***Final Presentation Found Below***

Pre-Departure Presentation

January 6th, 2016

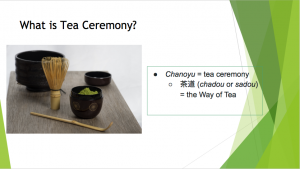

What is Tea Ceremony?

- The art of performing the preparation and serving ceremony of matcha (powdered green) tea.

- 茶道 (chadou or sadou) = the way of tea

- Can almost be thought of as a philosophy or way of living (Anderson 1)

- Jitsu = Practice

- Do = Philosophical meaning of tea

- Gaku = scholarly aspects

- Chanoyu = tea ceremony

- Chaji = formal version (Dougill, 125)

- About four hours long

- Consists of a meal, ‘thick tea,’ a break, and then ‘thin tea’ (lower quality)

- Chakai = informal version (Dougill, 125)

- About thirty minutes long

- Chaji = formal version (Dougill, 125)

Historical Background:

- Tea was introduced to Japan with Buddhism in the 9th century (Teforia)

- Chinese monks showed their appreciation and respect for tea by drinking it a formal manner, and Heian aristocrats adopted this tradition (Dougill 128)

- It began to lose popularity, however, and the practice of drinking tea was then reintroduced in 12th c. brought to Japan by monks who studied at Zen monasteries in China (Sen 11),

- Japanese monk Eisai brought tea seeds to Japan from China (Clancy 14)

- He initially promoted tea for its health benefits and its ability to keep the mind alert while meditating (Dougill 128)

- Japanese monk Eisai brought tea seeds to Japan from China (Clancy 14)

- Spread beyond monks to become a drink of the upper class (Clancy 15)

- Quickly turned into a lavish practice that involved ostentatious displays of wealth (Sen 11)

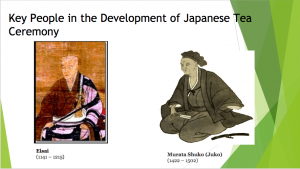

- Zen priest Murata Shuko (Juko) (1422 – 1502) redirected the focus of serving tea towards the spiritual aim of transcending the ego (Dougill 128)

- He served tea in small rooms and used simple, minimum, locally-made utensils, in contrast to the aristocrats’ way of serving tea, which emulated the large Chinese-style tea rooms and highly decorative utensils. (Sen 12)

- Designed the 4.5 tatami mat tea room at the Silver Pavilion, which served as the prototype for future tea rooms (Dougill 129)

- Reduced the number of utensils (Dougill 129)

- Added Zen calligraphy (Dougill 129)

- Often considered the founder of tea ceremony (Dougill 128)

- Takeno Jo-o (of the merchant class, many of whom were deeply involved in Zen) developed an aesthetic of Wabi tea

- Wabi is practiced in small, rustic huts with utensils of “quiet, humble character” (Sen 12)

- “Modest and without ostentation, [wabi] combines the aesthetics of Zen with the egalitarianism of democracy.” (Sen 12)

- Sen-no-Rikyu, Jo-o’s disciple, furthered this aesthetic (Sen 12) and developed a precise set of rules for tea preparation, codifying it into a unified and strictly regulated ceremony (Clancy 15)

- Extended Wabi aesthetic to Wabi-Sabi (Dougill 130)

- “Appreciation of the natural and simple, together with a feeling of melancholy at the transience of beauty.

- irregularity and understatement (vs showy and pretentious)

- Old and aged (vs new)

- Believed that in his tea house, all were equal, sitting together and sharing the same bowl of green tea (Clancy 15)

- A revolutionary idea given the strict class hierarchy in Japan at the time (Clancy 16)

- Powerful patrons (the daimyos Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi) → he became a powerful and an influential political figure (Clancy 16; Dougill 129)

- Tea at that time had a political function

- Used to settle disputes and solidify alliances (Dougill 129)

- Some, like Hideyoshi, who had a gold leaf tea room and gold tea utensils, still favored ostentatious shows of wealth in tea ceremony (Dougill 131)

- Tea at that time had a political function

- His descendents developed three separate schools of tea (Dougill 132)

- Omotosenke

- associated with aristocrats

- Mushanokoji

- associated with wabi aesthetic

- Urasenke

- Associated with common people

- More open to foreigners

- Today = 80% of tea ceremony practitioners are women

- Succession to the head, grand master position of schools is hereditary.

