Volume 2 – Number 1 – April 2016

Welcome

Upcoming Events

Faculty On Leave

New Faces in History

An Interview with Annie Valk

Graduate School Admissions and Graduate School Advisor

New Courses in History for 2016-2017

The Department’s Junior and Senior Advisory Groups

What They are Publishing – News from Faculty

Our History Students Abroad

History at Mystic

Dear Clio

In the Chapin Corner

Internships for History Majors

Careers for Historians

Welcome

H. L. Mencken may have nastily quipped that a historian was “an unsuccessful novelist,” but we historians often like to think of ourselves as more substantive than journalists (Mencken’s profession), and so we are very pleased to publish our second annual Newsletter. News features, helpful information, insight into historians’ minds, even a little entertainment: we’ve got it all.

H. L. Mencken may have nastily quipped that a historian was “an unsuccessful novelist,” but we historians often like to think of ourselves as more substantive than journalists (Mencken’s profession), and so we are very pleased to publish our second annual Newsletter. News features, helpful information, insight into historians’ minds, even a little entertainment: we’ve got it all.

We are deeply grateful for the tireless work of Professor Chris Waters, the History Department’s Student Liaison, who has written and gathered material for this issue and cheerfully reminded his colleagues to submit the rest. We also depend on Linda Saharczewski, our Administrative Assistant, for all her digital prowess in producing the Newsletter. If you have any ideas or materials you would like to see included in next year’s issue, please send them to Professor Waters ([email protected]).

Enjoy!

Karen Merill

Chair, Department of History

Frederick Rudolph Professor of American Culture

Upcoming Events

DEPARTMENT RECEPTION – Tue, Apr 26, 7:00-8:00 pm, Dodd House living room

History Department reception for all majors, potential majors, and students interested in History. Pizza and refreshments provided. Come and meet members of the History faculty and other History students, and learn about courses for next year.

THESIS COLLOQUIUM – Wed, May 4 – 6:30 – 9:45 pm, Faculty Club

Come to hear Cleo Nevakivi-Callanan, Phoebe Hall, Arnold Capute and Joshua Morrison discuss and defend their senior theses this year – especially valuable for juniors contemplating writing a thesis next year.

The full schedule of presentations is available from this year’s thesis program director, Professor Alexandra Garbarini: [email protected].

DEPARTMENT BBQ – Tue, May 17, 5:30-7:30 pm, Hollander Courtyard

Annual History Department Spring BBQ. All welcome!

RECEPTION FOR GRADUATING SENIORS – Sat, June 4, 10:30 am, Stetson Reading Room

Annual reception for graduating seniors and their families and friends.

Faculty On Leave

The following members of the Department of History will be on leave for all or part of the 2016-17 academic year:

Leslie Brown – Fall

Jessica Chapman – Fall

Aparna Kapadia – Fall/Spring

Eric Knibbs – Fall

Gretchen Long – Fall/Spring

Shanti Singham – Fall/Spring

Carmen Whalen – Fall

K. Scott Wong – Fall/Spring

New Faces in History

Alexander Bevilacqua will be joining the Department as a new assistant professor of history in the Fall of 2017, appointed to teach all aspects of early modern European history (c.1450-1789). Appointed after members of the Department conducted an extensive international search last Fall and during Winter Study, ably assisted by student members of the Department’s advisory groups, Alex will be completing his final year as a postdoctoral member of Harvard’s Society of Fellows next year before formally joining the Williams faculty. An undergraduate at Harvard College, recipient of an MPhil in Political Thought and Intellectual History from Cambridge University, and recent recipient of his PhD in History from Princeton University, Alex is a cultural and intellectual historian of early modern Europe, focusing in particular on the productive exchanges between European and Arab scholars in the early modern world. He is especially interested in the dissemination of the world of Arab learning in Europe and has written, amongst other things, on European translations of the Qu’ran in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He is currently completing two books, The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment (for Harvard University Press), and a co-edited collection of interviews with intellectual historians, Intellectual History in Practice (for the University of Chicago Press).

Anne Valk, Associate Director for Public Humanities at Williams, joins the Department  as a Lecturer in History this semester. Annie is a specialist in oral history, public history, and the social history of the United States in the twentieth century. She received a BA in psychology from Mount Holyoke College in 1986 and a PhD in history from Duke University in 1996. She has published two books in US women’s history, including Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Feminism and Black Liberation in Washington, D.C. (University of Illinois Press, 2008), which won the Richard Wentworth Prize for the best book in US history published by the University of Illinois Press, and Living with Jim Crow: African American and Memories of the Segregated South (Palgrave, 2010), a collection of oral history interviews co-edited with Professor Leslie Brown and recipient of the annual book prize awarded by the Oral History Association. Before coming to Williams in 2014, Annie was Associate Professor of History and Director of Women’s Studies at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville (1996-2007) and Deputy Director of the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage at Brown University (2007-2014). At Williams she serves as Associate Director for Public Humanities, a position shared by the Davis Center and the Center for Learning in Action. She teaches experiential and community-based classes in oral history and public history and this semester is offering HIST 371, “Oral History: Theory, Methods, Practice”. She is the current President of the Oral History Association (2015-16) and a series editor of “Humanities and Public Life,” a new book series published by the University of Iowa Press.

as a Lecturer in History this semester. Annie is a specialist in oral history, public history, and the social history of the United States in the twentieth century. She received a BA in psychology from Mount Holyoke College in 1986 and a PhD in history from Duke University in 1996. She has published two books in US women’s history, including Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Feminism and Black Liberation in Washington, D.C. (University of Illinois Press, 2008), which won the Richard Wentworth Prize for the best book in US history published by the University of Illinois Press, and Living with Jim Crow: African American and Memories of the Segregated South (Palgrave, 2010), a collection of oral history interviews co-edited with Professor Leslie Brown and recipient of the annual book prize awarded by the Oral History Association. Before coming to Williams in 2014, Annie was Associate Professor of History and Director of Women’s Studies at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville (1996-2007) and Deputy Director of the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage at Brown University (2007-2014). At Williams she serves as Associate Director for Public Humanities, a position shared by the Davis Center and the Center for Learning in Action. She teaches experiential and community-based classes in oral history and public history and this semester is offering HIST 371, “Oral History: Theory, Methods, Practice”. She is the current President of the Oral History Association (2015-16) and a series editor of “Humanities and Public Life,” a new book series published by the University of Iowa Press.

