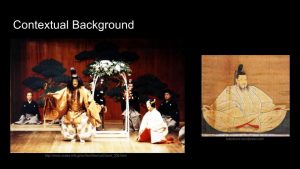

•Origins of Noh (能)•

- Noh was created for and under the patronage of samurai rulers and aristocracy during the Muromachi Period, which began app. 200 years after the heian period (1338-1573) and finds influence in bugaku, the imperial court dance of the heian period. This influence came in the form of “jo-ha-kyū”

- The most creative period of development was during the 14th and 15th centuries under the patronage of the Ashikaga rulers, particularly Yoshimitsu, and largely the work of the oya-ko combo Kannami and Zeami.

- Noh follows the “jo-ha-kyū” (序破急) Japanese principle of aesthetics (introduction, development, quick movement or finale) on all levels.

Five Schools of Noh:

- Kanze (観世流)

- Hōsho (宝生流)

- Komparu (金春流)

- Kongō (金剛流)

- Kita (喜多流)

•Religion and Noh•

There are two opposing opinions on Noh’s connection to Buddhism in japan (one on either extreme), but influence can’t be outright denied. There are some who argue also that there is strong connection between Noh and Shintoism.

- Noh in itself does not have a religious function.

- Some plays present Japanese deities and some evoke thoughts of shamanistic ritual (Shinto), while a great many are permeated with obviously Buddhist language.

- Zen Buddhist ideology can be seen in structure of typical Noh play: a play is divided into 2 phases, between which a switch from present to past may occur. In the first phase, the shite appears in reincarnate form (after death and rebirth). In the second phase, the shite reappears in “true identity” (the form before death and rebirth).

- The Waki is often a Buddhist or Shintoist priest who reveals his identity and tells the audience when and where the drama will take place.

Parallels can be drawn between the kakegoe of Noh performers and the Katsu shouts of Zen Buddhist monks (a shout used to intuitively grasp the state of enlightenment—Satori)

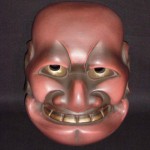

•Masks•

- Noh and Kyōgen masks are made with the same materials

- Woods

- most frequently: hinoki

- occasionally: katsura, honoki, kiri

- almost never used: kusunoki , yanagi, ginnan

- Reproduction

- method devised by Edo mask makers (during Edo it becomes codified)

- patterns of the front and side are cut out

- this method only gives a general shape, to get the right features/spirit is the task of the mask maker

- Backfinishing

- started in Momoyama period

- most masks are finished

- earlier pieces use a simple layer of lacquer

- more complex lacquering techniques come into development later

- (reading note: Kawachi, master carver)

- must be finished in such a way so that the mask makers chisel marks (analogous to signature) are left in view

- Coloring

- also many different methods

- starts with layers of chinese white (a pigment) and glue (nikawa)

- other layers are added and then scraped/smoothed

- the process of painting moves from lighter colors to darker colors

- the smoothing of each layer must be done very carefully to achieve the soft desired look

- especially for masks of women because they are almost completely flat

- after the base coloring is done, other aspects are added

- hair for certain masks

- metal eyes/teeth for demons

Some Noh Masks (nōmen, 能面)

otoko

onna

tobide

ōbeshimi

hannya

- an essential part of noh is the shite’s communing with the mask (they must become one)

- noh, at its core, is a mask drama (simply restating the words in a certain manner is not enough)

- making the mask versatile is a part of noh

- raising the head (and capturing the light) makes the mask look happy

- lowering the head makes the mask look sad

shadows

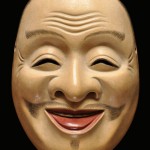

Some Kyōgen Masks (kyōgenmen, 狂言面)

saru

buaku

otafuku

ebisu

- the origins of the development of kyōgen masks are unknown

- legend/rumor that noh mask makers would make kyōgen masks as a release

- noh is a mask-drama, while kyōgen is a comedy of words.

- while noh focuses on an idealized grace and otherworldliness, the spirit of kyōgen comes from the goodness of man

- men playing men do not wear masks

- men playing women often do not wear masks but a white cloth (binan) wrapped around the head

- when a mask is used, it is for an exceptionally ugly woman

- (its ugliness is devoid of evil; just plainly unattractive

- gods are portrayed with exaggerated, joyous faces

- demon masks (buaku) are caricatures of the the nō-men (能面) ō-beshimi [also a demon mask]

- caricatures underscore the goodness of man by making the demons powerful looking on the surface, but cowardly/stupid as entities

- animals (in contrast) are created with a certain amount of realism

•Musical Components•

- Instruments involved: nô-kan flute, ko-tsuzumi (shoulder drum), o-tsuzumi (hip drum), and taiko drums (played with beaters).