- Omotosenke

- Extended Wabi aesthetic to Wabi-Sabi (Dougill 130)

- 1587 = largest tea gathering in history, organized by Hideyoshi, with 800 pavilions open to the general public (Dougill 131)

- 1900s = “Feminization of tea” (Dougill 132)

- Studying tea became an important part of education for women

- One of the reasons that the majority of practitioners today are female, although they were originally all male

- “Internationalization [of tea ceremony]” has been driven by Urasenke School, which is represented in over 100 different countries and runs courses for foreigners (Dougill 132)

- There is even a series of ceremonies called Ryurei, pioneered by Sen Soshitsu XV (Daisosho) where the teishu (host) and guests sit on stools, as to appeal to foreign practitioners. (Ayami’s brain)

Cultural Information:

Connections to Religion:

- Influenced by Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism

- Zen Buddhism

- Tea ceremony’s goals of transcending ideas of self to accessing truth and unity are the same as the goals of Zen meditation

- Host is trying to unite with the guests (Dougill 127)

- “In Zen, truth is pursued through the discipline of meditation in order to realize enlightenment, while in tea we use training in the procedures to achieve the same end” (Sen no Rikyu, as cited by Dougill 127)

- Scroll hung in the tea room often has Zen quotation (Dougill 126)

- Flower arrangement is like what is found on an altar

- Incense like in a temple

- Concern with cleanliness (Dougill 130)

- Tea ceremony’s goals of transcending ideas of self to accessing truth and unity are the same as the goals of Zen meditation

- Taoism (Dougill, 126)

- Slowing down and getting in touch with The Way

- Facilitating energy flow through asymmetrical arrangements

- Bringing together the 5 elements

- Wood (charcoal)

- Metal (kettle)

- Earth (pottery)

- Fire (in hearth)

- Water (tea)

- Balance between giving (yin) and receiving (yang)

- Confucianism

- Places emphasis on tradition, etiquette, correct behavior, and regulated relationships between people

- Christianity? (Dougill, 127)

- Similarities to Catholic mass

- At the time tea ceremony was emerging, Christian missionaries were in Kyoto

- Zen Buddhism

Cultural Significance of Tea Ceremony:

- Personal meaning – for the host:

- Mental discipline (JNTO)

- Etiquette training (Dougill 124)

- A way to cultivate certain states of mind

- Peace of mind (Prideaux)

- The calm, content, and simplicity of wabi

- A form of mindfulness (Dougill 124)

- Zen practice (Dougill 124)

- Path to spiritual transcendence

- Strive to connect with the deep essence or inner nature of things

- “By repeating the same polished actions over and over again, fitting yourself into a pattern, you approach the core of yourself” (Sen Souoku, as cited in Dougill 127)

- Meaning for the guests:

- Tea room offering sanctuary or haven (Prideaux)

- A “respite” from the demands and concerns of the outside world and modern life (Clancy 17)

- A cultural tradition

- For Japanese, entering the tea room can be “a return to the heart of their culture, a journey back to their cultural identity” (Clancy 17)

- Ritual (Dougill 124)

- Performance of grace, discipline, and form (JNTO)

- “Social gathering” (Dougill 124)

- Bringing together host and guests

- “Shared communion” (Dougill 125)

- Bringing together host and guests

- Marking the seasons (Dougill 124)

- A celebration or special occasion

- Ichigo ichie = “Just this one meeting” or “This time only”

- Tea room offering sanctuary or haven (Prideaux)

- Rikyu (founder of modern schools of tea) identified the spirit of chadou in four basic principles: (Sen, 13)

- Harmony (和, Wa)

- Respect (敬 ,Kei)

- Purity (清 , Sei)

- Tranquility (寂, Jaku)

- These four rules underlie all the practical rules of tea and represent the highest ideals.

- They make the foundation for the philosophy of practicing tea ceremony.

- Principles of the way of tea are “directed toward all of one’s existence,” (Sen, 11)

- “In practice, the test lies in meeting each occurrence of each day with a clear mind, in a composed state.” (11)

- The manner of performing tea ceremony

- Intentionality / Deliberateness

- Sincerity

- Simplicity

- Precision

- Cleanliness

- Attention to detail

- The manner of performing tea ceremony

- The aesthetics of tea ceremony (especially the utensils) (Clancy 16)

- Wabi = “rustic beauty”

- Sabi = “elegant simplicity”

- Shibui = “understated tastefulness”

- Yugen = “vague mysteriousness”

- Aware = “a deep response to the passing of beauty”

- Miyabi = “refined sophistication”

- Shin-gyo-so = levels of formality; formal, semi-formal, informal

- Appealing to and stimulating the senses (Dougill 125)

- Sound = the quiet → more aware of sounds; murmur of boiling water, sounds like whispering wind because bits of iron are placed in the bottom of the kettle (Dougill 126)