An Interview with Annie Valk

Below is an excerpt from a conversation between Karen Merrill and Annie about oral history.

What got you first interested in oral history?

I didn’t know anything about oral history when I started graduate school. It turned out, however, that Duke University, where I was a student, had just received a large grant to start an oral history project focused on the experiences of African American southerners during the period of segregation. As a graduate student in American history, I needed a job and that new project was looking for someone to help coordinate it. I ended up doing that for five years and it completely changed how I thought about my work as a historian. Hearing people recall their past experiences and reflect on the past made me appreciate history as something that lives in people’s memories and in the collective memory of communities…. I should say, too, that the Duke project ended up collecting about 1,300 interviews – it’s an impressive collection (called “Behind the Veil: Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South”). But I also learned that no project needs to be that big!

What is oral history exactly? Is it a method? A way of making just another source base, like written, documentary evidence? Are there rules for doing it?

People use the term “oral history” to refer to both a process or method and the interview that is the outcome of that method. Oral history is a great way to produce historical sources, especially documenting experiences and events that might otherwise go unrecorded. Oral historians talk about “doing history from the bottom up,” in other words, using interviews to preserve the voices of people whose experiences might not show up in archives or the documentary record. Lots of oral historians, for example, are interested in African-American history, labor history, women’s history, and topics from social history like domestic life or community change. Now, lots of people are using oral history to create multimedia projects: documentary films, of course, and also audio cell phone tours, mobile apps, exhibits in museums and online, and lots of other creative ways to share stories and revelations from oral history interviews. I’m really excited to develop some projects like these with Williams’ students in the class I’m now teaching in the History Department.

There aren’t “rules” per se, but the Oral History Association in the United States has developed a series of best practices for doing oral history. Those practices include guidelines for the best way to conduct and preserve interviews, and standards for ethical practices to make sure that people understand what they can expect for their interview and what will be done with the interview after it is complete.

It seems that oral history really is only applicable for modern historical research, because you can’t go back to folks, say, in the Middle Ages and ask them what they remember about what happened 20 years before. But is that true, that it can only be used for modern history topics?

Well, that’s a really interesting question. It isn’t possible to do oral history with people who are no longer alive – although oral historians joke about using séances to contact the dead! It turns out, however, that if you look at the kinds of sources that are available for studying earlier historical periods, many of those sources started out as oral and were written down later. That includes things like newspaper and journalistic accounts, police records and court depositions, folklore, and stories that get passed from one generation to the next.

What’s been the best and worst oral history you’ve ever done? Why?

Well, every interview I’ve done has been different and it is like comparing apples to oranges to elephants to rate them! My worst interview was probably my first one, with a woman who’d been part of the Black Panther Party chapter in D.C. I was so excited to do it and had planned for weeks, doing background research and getting ready. The interview went great and I learned a lot from her. After finishing it, I walked out to my car and did what you are never supposed to do, I popped the cassette tape (obviously this was before the turn to digital recordings) into my car tape player and hit play. There was no sound! I realized I had conducted the entire interview with the pause button on and never recorded anything! I was so mad and embarrassed but I knew I had to salvage something from the interview or else I would have wasted my narrator’s time. So I sat in my car and jotted down as many notes from my memory about what we had talked about. I then wrote them up and sent them to the person I had interviewed and got her to review them for accuracy as well. Obviously I never had any direct quotations from that interview but I was able to figure out a way to still use what I had learned. And, I never made that mistake again!

As President of the Oral History Association, will you get to make a speech at the annual conference?! If so, what will it be on?

No, no speech at the association’s meeting. It will be a very busy conference – it’s in October – and I will have many responsibilities and, I hope, a lot of fun. I will be giving a paper as part of a session at that conference, though. That paper, which I haven’t written yet, will be thinking about the roots of oral history in consciousness raising, a technique that got popular as part of the women’s movement in the 1960s and 1970s.

Graduate School Admissions and Graduate School Advisor

For those students thinking about possibly pursuing a graduate degree in History or related For those students thinking about possibly pursuing a graduate degree in History or related fields, the Department of History now has a Graduate School Advisor. Obviously, all members of the Department have experience of graduate school and would be happy to talk with students about their experience. But for those interested in preliminary discussions about possible options, one of the most useful things to do might be to set up a time to meet with the Graduate School Advisor, who is customarily the member of the Department who also heads the program for seniors writing theses – this year and next Professor Alexandra Garbarini ([email protected]).

If you will be continuing on in the world of higher education (law school, graduate school in history or other fields, etc) do let us know so we can include you in future editions of the newsletter.

Several graduating seniors and recent Williams graduates in History will be starting graduate programs in the Fall, including the following individuals:

Ahmad Greene-Hayes ’16 – Princeton University – PhD in Religion (also recipient of a Watson Fellowship)

Sara Kang ’14 – Harvard University – MA in Regional Studies (East Asia)

Joseph Leidy ’13 – Brown University – PhD in History (currently completing an MA in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas, Austin)

Joshua Morrison ’16 – University of Virginia – PhD History (19th century US) (also the recipient of the Scott Graduate Study Prize in History

New Courses in History for 2016-2017

The list of courses being offered by the History Department next year – almost seventy of them in all – is now available on-line in the course catalog. The Department is offering a number of new courses next year, along with several that are substantially revised. Descriptions can be found by clicking on the links below: The Department is offering a number of new courses in the Fall. Descriptions can be found by clicking on the course title below:

First-Year Seminars and Tutorials:

HIST 165(S) The Age of McCarthy: American Life in the Shadow of the Cold War (Chapman)

Introductory Survey Courses:

HIST 210(S) The Challenge of Isis (Bernhardsson and David Edwards)

Advanced Electives:

HIST 387(S) Living With the Bomb (Chapman and James Nolan)

Advanced Seminars and Tutorials:

HIST 402(S) A History of Family in Africa (Mutongi)

HIST 413T(S) History of Taiwan (Reinhardt)

HIST 479(F) Recent U.S. History: The 1970s and 1980s (Dubow)

The Department’s Junior and Senior Advisory Groups

The Junior and Senior Advisory Groups (JAG and SAG) play a major role in the life of the Department, advising the chair and other members of the Department on such matters as the History curriculum, the structure of the major, advising within the major, and public events, both social and intellectual. In years when the Department is hiring new professors, the members of SAG and JAG participate in the hiring process, meeting with the candidates and evaluating them from the perspective of students and History majors. This year members of the advisory groups played an especially important role in Department’s hiring of a new historian of early modern Europe.

Do you have ideas about the major or the Department and its undertakings? Are there things we should be doing, or should do differently? Reach out and share your ideas with members of the advisory groups, who are listed below! Better still, apply to join an advisory group. At the beginning of each academic year a call is sent out for self-nominations for new junior History majors who would like to be considered for the Junior Advisory Group. Watch this space, or contact the Department chair early in September!

Senior Advisory Group

Jochebed Bogunjoko [email protected]

Adrianna DeGazon [email protected]

Maxwell Dietrich [email protected]

Ahmad Greene-Hayes [email protected]

Phoebe Hall [email protected]

Lisa Li [email protected]

Kristian Viggo Hoff Lunke [email protected]

Josh Morrison [email protected]

Katherine Pollan [email protected]

Junior Advisory Group

Aglaia Ho [email protected]

Ricardo Diaz [email protected]

Lily Lee [email protected]

Jackson Myers [email protected]

Rachel Schwartz [email protected]

Marisol Sierra [email protected]

Ellie Wachtel [email protected]

Evan Wahl [email protected]

Jocelyn Wexler [email protected]

What They are Publishing – News from Faculty

When members of the Department of History are not teaching or engaged with committee work in the Department and at Williams more generally (or writing letters of recommendation!), they are productive in their scholarly fields. In addition to serving on numerous professional bodies, reading various grant and manuscript proposals, writing book reviews, serving as consultants, and presenting papers at scholarly conferences, amongst other professional tasks, they are busy with their own scholarship. In our last newsletter we showcased several books recently published by members of the Department. Below are some of the recent articles on which Williams historians have been hard at work.

Magnus Bernhardsson has written an article that is shortly to appear in the Proceedings of the British Academy, “Gertrude Bell and the Antiquities Law in Iraq.”

Jessica Chapman has written a lengthy research guide, “Origins of the Vietnam War,” that will soon appear in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History.

Alexandra Garbarini was recently the co-editor (with Boris Adjemian) of “Victim Testimony and Understanding Mass Violence,” a special issue of Etudes Arméniennes Contemporaines 5 (June 2015), for which she also wrote an article, “Document Volumes and the Status of Victim Testimony in the Era of the First World War and Its Aftermath.”

Roger Kittleson has written “Fausto dos Santos: The Wonders and Challenges of Blackness in Brazil’s ‘Mulatto Football,’” an article that is about to appear in Football and the Boundaries of History: Critical Studies in Soccer, edited by Brenda Elsey and Stanislao Pugliese (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). His book, The Country of Football: Soccer and the Making of Modern Brazil (University of California Press, 2014) was recently awarded the Warren Dean Memorial Prize for the best work on Brazil published in English in 2014.

Gretchen Long has an article about to appear in a special issue of Southern Quarterly focusing on medicine in the American South, “Conjuring a Cure: Folk Healing and Modern Medicine in the Fiction of Charles Chesnutt.”

Annie Reinhardt has recently published three new articles: “Treaty Ports as Shipping Infrastructure,” in Law, Land, and Power: Treaty Ports in Modern China, edited by Robert Bickers and Isabella Jackson (Routledge, 2016); “Lu Zuofu and the Teaboy: The Impact of the Minsheng Company’s Management Practices on Yangzi River Shipping Companies, 1930-1937,” Guojia hanghai 12 (August 2015); and “Locality and Opportunity in the Minsheng Industrial Company: Lu Zuofu, 1925-1937,” in Difang zhi jindaishi: Zhou xian sheshi de sixiang yu shenghuo [The Modern History of Localities: The Thought and Life of Elites at the Prefectural and County Levels] (Jindaishi yanjiu [Modern History], publisher, 2015).

Chris Waters published an article, “Wilde in the ‘Fifties,” in Sex, Knowledge and Receptions of the Past, edited by Kate Fisher and Rebecca Langlands (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Our History Students Abroad

Edinburgh Reflections, by Jackson Myers ‘17

Edinburgh Reflections, by Jackson Myers ‘17

It seems to me that in the discipline of history we, or at least I, have perpetually underestimated the importance of geography on the course of history. That changed for me in March when I visited Edinburgh. My hostel was right at the base of Edinburgh Castle, a stark outcropping of volcanic basalt rising 100 feet into the air, first fortified in pre-Roman times. The castle is but the first indication of Edinburgh’s deep connection with its geography. As I walked down the narrow and surprisingly steep closes between the tourist kilt and whisky shops of the Royal Mile, into the valley separating the Old and New Towns, I found myself grappling with the hills the same way the city’s builders did. Arthur’s Seat, a mountain towering over the city with a power and magnificence befitting its royal namesake on the opposite end of the Old Town from the castle, is the coup de grace. It is a remnant of the same prehistoric volcano which birthed Castle Rock, and, while not an easy stroll, the 250 meter climb to the summit was in every sense of the word worthwhile. Splayed out from the base of the mountain is the crowded Old Town, precipitously placed on its ridge-like hill and utterly dominated by the Castle at its west end. Looking north is the New Town, product of the Georgian era and much flatter and statelier than the occasionally Gothic Old Town, until it reaches the Firth of Forth, the economic hub of Lothian. Starting with the castle and moving all the way to Arthur’s Seat, Edinburgh is a city which bears the imprint of the earth underneath it; it is quite literally built around its geography. The history of Edinburgh, and of Scotland as a whole, is deeply intertwined with terrain and the Earth, but Scotland is not an exception – her tie with geography is only more obvious from her incredible crags and highlands. Places like Edinburgh, and Scotland as a whole, remind us that geography is not just a helpful corollary to the study of history – it is its beginning and, perhaps, its most efficacious driver. Sometimes it just takes climbing a mountain to remember that.