- Vocals are heard in songs sung by a chorus of 6-10 men (called ji: 地–> ground/base), solos sung by actors, and the “kakegoe” of the drummers before or after they play (as well as the interjecting calls).

- “The notes of the flute, those of the singers the strokes on the drums and the calls of the musicians are… never improvised or predetermined… but are inserted in a pattern determined in advance” similar to the way Noh dances are constructed.

- Seven categories of patterns according to musical function

- Two kinds of patterns: Rhythmic (drums) and melodic (flautist, chorus and actor)

- The patterns have fluctuating character (placement/occurrence and duration) although not to the point of becoming unrecognizable.

- Whole musical patterns are learned and memorized (seen as the smallest unit in Noh music)

- “The taiko does not enter until the last section, in which it carries the rhythm to its greatest intensity and complexity.”

- Vocal interjections have a musical and psychological function

- Musically: guide the musicians by marking the beats of a rhythmic pattern.

- Psychologically: convey a direct emotional communication stronger than that which depends on activations of the intellect.

- “The pronunciation and the loudness of the calls vary according to the character and the dramatic power of the respective Noh”

•Performance And Dance•

- Female roles are played by men with masks.

- Voice, gestures and manner of dance are all determined by the form, age, gender, etc. Of the character that the performer appears as.

- An attempt to “capture the essence of the character… by means of a highly elaborate stylization” as opposed to one grounded in realism.

- Five major categories of Noh with their own variety of dance:

- Kami Noh

- Dignified and solemn plays in which the shite often appears as a lowly old man and returns in the second part as a God to perform a dance of felicitation. This category features gaku (dance taken from bugaku)

- Asura Noh

- “Warrior Noh” in which the shite performs as the spirit of a famous, usually defeated warrior (often from the Genji-heike wars) whose spirits must roam the battlefield eternally. This category features kakeri dance, in which the performer carries a sword or other weapon and re-enacts the moment of violence leading to his demise.

- Kazura Noh

- “Wig Noh” deal with female characters, the shite usually appearing as a village woman first then as a noblewoman in the 2nd part. These plays express feminine grace and elegance and are the central part

and focus of a programme. Over half the plays contain jo-no-mai, a quiet dance in

a slow tempo in which the movements are extremely restrained and refined.

- “Wig Noh” deal with female characters, the shite usually appearing as a village woman first then as a noblewoman in the 2nd part. These plays express feminine grace and elegance and are the central part

- Monogurui Noh

- “Lunatic Noh” is the miscellaneous category given the name because of the predominance of stories in which the cause of lunacy is the loss of a loved one. Dances are performed only if called for in text

- Kiri Noh

- “Ending Noh” feature the shite in the role of a supernatural or imaginary being (I.e: demon, monster, ghost, etc.). A Hataraki war dance is usually performed to display supernatural powers or to provide a vigorously entertaining dance appropriate for the end of a program.

- Noh dances are made up of set movement patterns, called kata (form—either in time or space).

- Each kata consists of kamae (position) and hakobi (progression/manner of walking which is often used by the audience to determine the overall skill of the performer).

- hakobi consists of sliding the whole foot forward and then lifting the foot in a straight line at an angle to the floor while maintaining heel contact. The whole foot is then lowered as a new step is taken.

- This results in a smooth, gliding-like effect but still projects an awareness of gravity.

- The basic standing position: tsune-no-mae

- Torso, held in one piece with no rotation, inclined slightly forward

- Back lengthened to achieve a straight line

- Knees slightly bent

- Arms curved downward and a little forward of the body

- Elbows lifted creating a fuller image and better line for the hanging sleeves of the costume.

- There are highly stylized and distilled kata that pantomime activities such as praying, holding a shield, or riding a horse. Many kata use the Noh fan called ogi. Some of these kata deal with ways of holding the fan, some create designs in space, and some are also pantomimic.

- Performers display both high energy but also a lack of tension/rigidity during performances, which requires great concentration and a freedom that comes from self-control

•宇高 竜成 (Udaka Tatsushige)•

Citations

WOLZ, CARL. “Dance in the Noh Theatre.” The World of Music 17, no. 3 (1975): 26-32.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43620004.

TAMBA, AKIRA. “The Music of the Noh.” The World of Music 17, no. 3 (1975): 3-12.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43620001.

Tyler, Royall. “Buddhism in Noh.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 14, no. 1 (1987): 19-52.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/30234528.

Presentation

Though we researched together and talked about our thoughts, we came away with different things; as such our presentation focuses on each of our experiences within the same scope.