- Taste = the bitter tea, the sweet confections

- Smell = the incense

- Sight = ceramics, hanging scroll, flower arrangement; sculpted ash in the hearth

- Touch = the warm ceramic bowl with the tea

- “In practice, the test lies in meeting each occurrence of each day with a clear mind, in a composed state.” (11)

Technical Information:

The Format of Tea Ceremony:

Preparations:

- Choosing a theme

- Often related to the time of year

- Reflected in the host’s outfit, the confections, the ceramics, the hanging scroll, the flower arrangement

The General Procedure:

- Guests (Okyakusan) seated in tea room in seiza style, with legs folded underneath them

- The Host (Teishu)

- Enters, kneels, bows, sits in front of kettle

- Takes a cloth from belt and folds it in a precise way

- Purifies the tea utensils and tea container symbolically

- Scoops powdered green tea into a bowl

- Uses a bamboo ladle to add hot water

- Whisks the tea

- Places the prepared bowl of tea on the floor for the first guest

Source: Japan National Tourism Organization http://www.jnto.go.jp/eng/indepth/cultural/experience/f.html

- First guest = guest with the most knowledge of tea ceremony (Dougill 125)

- Usually receives confectionaries to sweeten the palate before the bitter tea.

- Bows in thanks for the sweets and acknowledges their being the first to receive the confections, the second guest will tell or indicate them to go ahead. (This is repeated by the following guests)

- Bows in thanks for the tea and acknowledges their being the first to drink, the second guest will tell or indicate to them to go ahead. (This is all repeated by the following guests)

- Takes the bowl and holds it in a certain way (right hand around the bowl; left hand underneath)

- Raises it to the brow as a sign of respect

- Turns it clockwise two times, leaving the decorating facing away from him/her (only for Urasenke, this depends on the school)

- Examination, admiration, and discussion of the utensils and the wall-hanging (Dougill 125)

- Discussion of the utensils, wall hanging, and flower arrangement usually entail questions such as asking for the name of the piece, the artisan who crafted the piece, the make of the material, and why the teishu selected it.

Source: Japan National Tourism Organization http://www.jnto.go.jp/eng/indepth/cultural/experience/f.html

The Tea Garden:

Source: “Japanese Tea Ceremony” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_tea_ceremony#/media/File:Adachi_Museum_of_Art11s3.jpg

Source: “Japanese Tea Ceremony”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_tea_ceremony#/media/File:Tea_House_and_Roji_at_the_Adachi_Museum_of_Art.jpg

The Tea Room (Chashitsu):

- Parts of the room:

- Nijiri-guchi = small door

- Since guests must stoop to enter, they are forced to humble themselves

- Creates a sense that everyone is equal

- Tokonoma = alcove where a scroll is hung (Dougill 124)

- Nijiri-guchi = small door

- Design:

- Small room

- Generally, 4.5 tatami mats (Dougill, 124)

- Simple and rustic (Clancy 17)

- Thatched roof

- Unadorned clay walls

- Hearth or hanging kettle

- Simple flower arrangement

- Small room

Source: “Japanese Tea Ceremony”

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/32/e0/04/32e004ec3772578a60c46e5b042191cb.jpg

Source: Japan National Tourism Organization http://www.jnto.go.jp/eng/indepth/cultural/experience/f.html

The Utensils (Chaki, 茶器; more colloquially Odougu, お道具):

Chashaku (茶杓), a tea scoop, usually made of bamboo.

http://www.hibiki-an.com/product_info.php/products_id/355

Hishaku (杓), a ladle for hot and cold water, usually made of bamboo

http://www.nipponandco.com/blog/?p=360

Chawan (茶碗), the tea bowl, usually made through different types and styles of ceramics

http://www.hibiki-an.com/product_info.php/products_id/548

A different style of chawan

http://www.tablinstore.info/product/471

Chasen (茶筌), is the tea whisk, usually made of bamboo

https://samuraibuyer.jp/tw/item/detail.php?item_cd=honjien:10001159

Different styles of chasen

http://jpninfo.com/59920

Cha-ire (茶入), is the container in which matcha is put for the ceremony

http://cameronjcampbell.name/Tier2/Chadogu/Chaire/Chaire.htm#3

Cha-ire are generally put inside a silk bag until taken out during the ceremony.