(Jackson Myers is a junior majoring in History and Classics, currently a member of the Williams-Exeter Programme at Oxford University)

Studying in Edinburgh, by Jocelyn Wexler ‘17

Studying in Edinburgh, by Jocelyn Wexler ‘17

Studying history in Scotland at the University of Edinburgh was very different from studying history at Williams. At the University of Edinburgh, I took a history class entitled “Modern Scottish History.” This class met three times a week for fifty minutes. Two of our weekly classes were taught in a large lecture hall with over fifty people in attendance. There were two lecturers who switched off. Once a week, we met in tutorial groups. These tutorial groups consisted of roughly twelve students and one tutor. During our tutorial, we discussed a pre-assigned question based on a weekly reading assignment. During the semester, we wrote two short papers that were graded anonymously by the tutors. At the end of the semester, there was one cumulative exam. While I really enjoyed my history class at the University of Edinburgh and felt that I learned a lot, I also missed the more interactive style of the Williams History Department.

(Jocelyn Wexler is a junior majoring in History who spent last Fall studying at the University of Edinburgh)

History at Mystic

The Williams-Mystic Maritime Studies Program was created by Williams History Professor, Benjamin W. Labaree, in 1977. He developed the program because there were few locations in the country where a history major could be as immersed in an historical setting as at Mystic Seaport, which is both the program’s campus and the largest maritime museum in the United States. Here one can experience the past by strolling the streets of our historic village, climbing aloft on the world’s only existing wooden whale ship, learning to sail traditional watercraft, or shaping red hot metal at our blacksmith shop. The history course, “Americans and the Maritime Environment,” is also designed to take advantage of the million objects in the museum’s collection, as well as the vast holdings of the G. W. Blunt White Library, one of the world’s finest maritime history collections. Among its many thousands of books and periodicals the library also houses a large oral history collection, over a million historic photographs, and another million pieces of manuscript like ship’s logs or letters from voyaging captain’s wives. Williams-Mystic’s interdisciplinary focus also means our study of the past becomes the foundation upon which the semester’s literature, marine science, and marine policy courses are based.

The Williams-Mystic Maritime Studies Program was created by Williams History Professor, Benjamin W. Labaree, in 1977. He developed the program because there were few locations in the country where a history major could be as immersed in an historical setting as at Mystic Seaport, which is both the program’s campus and the largest maritime museum in the United States. Here one can experience the past by strolling the streets of our historic village, climbing aloft on the world’s only existing wooden whale ship, learning to sail traditional watercraft, or shaping red hot metal at our blacksmith shop. The history course, “Americans and the Maritime Environment,” is also designed to take advantage of the million objects in the museum’s collection, as well as the vast holdings of the G. W. Blunt White Library, one of the world’s finest maritime history collections. Among its many thousands of books and periodicals the library also houses a large oral history collection, over a million historic photographs, and another million pieces of manuscript like ship’s logs or letters from voyaging captain’s wives. Williams-Mystic’s interdisciplinary focus also means our study of the past becomes the foundation upon which the semester’s literature, marine science, and marine policy courses are based.

The study of history and our other disciplines isn’t just carried out along the Connecticut shore; faculty and students also travel together on three extended field seminars. Since the days of Dr. Labaree we have felt that to study the sea one must experience it, thus a ten day offshore cruise on a sailing ship. We also spend a week traveling the Pacific Coast Highway, and four days among the swamps and salt marshes of southern Louisiana in order to compare those environments with that of our New England home.

Glenn S. Gordinier

Faculty Chair, Williams-Mystic

For further information, visit: http://mystic.williams.edu/

Dear Clio

The Department of History is proud to continue its regular column in the newsletter, “Dear Clio.” Clio, the Muse of History, will be very happy to answer all of your questions.

If you have a question that you would like addressed, please send it either to the editor of the newsletter (Chris Waters) or to Clio herself, at [email protected]. The answer to your questions will appear in the next edition of the Department’s newsletter.

Dear Clio,

What sort of cake did Marie Antoinette have in mind when she supposedly said “Let them eat cake!”?

She had in mind a brioche, the croissant’s lesser cousin. The French makes this very clear. Or rather, she did not, for there is no evidence that Marie ever thought to mitigate the hunger of the French peasantry via breakfast rolls. The Brioche Proposal first occurs in the autobiographical Confessions of Rousseau, who ascribes it to an unspecified “grande princesse.” Because everyone’s favorite Enlightenment philosopher wrote twenty-six years before Marie lost her head, and a good several before she ever arrived at Versailles to look down her nose at the rabble, it seems unlikely that she can have inspired Rousseau’s quotation. Abraham Lincoln once observed that “The trouble with quotes on the internet is that you can never know if they are genuine,” and it would seem that his wisdom extends to eighteenth-century print media as well.

to mitigate the hunger of the French peasantry via breakfast rolls. The Brioche Proposal first occurs in the autobiographical Confessions of Rousseau, who ascribes it to an unspecified “grande princesse.” Because everyone’s favorite Enlightenment philosopher wrote twenty-six years before Marie lost her head, and a good several before she ever arrived at Versailles to look down her nose at the rabble, it seems unlikely that she can have inspired Rousseau’s quotation. Abraham Lincoln once observed that “The trouble with quotes on the internet is that you can never know if they are genuine,” and it would seem that his wisdom extends to eighteenth-century print media as well.