Though we researched together and talked about our thoughts, we came away with different things; as such our presentation focuses on each of our experiences within the same scope.

See above materials.

B: Personally, as I experienced Noh several things really stood out to me: The concept of ichigo-ichie was one of them and manifested itself in various forms including the fact that no play is fully rehearsed, but everything comes together in one performative bout. I also really appreciated just how much care was taken in the treatment of props such as masks and saw it as both a practical and spiritual tradition.

D: From my reading it felt like Noh was treated as a history, rather than a living performance tradition. I also thought that way much of the theory described was not very helpful. The work is written in a style that seems to prioritize fact; so the concept of hana becomes important when talking about how Zeami created it; some more metaphor would have been helpful.

B: after seeing the actual performance, I think my appreciation of noh performers’ shear skill and versatility truly reached its maximum because I was actually able to witness it for myself. Little things like holding positions for long periods of time or moving in certain ways, I realized, made performing Noh exceptionally difficult in ways that would not be noticed off stage. I also had moments during which I felt as though the play stopped being simply a performance and I felt truly moved and like I was witnessing a spiritual ceremony taking place. Finally, I noticed the predominance of conflicts in Noh: they’re important because these Conflicts lead to the balance or imbalance of yin and yang and eventually produces something worth performing. This conflict is what makes Noh beautiful to me.

B: after seeing the actual performance, I think my appreciation of noh performers’ shear skill and versatility truly reached its maximum because I was actually able to witness it for myself. Little things like holding positions for long periods of time or moving in certain ways, I realized, made performing Noh exceptionally difficult in ways that would not be noticed off stage. I also had moments during which I felt as though the play stopped being simply a performance and I felt truly moved and like I was witnessing a spiritual ceremony taking place. Finally, I noticed the predominance of conflicts in Noh: they’re important because these Conflicts lead to the balance or imbalance of yin and yang and eventually produces something worth performing. This conflict is what makes Noh beautiful to me.

D: After watching the plays, and attending the lectures, I was struck by how deeply ingrained the concept of yin and yang is within the practice. Despite it being a theater of the “real,” where anything could go wrong at any moment and there is no best view, the plays are abstracted, idealized beauty. After actually watching some plays, I started to understand the aesthetic guidelines and philosophy a little more. In the second half of Haku Rakuten, a play that we saw, I even cried; the dance of the god Sumiyoshi was quite beautiful, and the music and calls of the chorus seemed to all come together perfectly, and even spiritually.

B: I saw my self splitting up different traditional practices into two categories in order to deal with this issue in my mind: on one hand you had practical traditions with very tangible and immediate results (treating masks with care and respect); on the other hand you had traditions who’s origins are less clear (seating arrangement on stage) or the purpose for which isn’t something “practical” per se (The hard to grasp classical Japanese used by performers).

B: I saw my self splitting up different traditional practices into two categories in order to deal with this issue in my mind: on one hand you had practical traditions with very tangible and immediate results (treating masks with care and respect); on the other hand you had traditions who’s origins are less clear (seating arrangement on stage) or the purpose for which isn’t something “practical” per se (The hard to grasp classical Japanese used by performers).

D: After all the research and experience, I thought that the “rigidity” with which Noh seemed to be associated, was more a system for the preservation of beauty. In presenting I said that: the history and tradition act as seeds, the musicians as dirt, the chorus as water, and the acting as sunlight; the combination of which produces this flower that is Noh.

B: I could not make a decision on if I wanted to change the less practical traditions and keep the practical ones in order to make Noh more accessible internationally and to a more modern audience, but I felt like it was an important dialogue that should be held between the audiences of Noh and the creative minds behind Noh in order to reach an acceptable and beautiful balance (thus ending one of Noh’s conflicts, the one it has with the modern audience member).

B: I could not make a decision on if I wanted to change the less practical traditions and keep the practical ones in order to make Noh more accessible internationally and to a more modern audience, but I felt like it was an important dialogue that should be held between the audiences of Noh and the creative minds behind Noh in order to reach an acceptable and beautiful balance (thus ending one of Noh’s conflicts, the one it has with the modern audience member).

D: I do not think anything about Noh should be changed. But education and workshop efforts, like those of Prof. Pellechia and Udaka-san, are important. Noh is much more enjoyable when you know what is happening.

We made our presentation in this style because, even though we were struck by different concepts and ideas, we both enjoyed Noh; we believe that many different people can enjoy Noh, for a variety of reasons.

We made our presentation in this style because, even though we were struck by different concepts and ideas, we both enjoyed Noh; we believe that many different people can enjoy Noh, for a variety of reasons.