Natsume (棗) is the cha-ire for usucha (light tea) powder

http://item.rakuten.co.jp/honjien/001-yo-kuromuji/

Chakin (茶巾) is the cloth that is moistened and used to symbolically purify the chawan.

http://global.rakuten.com/zh-cn/store/jubishi/item/550406/?s-id=borderless_recommend_item_zh-cn

Fukusa (帛紗) is the silk cloth which is used to symbolically purify most utensils and to pick up the hot lid of pots. A teishu carried one (1). The three pictures here are different colors, as men and women, as well as different schools, carry different colors.

http://global.rakuten.com/zh-cn/store/auc-houkouen-tea/item/sfu-0005/

A chawan, chasen, chashaku, and natsume with matcha placed inside to look like a mountain (as is traditionally done).

http://jpninfo.com/59920

Tea Ceremony Today:

- Somewhat of a dying art because of intensity of training, length of traditional ceremony, and inaccessibility

- Typically performed —-to mark seasonal changes and for special celebrations—

- A significant percent of Japan’s population has not experienced tea ceremony

- With Urasenke as the most open of schools, foreigners and tourists have multiple avenues through which to explore tea ceremony.

- Urasenke has schools around the world, including in the US.

- Urasenke also has a program in Kyoto called “Midori-kai” where foreigners intensely study tea ceremony for one year. It is not an easy program!

- Growing popularity of matcha, mainly for its health benefits

- We can see some of class issues that arise around tea ceremony

- It can be expensive to take lessons, depending on the teacher and location.

- If you purchase your own utensils, kimono, etc., the cost can increase exponentially.

- Certainly a legacy of the lavish, elite world of tea.

Background Information on Artisan Dairiku Amae:

http://www.totousha.com/dairik-amae/

- His main profession is architecture.

- His passion/interest is in the promotion of Japanese culture in daily life. He does this through:

- Coordinating programs, creating webpages, taking photos, and recording (in the archival sense)

- He calls this his “life’s work”

- He studies under the Urasenke school of tea (裏千家)

- He has been studying for six years (so nine years by now)

- He no longer goes to lessons regularly, but before he used to go every Sunday at 1pm – 5pm.

- He originally began taking tea lessons as an extension of his interest in traditional architecture.

- He thought that if he’d design tea houses, he should also know how tea houses are used

- Once he started practicing tea, he realized how important it was to his daily life

- He would come to lessons feeling stressed and worrying about different things, like exams, but once he began his lesson, he would focus so intently on performing the ceremony in an exact fashion that he would forget about his stress and worries.

- Rather he would feel and think, “Wow, I am just drinking tea right now.”

- And then later would feel his mind being “reset.”

- He currently lives in Totousha (the tea house) with two other individuals, living a life through tea. (as of 2014)

- In describing moments he has those “mind resets,” he says they happen in moments that are within the room performing, but more often than not, these moments of clarity come when he is in the mizuya (room you prepare everything in, usually adjacent to the tea room), sitting and preparing to move on to the next section of the ceremony. He describes a moment of tension that occurs right before going on — he wouldn’t go on and be like “let’s just wing it,” he creates this self-tension for the purpose of tea.

- He says he cannot count such moments of clarity because there have been that many!

- He finishes the interview by explaining how he wants to see tea in everyday life more casually and wants people without a tea background to be able to experience tea through him.

- He speaks of beauty and tea as opening the eyes. He says he could see beautiful things when he was younger, but he was not conscious of it.

A traditional tea ceremony.

Compare the traditional style to the “kagocha” style that Dairiku Amae uses:

There is an obvious difference, especially in how Dairiku Amae is trying to spread tea to anyone who is willing to try it. We plan to further explore this idea in the interview with him.

Interview Questions for Mr. Dairuku Amae:

Background:

- When did you first start studying tea ceremony?

- Where are you originally from?

- How did you become interested in it?/ Why did you decide to make tea your life’s focus?

- What was your training like? Do you still go to Urasenke lessons?

- Were there any moments of clarity or realization?

- Did you focus on anything specific during your training besides architecture?

- How often do you perform tea ceremony?

- Whom do you typically perform it for? Who/what sorts of people are your guests?

- For what reason/ occasion?

- In your 2014 interview with the Totousha website, you mentioned that you have “mind resets” in the mizuya most often, but also while practicing and performing. Can you describe for us what that’s like?

- How do they come to you?

- Is that the main focus of tea ceremony to you?

- How would you describe the place/ role of tea ceremony in Japan today? (

- Is it a necessary part of preserving past?

- Is it an important part of life today?

- Is tea ceremony still relevant?

- What do you think should be its place? (ie should it be more prominent, etc)

Personal:

- In our research, we found many writings mentioning the “feminization” of tea. Does gender matter in tea ceremony?

- What does tea ceremony mean to you?

- In our research, we found that Zen Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and possibly even Christianity were often referred to as being adjacent to, within, or even the core of tea ceremony. Would you agree with that?

- Do you consider tea ceremony spiritual or secular?