Dear Clio,

Why did Martin Luther only bother to nail 95 theses on the door of the cathedral in Wittenberg? I mean why didn’t he shoot for a good round number like a 100? Could he not think of more critical things about the Catholic Church?

Alas, it seems but yesterday that we celebrated Luther’s 400th birthday over bratwurst,  Pilsener and potato salad. In fact it was 1883. That same year, the Prussian Educational Ministry announced their plans to edit Luther’s collected works. That project outlived two German governments and saw completion only a few years ago, in 2009. Today the 119 volumes of the Weimar Edition, as it is called, burden library shelves and intimidate aspiring Reformation historians everywhere. Given such tremendous output, is it possible to wish for more – even five theses more – from Luther’s pen? Apparently it is. Luther posted only 95 theses on the efficacy of indulgences, because he had only 95 things to say. Luther was the sort of writer who knew when he had reached the end. This is a crucial, simple, and yet surprisingly elusive skill for aspiring authors, including History majors. We would all be well advised to understand the extent of our argument, and to stop writing when we have said all that is necessary. Otherwise your professor will suffer from indigestion. Vigorous debate rages over whether Luther actually posted his theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg. It seems that he may have just handed out pamphlets to the curious among the faithful. Before you book tickets to Wittenberg to settle this debate via a forensic examination for nail holes, you should know that the door in question was lost to fire in 1760. In the nineteenth century, King Frederick William IV of Prussia had a replacement forged in bronze, with Luther’s theses stamped onto its outer surface. Whether Luther ever pasted his theses to the door of the church at Wittenberg, they reside there now. Unfortunately, since the door became a monument, very few people ever seem to pass in or out of it, and in fact I have never even seen it opened.

Pilsener and potato salad. In fact it was 1883. That same year, the Prussian Educational Ministry announced their plans to edit Luther’s collected works. That project outlived two German governments and saw completion only a few years ago, in 2009. Today the 119 volumes of the Weimar Edition, as it is called, burden library shelves and intimidate aspiring Reformation historians everywhere. Given such tremendous output, is it possible to wish for more – even five theses more – from Luther’s pen? Apparently it is. Luther posted only 95 theses on the efficacy of indulgences, because he had only 95 things to say. Luther was the sort of writer who knew when he had reached the end. This is a crucial, simple, and yet surprisingly elusive skill for aspiring authors, including History majors. We would all be well advised to understand the extent of our argument, and to stop writing when we have said all that is necessary. Otherwise your professor will suffer from indigestion. Vigorous debate rages over whether Luther actually posted his theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg. It seems that he may have just handed out pamphlets to the curious among the faithful. Before you book tickets to Wittenberg to settle this debate via a forensic examination for nail holes, you should know that the door in question was lost to fire in 1760. In the nineteenth century, King Frederick William IV of Prussia had a replacement forged in bronze, with Luther’s theses stamped onto its outer surface. Whether Luther ever pasted his theses to the door of the church at Wittenberg, they reside there now. Unfortunately, since the door became a monument, very few people ever seem to pass in or out of it, and in fact I have never even seen it opened.

Dear Clio,

Why are the three men who brought Jesus gifts sometimes referred to as “wise men” and sometimes as “three kings”? Were they “wise kings”?

Ye of atrophied source-critical faculties: The Gospel ascribed to Matthew does not specify  the number of Jesus’s generous visitors. It says only that men from the East brought gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Some Christian traditions decided that three gifts meant three men, and in the West they even got names: Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar. Here in this image they are leaning into a stiff breeze. The Greek calls them neither wise men nor kings, only magi. Once upon a time, the word magus indicated the priestly astrologers of the Zoroastrian faith, but by the first century, when the Gospel of Matthew was written, the idea of Zoroastrianism had become exoticized, and the word had come to embrace workers of supernatural wonders more generally, sidling ever closer in definition to our “magician” (an English word that is itself derived from magus) or “sorcerer.” In the Gospel, the magi are clearly astrologers. Thus they follow a mobile celestial object to Jesus’s house and they receive a dream message to avoid the dyspeptic Herod on their return trip to magicland. The magi came to be wise men in the same way that Marie Antoinette’s brioche came to be cake: via translation. Astrology, magic, and Christianity have had a fraught relationship, and English translations of the New Testament since at least King James have hesitated to make astrologers of Jesus’s first houseguests. Curiously, there are other magi in the New Testament. In Acts 8, we meet Simon Magus, who we are told practiced the magical arts and even tried to buy the Holy Spirit, a serious faux pas. And in Acts 13 we read of Elymas, a magus who opposes Paul’s preaching and who was promptly blinded for his trouble. Because neither Simon nor Elymas were every nice, King James and his successors have no trouble calling them sorcerers. As kings, the magi are rather less interesting. Over the centuries, many a reader has decided that Psalms 72:11 – “May all kings fall down before him” – must be a prophetic reference to Jesus. Because the New Testament is rather short on prostrated kings, the magi been pressed into service.

the number of Jesus’s generous visitors. It says only that men from the East brought gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Some Christian traditions decided that three gifts meant three men, and in the West they even got names: Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar. Here in this image they are leaning into a stiff breeze. The Greek calls them neither wise men nor kings, only magi. Once upon a time, the word magus indicated the priestly astrologers of the Zoroastrian faith, but by the first century, when the Gospel of Matthew was written, the idea of Zoroastrianism had become exoticized, and the word had come to embrace workers of supernatural wonders more generally, sidling ever closer in definition to our “magician” (an English word that is itself derived from magus) or “sorcerer.” In the Gospel, the magi are clearly astrologers. Thus they follow a mobile celestial object to Jesus’s house and they receive a dream message to avoid the dyspeptic Herod on their return trip to magicland. The magi came to be wise men in the same way that Marie Antoinette’s brioche came to be cake: via translation. Astrology, magic, and Christianity have had a fraught relationship, and English translations of the New Testament since at least King James have hesitated to make astrologers of Jesus’s first houseguests. Curiously, there are other magi in the New Testament. In Acts 8, we meet Simon Magus, who we are told practiced the magical arts and even tried to buy the Holy Spirit, a serious faux pas. And in Acts 13 we read of Elymas, a magus who opposes Paul’s preaching and who was promptly blinded for his trouble. Because neither Simon nor Elymas were every nice, King James and his successors have no trouble calling them sorcerers. As kings, the magi are rather less interesting. Over the centuries, many a reader has decided that Psalms 72:11 – “May all kings fall down before him” – must be a prophetic reference to Jesus. Because the New Testament is rather short on prostrated kings, the magi been pressed into service.

