrors? How does your craft interact with it?

Have you ever done a mirror for yourself or without commission?

Part of the appeal of makkyo is that they’re so rare. If people continue making them are you worried they might gradually lose their “magic”?

Are any of the makkyo you’ve made on permanent public display (in a train station, public square, etc.)? Would you be interested in doing a project like that or would it not be consistent with your goals?