- Do you consider it as a part of national identity?

- In our research, we found that Zen Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and possibly even Christianity were often referred to as being adjacent to, within, or even the core of tea ceremony. Would you agree with that?

- Why do you do tea ceremony? What do you hope to achieve with tea ceremony?

- Do you do it for yourself or for your guests?

- While you have trained in the Urasenke school, you note that you are trying to make tea more accessible to others. One way you seem to do this is your “kagocha” series. How would you say that your (style of) tea ceremony compares to others? Do you identify with any particular school?

- Are there personal elements that you’ve added or aspects that you’ve modified? If so, why?

- In you 2014 interview, you mentioned that beauty was something that opens the yes, but also that one needs to consciously open their eyes to see beauty. Can you elaborate on this in the context of tea?

- How do you understand beauty/what does it mean to you? What makes something beautiful?

- How does tea ceremony affect the way that you live? Your day to day life and interactions with the world?

- Has tea ceremony affected how you think about yourself?

- What distinguishes tea ceremony from just making a cup of tea? Where is the line?

- Do you drink other types of tea (ie leaf tea)? Do you drink tea without tea ceremony?

Modernity and tradition:

- Do you think that there is an essential core of tea ceremony?

- To what extent is tea ceremony about/defined by the rules, rituals, and procedures?

- To what extent can you alter the rules, rituals, etc and still have it be tea ceremony? If you change it, does it lose its meaning?

- Do you consider your tea ceremony traditional?

- How do you relate to the past tea masters?

- Do you think tea ceremony does or can reflect modern life? Respond to it?

- Is there a modern tea ceremony/ it possible to have a modern tea ceremony?

- What does that mean to you?

- (How) do you respond to modern life with your tea ceremony?

- Is there a modern tea ceremony/ it possible to have a modern tea ceremony?

- How do you feel about all of the codified rules, rituals, and traditions of tea ceremony?

- Are they limiting? (vs Taoist idea of change)

- Can you still be creative?

- Do you feel inspired by them? Burdened?

- How much do you feel that you are able to move away from or alter those rituals and rules?

- Are you able to find a balance between tradition and innovation?

- Between tradition and individual/personal expression?

Spreading Tea Ceremony Internationally, Domestically

- What do you want your guests to understand or take away from your tea ceremony? What are you trying to convey?

- Does it vary depending on the guest? (Do you want tourists or westerners to take away something different?)

- How do you strike a balance between being subtle in what you convey and trying to make sure that people understand?

- How do you strike a balance between following your personal aesthetic/artistic sentiment and appealing to your guests?

- How do you take the identities of your guests into consideration? Do you perform tea ceremony differently for different types of guests (ie: Japanese, tourists, westerners)?

- What if guests don’t know what to do? What do you do? How much do you direct people/guide them through the process?

- Do you think about/worry about how tourists interpret tea ceremony?

- Given the global, euro-centric focus on the West, do you feel a responsibility/pressure to present/perform tea ceremony a certain way?

- How do you feel about the increasing popularity and trendiness of matcha tea internationally?

- Good? (press, etc)

- Or bad? (dilution of ceremony, out of context)

- Do you feel like you have to convey something about Japan to foreigners through tea ceremony? (ie responsibility to represent Japan given your unique background)

- Do you think traditional tea ceremony involves hierarchies/enforces power and privilege?

- (How) do you try to create equality with tea ceremony?

- How do you think about making tea ceremony accessible?

- Many of the things we’ve read about tea ceremony talk about tea rooms as sanctuaries or spaces that provide a respite from the concerns of daily life, and in your 2014 interview with the Totousha website, you mentioned that when you enter a tea room, your stresses fall away. That seems to be in tension with the kamocha and efforts to pull tea ceremony out of the constrained, elite, and traditional spaces of tea schools like Omotesenke and Urasenke. How do you reconcile or grapple with this tension?

- Do you think the the power or meaning of tea ceremony comes from the fact that it feels like an escape from life? Does bringing it out into the world and connecting it to life take away an essential aspect of its meaning and significance?

- Can it be connected to life and still be tea ceremony?

- If it becomes a part of daily life, does it lose its special (spiritual?) quality?

- Can it be connected to life and still be tea ceremony?

- Do you think the the power or meaning of tea ceremony comes from the fact that it feels like an escape from life? Does bringing it out into the world and connecting it to life take away an essential aspect of its meaning and significance?

Ultimately, we’d like to focus on the tension that seems to exist in Dairiku-san’s work between his desire to make the experience of tea accessible to those without a background in tea ceremony and his strong admiration of the “aha” or mind reset/clarity moments that seem to only come through a deep understanding of tea ceremony philosophy.