Dear Clio,

I can’t decide between being a History major and a Political Science major. Why does my history professor keep insisting that I should major in History?

If you want to experience the breadth and depth of an ancient discipline, and ply arts that have been cultivated over thousands of years, then maybe History is for you. If you are up to the challenge of understanding and thinking through legal, social and cultural systems radically removed from our own in time and place, then maybe History is for you. If you want to be the sort of person who understands how things came to be the way they are, the sort of person who, on a vacation to Europe, can explain how the Lateran Obelisk got from the Karnak temple complex to Rome, or the sort of person who, on Patriots’ Day, can explain to her interlocutors why the Boston marathon matters and why it is precisely 26.2 miles long, then perhaps History is for you. If you want to appreciate the contingency and ephemerality of the present, with the perspective to know how very different everything was just a few generations ago, then maybe History is for you. If you cannot get enough of the current election cycle, prefer newspapers to books, and are happy with a field whose Wikipedia page is an utter and ongoing catastrophe (hint: Nicoló Machiavelli did not found any of the social sciences), then by all means sally forth into other endeavors.

Dear Clio,

Did the ancients floss?

Probably nobody has ever flossed.

In the Chapin Corner

by Gretchen Long

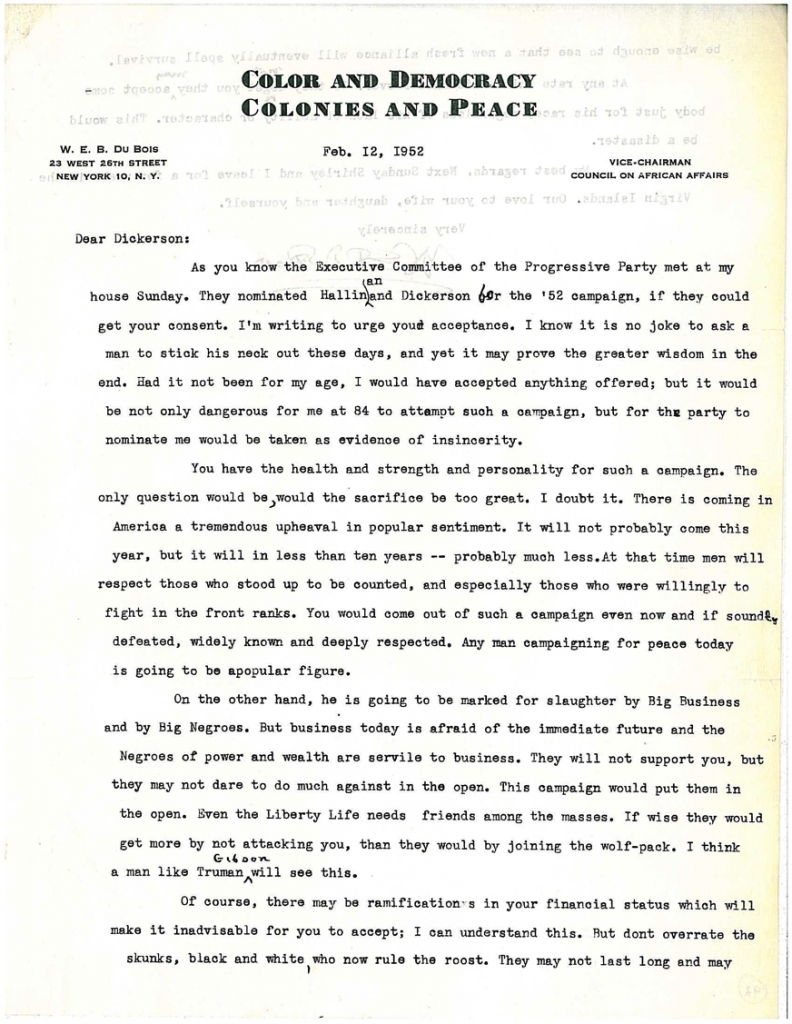

“I know it is no joke to ask a man to stick his neck out these days.”

W.E.B. DuBois from his letter to Earl Dickerson, 1952.

Letter found in Williams College Chapin Library

In this election year, let’s have a look at an original letter written by W.E.B. DuBois to Earl Dickerson of Chicago, recently acquired by the Chapin Library. The letter typed by DuBois – and his relationship with Dickerson – can lead us into a world of African American law, activism, and art. I found evidence of all of this in the Chapin.

In DuBois’ letter, dated February 12, 1952, he reaches out to African American Chicago attorney, Earl Dickerson, urging him to accept a nomination as Vice President on the Progressive Party ticket. DuBois’s letter acknowledges the unlikelihood that Dickerson, who had a successful career at a Black owned insurance company, would leave his job and devote the next eight months to a campaign that the Progressive Party had virtually no chance of winning. Dickerson turned them down and the Republican Eisenhower/Nixon ticket won easily in November of ’52, beating Illinois Democrat Adlai Stevenson.

DuBois reminds Dickerson not to “overrate the skunks, black and white, who now rule the roost.” He feared that if Dickerson refused to run, the party would appoint “some body just for his race, regardless of his lack of ability or character. This would be a disaster.”

At the time he wrote the letter, DuBois’s passport had been confiscated as a result of his run-ins with the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. He would not regain it until 1958 and two years later would leave the US for good. In 1952, however, the letter reveals that W.E.B. DuBois was involved in leftist US politics during the first decade of the Cold War, at a time when European powers still ruled most African nations and fears of Communism and radicalism in the US constrained the work of activists.

