Carl, Ayami, and I decided to spend our free morning today visiting Kiyomizudera Temple, a famous Buddhist temple and UNESCO World Heritage Site that is built up into the hillside. The temple offers beautiful, panoramic view of the city, and the view was all the more beautiful because there was still some snow on the trees.

We lit some incense at the main hall and then wandered through the gardens/grounds, which held a few different pagodas and shrines. The bright orange pagodas were especially striking against the snow, and they managed to stand out while also complementing and being complemented by the natural beauty all around.

Kiyomizudera also has a famous waterfall, with three separate streams of water that are said to bless people with longevity, school success, and romance. Visitors will catch the water in a ladle and drink from it, but we were a little wary of the fact that people were drinking straight out of the ladles, so we decided to skip that part.

Nevertheless, it was a still beautiful spot, surrounded on either side by big, old rocks covered with moss. As with the other temples and shrines that we’ve visited, the natural beauty, the architecture, and the religious meaning of the location combined to create a spiritually powerful atmosphere, even despite all of the tourists.

In the afternoon, we visited the studio of Tatsushige-san, a Shite Noh performer whose father is a Noh mask maker and performer. I thought that after our lecture from Diego and the four (?!?) hour Noh performance that we attended, I had a pretty good understanding of Noh, but I don’t think I’d really developed an appreciation of it until Tasushige-san’s demonstrations and presentation today.

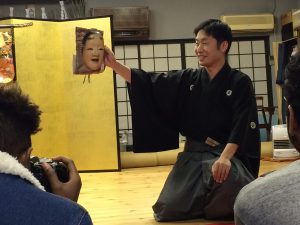

Tasushige-san showed us a lot of masks that his father had made, and he demonstrated how they can have different expressions depending on their angle. When he first brought out and held up the masks, I thought they looked a little alien and cold, but as he began to move them around on his hand, the expressions that had seemed distant and highly stylized suddenly came to life. The way in which he could animate the masks with a carefully angled flick of his wrist reminded me of the Buddhist eye-opening ceremony to bring spirit into statues. Indeed, there was an important spiritual aspect to the masks that I hadn’t been very aware of before today. As with tea ceremony, there is an emphasis placed upon appreciating and valuing objects, and Tasushige-san bowed to the mask before he put it on and before he wrapped it up and put it away again. He did it with such sincerity and simplicity that it seemed completely natural and proper.

Indeed, Tasushige-san emphasized that Noh masks are extremely special and important in Noh theater because by hiding the actor’s everyday identity, they allow him/her to project an identity that is beyond the limitations of any individual human identity. With masks, actors can become transformed into any character, male or female, deity or demon. When Tasushige-san was explaining this, he asked us to think about the masks that we wear everyday, literally but also metaphorically, and the ways in which we seek to represent ourselves in different ways. I recognized the similarities, but I was also aware of a key difference – wearing masks in Noh is a way to transcend oneself, rather than to cultivate an image and practice different forms of self-representation. In this way, Noh masks seems to be related to the fundamental goal of Zen Buddhism, namely to transcend one’s ego and the binaries created by a sense of self in order to get to the spiritual essence and truth of everything. A core aspect of Zen Buddhism’s approach to this goal is the belief that freedom can be found within and because of imposed limits and strictly rigorous practice, and I heard echoes of this in Tasushige-san’s words. In particular, the masks have tiny round holes for the eyes (the pupil part on the mask), which makes them extremely limiting to actors in terms of what they can see and, as a result, how much and in what ways they can move. I got the sense, however, that having such limited vision was one of the transformative elements of wearing a mask; by literally changing the way in which you see the world, the mask changes how you interact with it, and how you interact with the world then affects how you develop or experience a sense of self and an awareness of others. I would imagine that seeing fewer things at a time also makes the actor appreciate those things in new and more profound ways, freeing up his/her senses much in the way that people find freedom by the limitations of the ‘less is more’ aesthetic. At the same time, I can see how the mask also creates a level of distance between oneself and the world that would promote a level of detachment, which is another fundamental tenant of Buddhist teaching.

On a more literal and practical level, the masks also define Noh insofar as they provide very specific, technical limitations and parameters on the way in which actors move and behave on stage. A mask angled upward can look happy, while a mask angled downward could look sad, and even variations of a few degrees can cause a mask to go from looking neutral to sad or happy, so the actors have to be very careful to keep the mask’s expression consistent by maintaining a certain angle of their neck and spine as they are performing. Understanding this then suddenly helped me understand a lot of other aspects of Noh that seemed strange or very stylized – why the actors have to walk so slowly and in such a particular way, as if they’re gliding across stage, why the dancing is performed as a series of circular movements around the stage rather than more literal dance movements up and down, and why the stage assistants are always close at hand, placing props in the actors’ hands and supporting them as they move about the stage. Even the way the stage is set up – the fact that there are 4 pillars at each corner of the main stage – is related to masks. Actors wearing masks can’t see their feet, and the pillars help them determine where the edges of the stage are so that they don’t fall off (although Diego told us that this is something he has witnessed before).

I am very grateful to Tasushige-san for helping me understand the significance of Noh masks, which I now see as creating, representing, and bridging the many layers of Noh and its meanings. Noh masks make Noh theater the multifaceted, rich, and beautiful experience that it is, and understanding these masks has helped me understand and appreciate Noh as a form of art, tradition, a performance, and a spiritual experience.