Works Consulted:

Anderson, Jennifer L. An Introduction to Japanese Tea Ritual. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991.

Ask This of Rikyu (Rikyu ni Tazuneyou), directed by Mitsutoshi Tanaka (2013; Tokyo: Toei Company, Ltd., 2014), Blu-Ray.

Clancy, Judith. Kyoto, City of Zen. Hong Kong: Tuttle Publishing, 2012

Dairiku, Amae. “Cha-no-yu Now: 天江大陸.” 陶々舎. March, 2014. http://www.totousha.com/dairik-amae/.

Dougill, John. Kyoto: A Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Japanese National Tourism Organization. “Tea Ceremony.” Cultural Quintessence. Last Modified 2000. http://www.jnto.go.jp/eng/indepth/cultural/experience/f.html.

Kato, Etsuko, ed. The Tea Ceremony and Women’s Empowerment in Modern Japan: Bodies re-presenting the past. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004.

Okakura, Kakuzo. The Book of Tea. New York: Duffield and Company, 1906.

Pitelka, Morgan, ed. Japanese Tea Culture: Art, history, and practice. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

Prideaux, Eric. “Tea to Soothe the Soul.” The Japan Times. May 26, 2002. http://www.pripix.com/features/tea.htm

Sen, Soshitsu XV. Tea Life, Tea Mind. New York and Tokyo: John Weatherhill, Inc., 1987.

Final Presentation (US Version)

We researched tea ceremony and then while we were in Japan, we had the opportunity to meet and interview a tea ceremony practitioner named Dairiku Amae

Our goal today is to share with you our experience interviewing and sharing tea with Amae-san and how our understanding of tea ceremony and of tradition and modernity changed as a result.

Rather than trying to offer a neatly packaged understanding of traditional tea ceremony or Mr. Amae, we are trying to explain our experience and how we perceived his work in making tea ceremony accessible and returning it to its roots.

Before coming to Kyoto, we researched tea ceremony, and Ayami studied tea at Urasenke in Hawai‘i.

Tea ceremony is the art of performing the preparation and serving ceremony of matcha (powdered green) tea. In Japanese, it is known as 茶道 (chadou or sadou) — the way of tea. It can almost be thought of as a philosophy or way of living (Anderson 1).

As a result, we understood tea ceremony as a rule oriented way of life.

A brief historical background on tea ceremony:

Tea was introduced to Japan with Buddhism in the 9th century (Teforia).

Chinese monks had a tradition of drinking tea in a formal manner, and this was adopted by Japanese aristocrats for a while, but it eventually lost popularity (Dougill 128). It wasn’t until the 12th century that the practice of tea drinking was reintroduced into Japan, this time by monks like Eisai, who studied at Zen monasteries in China (Sen 11). Eisai initially promoted tea for its health benefits and its ability to keep the mind alert while meditating (Dougill 128). But tea began spread beyond monks to become a drink of the upper class (Clancy 15), and it Quickly turned into a lavish practice that involved ostentatious displays of wealth, with large tearooms and highly decorative utensils (Sen 11).

Zen priest Murata Shuko (Juko) (1422 – 1502) redirected the focus of serving tea towards the spiritual aim of transcending the ego (Dougill 128). In contrast to the aristocrats, he served tea in small rooms and used a minimum number of simple, locally-made utensils (Sen 12). Juko designed the 4.5 tatami mat tea room, which served as the prototype for future tea rooms, added Zen calligraphy, and is often considered the founder of tea ceremony (Dougill 128-9).

Takeno Jo-o (of the merchant class, many of whom were deeply involved in Zen) developed an aesthetic of Wabi tea. Wabi is an asethetic focused around simplicity, modesty, and rustic, solitary beauty, so tea ceremonies based on that aesthetic were practiced in small, rustic huts with utensils of “quiet, humble character” (Sen 12).

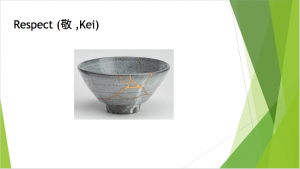

Sen-no-Rikyu, Jo-o’s disciple, furthered this wabi aesthetic (Sen 12) to Wabi-Sabi (Dougill 130). Wabi sabi is the appreciation of the natural and simple, together with a feeling of melancholy at the transience of beauty. It also recognizes irregularity and understatement (vs showy and pretentious) as well as the old and aged (vs new).