The Mississippi born Dickerson was the first African American Alderman (Chicago’s equivalent to City Councilman) to serve in Chicago, and his election was a remarkable accomplishment in 1939. In 1940, he argued a significant case before the Supreme Court, Lee vs. Hansberry, in which he attacked “restrictive covenants” – essentially sets of real estate laws and regulations, as well as private neighborhood group – designed to prohibit African Americans from buying property in designated neighborhoods and subdivisions. Historians point to these restrictive covenants, which operated in the bureaucratic world of mortgage companies, banks, and real estate development, as a major engine of racial segregation and inequality in Northern Cities.

Dickerson’s client in the Supreme Court case was Carl Augustus Hansberry, who had a young, ten year old daughter in 1940, Lorraine Hansberry. Lorraine grew up to be a playwright, an activist, and an early supporter of what we now call LBGTQ rights. Her family’s case, concerning the property her father had purchased in Chicago and the restrictive covenants they confronted, provided material for her writing. Years later in her play, Raisin in the Sun (the 1961 film version with Sidney Poitier is a winner), a black Chicago family runs up against a “neighborhood association” trying to keep them out of the area where they have just bought a house.

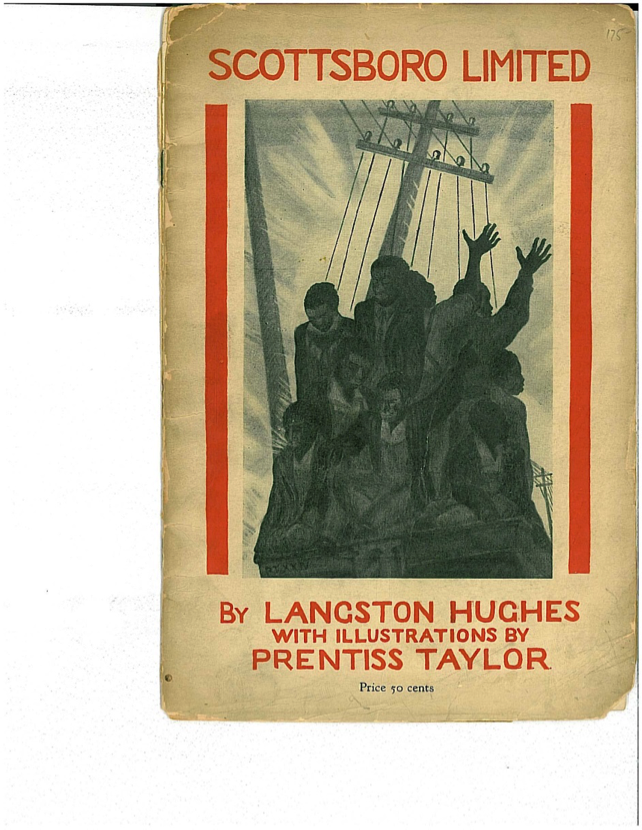

Lorraine’s title for the play came from a poem, “Dream Deferred,” by the African American poet, activist, and ally of DuBois, Langston Hughes. The Chapin Library owns a number of Langston Hughes related objects. My favorite is a signed copy of the Scottsboro Limited, Four Poems And A Play In Verse By Langston Hughes. Published in 1932, the Chapin’s copy is inscribed “For Arthur, belatedly, August 25, 1966” in green ink in Langston’s loopy handwriting. The poems and art focus on the Scottsboro boys, eight young black men accused of raping two white women in Alabama. The case has its own fascinating history, involving the Communist Party in America, activism, violence, and exposure of the danger of all white juries.

The Chapin Library and the college archives are full of surprises and beautiful objects. Make it your business to get in there soon.

Internships for History Majors

There are a good number of History and History-related summer and year-long internships around the nation that are available for History majors. Internships offer valuable hands-on experience doing the work of history and give you a chance to explore some of the careers available in the field. There are many opportunities to work in museums, historic sites and parks, and nonprofit educational and media organizations. Think about the kinds of positions that interest you most – options including positions working directly with the public as a tour guide, interpreter, or public educator; doing behind-the-scenes work as a researcher, interviewer, or as a conservationist; or supporting a history organization through fundraising, curriculum development, or programming support. The following organizations customarily offer summer internships; most are volunteer positions but some are paid and/or offer free housing. Some of these sites are umbrella groups that list internships in many different organizations.

American Association for State and Local History (listings of various jobs and internships):

http://jobs.aaslh.org/jobs

Civil War Trust:

http://www.idealist.org/view/internship/g2cMDJP67ccp/

Faith and John Meem Preservation Trades Internship (Santa Fe, NM):

http://www.historicsantafe.org/Internship.html

HistPress.com (internship opportunities in historical preservation):

http://histpres.com/opportunities/

Martha’s Vineyard Museum:

http://mvmuseum.org/internpositions.php

Massachusetts Cultural Council (Hire Culture: database of various internships and jobs in MA):

http://www.hireculture.org/findjob.aspx

National Council on Foreign Relations:

http://www.idealist.org/view/internship/pMsHnSJz6N2D/

National Council on Public History:

http://ncph.org/cms/careers-training/

National History Center:

http://nationalhistorycenter.org/resources/the-national-history-center-internship-program/

National Park Service Internship Program:

http://www.nps.gov/tps/education/internships.htm

National Park Service Heritage Documentation Program:

http://www.nps.gov/hdp/jobs/HDPEmployment2015.pdf

National Trust for Historic Preservation:

http://www.preservationnation.org/

New England Museum Association (internship and volunteer portal):

http://www.nemanet.org/resources/career-center/internships/

Smithsonian Museums:

http://www.smithsonianofi.com/internship-opportunities/

Internships are also available at many living history sites (ie Colonial Williamsburg and Hancock Shaker Village) and notable museums (including smaller museums like Hull House in Chicago or the Lower East Side Tenement Museum in New York), as well as at the various presidential libraries, state humanities councils, and local history societies. Also consider educational and media organizations that work with history teachers or develop and disseminate digital content to deepen public education, including public television stations; nonprofits like Facing History and Ourselves or the Jewish Women’s History Archive (both based in Boston), and professional organizations such as the American Historical Association and National History Day. This coming summer we will be updating and expanding this list and making it a permanent part of the Department of History’s website. For further information about many of these organizations, please contact Professors Leslie Brown or Annie Valk.