He also developed a precise set of rules for tea preparation, codifying it into a unified and strictly regulated ceremony (Clancy 15). Sen no Rikyu believed that in his tea house, all were equal, sitting together and sharing the same bowl of green tea (Clancy 15). Tea at that time had a political function, and Rikyu became a powerful and an influential political figure (Clancy 16; Dougill 129). He had powerful patrons like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Some, like Hideyoshi, who had a gold leaf tea room and gold tea utensils, still favored ostentatious shows of wealth in tea ceremony (Dougill 131).

Rikyu’s descendents developed three separate schools of tea (Dougill 132): Omotesenke, Mushanokoji, and Urasenke. Succession to the head, grand master position of schools is hereditary.

Rikyu (founder of modern schools of tea) identified the spirit of chadou in four basic principles: (Sen, 13)

- Harmony (和, Wa)

- Respect (敬 ,Kei)

- Purity (清 , Sei)

- Tranquility (寂, Jaku)

- These four rules underlie all the practical rules of tea and represent the highest ideals.

- They make the foundation for the philosophy of practicing tea ceremony.

Tea Ceremony is influenced by Zen Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Shinto(ism), and even Christianity.

- Zen Buddhism

- Host is trying to unite with the guests (Dougill 127)

- “In Zen, truth is pursued through the discipline of meditation in order to realize enlightenment, while in tea we use training in the procedures to achieve the same end” (Sen no Rikyu, as cited by Dougill 127)

- Scroll hung in the tea room often has Zen quotation (Dougill 126)

- Concern with cleanliness (Dougill 130)

- Tea ceremony’s goals of transcending ideas of self to accessing truth and unity are the same as the goals of Zen Buddihist meditation

- Taoism (Dougill, 126)

- Wood (charcoal)

- Metal (kettle)

- Earth (pottery)

- Fire (in hearth)

- Water (tea)

- Balance between giving (yin) and receiving (yang)

- Slowing down and getting in touch with The Way

- Facilitating energy flow through asymmetrical arrangements

- Bringing together the 5 elements

- Shinto(ism)

- Seasonal awareness, Awareness of and respect for nature and the environment, flower arranging

- Confucianism

- Places emphasis on tradition, etiquette, correct behavior, and regulated relationships between people

- Christianity? (Dougill, 127)

- Similarities to Catholic mass, esp with the use of a white cloth to wipe the tea bowl

- At the time tea ceremony was emerging, Christian missionaries were in Kyoto

Based on our research, we went into our trip with the sense that tea ceremony was very traditional and codified, with a lot of rules. We had expected that the tea ceremony we experienced would be traditional.

You can see these expectations in the basic questions we initially developed for Amae-san

- To what extent is tea ceremony defined by the many rules and rituals?

- Is it possible for tea ceremony to be modern?

- How much room is there for creativity and innovation?

We really wanted to focus on what we saw as a tension between Modernity and Tradition, as well as between innovating/creating and maintaining/preserving.

Background on Amae-san:

Born in Korea as the son of diplomats, he was raised in Hawai‘i, Syria, and Ukraine. He returned to Japan for college/university to study architecture. He began taking tea lessons because he wanted to design tea rooms, so he thought he should know the functionality of what he was going to design.

He is an architect by profession, but his passion (or “life’s work”) is the promotion of Japanese culture in daily life. His work is much less “traditional” than what one might imagine from a serious practitioner of tea ceremony. As powerful as tea ceremony can be, Amae-san believes is weak unless people can and want to participate in it, so his mission/goals are to make tea ceremony more relevant and connected to everyday life, so it’s accessible, enjoyable, and appealing to people.

He wants to surprise and entertain guests, and because of this, he is very playful with tea ceremony. For example, he has done a collaboration with the company Muji, where he performed tea ceremony in their store using only products he found in the location.

What our experience was on the day!

We started the day by collecting spring water from Shimo-Goryo Shrine.

Dragging water makes you slow down and in turn appreciate surroundings.

Feeling the weight of the water connects you physically to the water in a way that makes you all the more appreciative of how much of a scarce resource it is.

We then went to pick up wagashi, or traditional Japanese confections. Amae-san gets sweets from same person every time, and there’s a definite personal connection!

After we arrived at Amae-san’s house, Totousha, we worked on cleaning the room. Louisa sweeped the entire room, and then our whole group wiped down the floors, first with wet rags and then with dry rags. This act made us more aware and appreciative of the room, as well as of the minute details that made the space so beautiful: the light coming through the window, the scent of the tatami mat, the cleanliness of the space made us feel the beauty of the room.

Then Amae-san made us tea. As he did so, he told us about role of host and also demonstrated how host is mindful, aware and thoughtful, and watching the graceful, purposeful movements that he made was almost like watching a dance.

He created an experience with lots of different components that appealed to different senses (incense, flowers, tea, sweets, sound of gong, etc), to draw in many people and help them experience the power of tea. This really worked b/c most of us had very powerful and uniquely personal experiences. For example, personally, drinking my bowl of matcha, I (Louisa) felt transported, at peace, aware of and appreciative of everything around me. The way he’d served tea had seemed very casual, but I realized that he had actually accomplished something powerful.

Sharing what we learned!

Amae-san made us think about how we were defining modernity and tradition when he told us that he doesn’t want to think in terms of modernity and tradition. For example, he likes to imagine Rikyu was born yesterday and he like to think back to time before schools, when tea ceremony practitioners just did what felt right. Thus, what we think of as Amae-san’s ‘modern’ tea ceremony (art installation, no talking, sauna tea, no seiza, go to the public bathhouse) might actually be more ‘traditional’/true to the essence of the tradition (even though it looks less traditional) and thereby returning tea to the roots of the tradition. He is stripping away the pretension and rituals and codification to get back to the basics of the philosophy

He is not necessarily changing the fundamental essence of tradition but, rather, translating it. What he does may look and sound very different than traditional forms, but the meaning is the same.

Tradition and innovation aren’t necessarily opposed. It’s possible to be at the forefront of culture while also being traditional in certain ways. Amae-san is taking the philosophy of tea ceremony and extending it, applying it in new ways and contexts. He is taking Zen philosophy of stripping things down to their essential nature and applying it to tea ceremony itself. It is almost as though he is asking, “who/what is tea ceremony? What is its essence?”

For example, Amae-san work to have people leave knowledge at the door — an act that is about humbling people. In older times, power used to come from swords, and everyone leaving their sword at door was a way of humbling and equalizing everyone in the tea room, a concept that comes from Rikyu. Today, power and privilege are tied to knowledge, and to humble people, Amae-san designs his tea ceremonies so that knowledge of tea ceremony is not essential or even helpful (challenging expectations of older, knowledgeable people).

By focusing less on rules and rituals, his whole approach embodies and extends idea of Ichigo ichie which roughly means “a once in a lifetime experience” – the idea that tea ceremony should represent a unique coming together of components. He argues that having so many rituals/rules can take away from ichigo ichie because people feel like they know what to expect. With Amae-san’s tea ceremony, everything different each time, which encourages mindfulness and awareness and appreciation. Ultimately, you’d expect that the avant garde would be inaccessible, but what’s so powerful and interesting about what Amae-san is doing is that it’s at once avant garde/innovative and accessible.

However, we were still a little confused and decided to return to the idea of the four basic tea principles. We saw and learned about the 4 basic principles of tea ceremony through and in Amae-san’s work, thus experiencing their power.

At Amae-san’s tea room, we saw harmony between people, utensils, elements and environment. He works to make harmony between the sweets and the season (yukimochi = snow mochi). The softly falling snow outside created a calming sense, as the sweet snow confection blended beautifully with the matcha tea.

When cleaning the house, we not only felt respect for the place and objects we were cleaning but also respect for each other as well as ourselves. It was truly for each other and the inner spirit within us that we were cleaning.

In terms of purity, he had a very simple tea ceremony. He also taught us that silence is also sound and absence can be beauty. Because his tea ceremony is about removing unnecessary rituals, rules, or embellishments, he is able to use tea ceremony to restore freshness or purity to the mind.

Tranquility comes from the setting. Amae-san works to bring people together, making people comfortable by serving tea. He is bringing elements together, bringing senses together, bringing people together from different backgrounds.

Ultimately, all of these principles come together and interact, creating a beautiful tea ceremony.

In terms of some of the lessons that we’re taking back with us and want to share with you today…

As Williams students, we tend to over-intellectualize and over-analyze, but it’s important to realize that we can’t or shouldn’t just try to fit things into one box. There is not a simple binary of tradition or modernity, or perhaps not even a spectrum. As Zen Buddhism teaches us, things can and do hold contradictions.

Ultimately, tea is not just a drink and tea ceremony is not just a tradition It’s an experience, a state of mind, an attitude, a way of living that originated as a way of bringing people together and providing sanctuary/beauty during troubled times.

Amae-san very much embodied this for us. For him, it’s not about the rules; it’s about how he lives, how he thinks, and interacts with people. As students, very important for us to remember what Amae-san taught us – that it’s ultimately not about who knows more or who does things the right way. Tea, like life, is about human interaction, about balancing giving and receiving, and about learning from and appreciating the people, objects, and environment around us.

We chose this photo because it shows our simple understanding of tea ceremony growing into a more complex one, and then our view of tea ceremony as something so complex and ritualized as being returned to the simple essence of its philosophical roots.