Careers for Historians

What do you do with your History major? Each issue of the Department’s newsletter will contain information about the career patterns of former Williams students who have graduated with a BA in History, listings of various guides to careers for historians, or will reprint articles about job opportunities for recent graduates with a BA in History. In this edition of the newsletter we reprint a recent article published by the American Historical Association..

Entering the Job Market with a BA in History

(from the AHA Today Blog, May 12, 2015)

by Loren Collins

In the last 10 days I met with three history majors in my office to develop strategies for building their careers. The first student wanted to work in the Los Angeles area in some form of museum, archive, or historical site. The second wanted to teach history but prior to entering a credential program wanted to experience the world by teaching English abroad. The third student didn’t have a firm career goal but was leaning toward business: sales or marketing. The advice for each of these students did not change based on their target careers: learn to market what you’ve learned and earned, explore where you want to be, and target the employers you want to work for and approach them before they are approached by someone else who wants your job.

In You Majored in What, a must-read book for any job-hunting liberal arts major, Katherine Brooks addresses the question all history majors receive: “What are you going to do with that degree?” In any economy, but especially in a constricted one like we’ve seen these last few years, people begin to expect and hope for a very linear path from your education to your career. When history majors are asked about their career plans, the person asking is likely waiting to hear “teacher,” “pre-law,” or maybe “government.” As Brooks points out, however, the stats, numbers, and design of a humanities education should allow you to answer, “I’m going to do whatever I want.”

History degrees are versatile, viable, and valuable, but so often they are not understood or marketed on these terms. You may have chosen history because you had visions of devouring

stacks of ancient primary source documents in a glorious repository in an ancient European

metropolis. Or maybe you dreamt of standing in front of a high school class much like your

own high school history class, waking the heart of a high school student a lot like you once were. Or, like many of us, you simply chose the major because you liked it and you knew you’d

have to figure out a job down the road. Whatever your motivation, the first thing you need to learn is how to market your degree.

History is dynamic, and you should be a bright, capable, and thorough thinker, writer, communicator, and researcher because of your time as an undergraduate. The problem is that no one will know it until you tell them! People make assumptions about various majors all the time, and in the news they often recite and rehash false stories about college education that go unchallenged. On your resume, in your cover letter, and during interviews and networking scenarios you need to quantify your experience in terms employers can understand and change the common perceptions out there. Your ability to do this can make all the difference. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, employers cite the following as the top skills employers look for in college graduates:

• Communication

• Teamwork

• Making decisions/solving problems

• Planning, organizing, and prioritizing

• Obtaining and processing information

• Analyzing quantitative data

• Technical skills related to the job

• Using computer software

• Creating and editing written reports

• Selling/influencing others

With a degree in history and all that comes along with being a graduate from a four-year university in our day and age, you should feel confident putting your education and your experience in this kind of language for employers to understand.

After learning to market yourself you need to explore the field. Where do you want to work? Some of us know immediately, while others of us are figuring it out as we go. Search a variety of job ad sources, and interview people in the fields you are interested in. You’d be surprised how quickly people will agree to talk to you for 15–20 minutes about their profession. Explore careers with a career assessment at your college’s career center. Ideally, if you are reading this a year or two before graduation, get some hours in somewhere that will give you knowledge in the field that interests you. Many businesses, libraries, and museums offer part-time jobs or internships. If you want to work in politics, volunteer on election day, join a campaign, or get involved in student government. If you are considering graduate school, spend time with your faculty, ask if you can assist in their research, TA for a class, or become a tutor.

Lastly, once you are nearing graduation you need to think about where you want to live and begin to target the right employers. Find the four or five ad sources for jobs in that area, take a tour through the ads, and get a feel for what is out there. More importantly, make a list of all the places in the area you want to work. If you want to work in a museum, then list all the museums in that location; the American Alliance of Museums is a great place to start. Then go talk to them one-by-one until a position opens up. Visit them every couple weeks to maintain the connection; make sure they know you want to work there more than anyone else. An informational interview here can give you the kind of foot in the door you are dreaming of. If it’s business—say, advertising or insurance—hit all the agencies in town. If it’s politics, list every representative, every party office, and every campaign headquarters that you are willing to work for. The reason this is the make-or-break of how closely you hit the target for your dream job is the fact that only 20% of all jobs out there will ever make it into an advertisement; someone is knocking at the door at the right time before the ad goes up.

My bachelor’s degree is in history. In my senior year, Professor Anne Paulet told our class to make sure employers knew that our degrees meant that we could read, write, and communicate better than almost anybody. I’ve taken that advice and it’s shaped the kind of career adviser to liberal arts students I have become and the quality of job seeker I became. Know how to market your excellent education, explore where you want to put it to use, and talk to all the right employers before they ask for it. It will make all the difference in finding the job you want.

Sources

Brooks, Katherine S. Connecting Students to Careers: Training and Instruction Guide. Sacramento, CA: California Community College Chancellor’s Office, 2010–11.

———. You Majored in What? Mapping Your Path from Chaos to Career. New York: Viking, 2009.

Dickler, Jessica. “The Hidden Job Market.” CNNMoney. http://money.cnn.com/2009/06/09/news/economy/hidden_jobs/.

National Association of Colleges and Employers, “Job Outlook 2015.” Bethlehem, PA: NACE, 2015.

Loren Collins is a career adviser at Humboldt State University working on integrating career curricula into liberal arts coursework. He has a credential in career development, a BA in history and is earning a graduate degree in sociology, both from Humboldt State University. He avidly claims that his degree in history was excellent preparation for all these endeavors.

(Reprinted with permission from the American Historical Association. See the AHA’s BA in History blog series: http://blog.historians.org/category/jobs-and-careers/what-to-do-with-a-ba-in-history/).